‘You get thrown out once they no longer need you’: Tunisian doctor in France threatened with deportation

After arriving in France in 2018, Inès M., a pediatrician, took on numerous positions at a hospital in Val-d’Oise, in particular during the COVID-19 crisis. In February she received an Obligation to leave French territory (OQTF). Speaking with InfoMigrants she expressed her incomprehension over the administrative decision.

One morning in late April, Inès M.* did not go to the Val-d’Oise hospital where she had worked for five years. The 36-year-old Tunisian pediatrician was on sick leave.

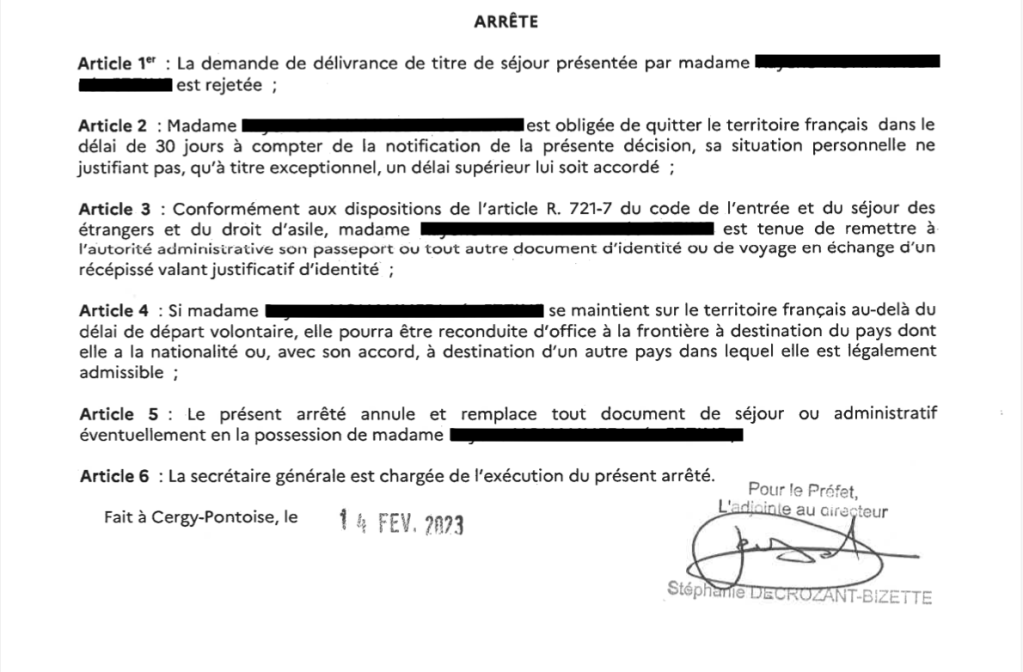

In reality, Inès M. was not ill but served with an Obligation de quitter le territoire français, ‘an obligation to leave France’ (OQTF).

She received the document on February 15 at her home, after the Val-d’Oise prefecture (department, not far from Paris) refused her last application for a residence permit. Since then, she hired the services of a lawyer to challenge the decision, which she considers unfair.

Since February 27, Inès no longer had any papers to present in the event of a police check. “I’m scared when I move around, even though I haven’t done anything wrong”, said the doctor, in tears.

“I no longer go to shopping centers. I make a detour on my way to work, and I feel ashamed when I think about my colleagues finding out. I think about it all the time, it prevents me from sleeping.”

‘For me, the OQTF does not make sense’

For her lawyer, Alexis Tordo, the prefecture’s decision is an aberration.

Inès M. arrived in France in May 2018 after completing her medical doctorate in Sousse, Tunisia. She took on numerous internship positions associated with the Val-d’Oise hospital, paid €1,400 each month, in hope of obtaining recognition of her foreign diploma.

“I arrived to do an internship in pediatrics. I wanted to gain experience and I won’t hide the fact that the political instability in Tunisia and economic pressure pushed me to stay in France,” she said in perfect French. She was even promised employment in the rheumatology department on the provision of the renewal of her residence permit. The project has since fallen through.

In November 2022, Inès M. also married her partner, a mechanical engineer who holds a 10-year residence permit, which makes her eligible for the “private and family life” residence permit.

The prefecture seems to have ignored this element: “For me, the OQTF does not make sense,” said Tordo. “The decision is not legitimate since my client fulfills all the conditions to have the temporary residence permit, because of the regularity of the situation of her spouse, and the stability of her financial situation […] There is no valid reason which could justify the obligation to leave the territory.”

On the front line during Covid-19

For the few thousand foreign doctors called practitioners with a diploma outside the European Union (PADHUE) like Inès M., who work in France, obtaining recognition of their foreign diploma and a license to practice is an obstacle course.

First, they must complete several years of contracts with a precarious status, then pass an international competition with limited places (EVC) and finally a two-year course to consolidate their skills, before obtaining the right to register with the Order of Physicians and access tenured positions.

For most practitioners who have already completed long years of studies, the process of obtaining recognition for their foreign diplomas requires additional schooling. Especially since Covid-19 delayed everything. For two years, foreign doctors filled vacancies in French hospitals, as Inès M. recounts.

“I worked in pediatrics, adult emergencies, general-purpose geriatrics and adolescent psychiatry. In adult emergencies, two-thirds of us were foreign doctors. The truth needs to come out: during the crisis, many French doctors went to infectious disease departments to study the virus, but during this time, foreigners were on the front line! [… ] You are thrown out once they no longer need you.”

By establishing a state of health emergency, the government allowed hospitals to extend the duration of the contracts of associate trainees (initially limited to 2 years). Inès M. remembers a particularly trying period: “We did 8 to 10 shifts a month. We saw 30-year-olds dying every day and we could not go out. I didn’t see my parents for two years !”

Also read: Germany examines ‘offshore’ asylum procedures

Foreign doctors threatened with deportation

In August 2020, the Ministry of Health passed a decree to regularize foreign doctors, known as the Stock law. The decree requires a practioner to have worked in a French hospital for two years between January 2015 and June 2021, but also to have completed at least one day of service between October 1, 2018 and June 30, 2019 (a detail that excludes the many foreign doctors who came to help during the health crisis).

Nearly 4,500 applications, including that of Inès M., were submitted, but three years later, it is clear that the promises have not all been kept.

“We told ourselves to be patient and that we had to follow the procedure. I submitted my file to the Regional Health Agency on October 30, 2020. I met all the criteria for regularization but I still have not had an answer. I have not gone on vacation for two years in order not to miss any notifications. How do you want to live peacefully in these conditions?”, said Inès M.

Also read: Caritas calls for structural assistance on poverty and migrants

‘I am disappointed and angry’

On May 31, 2022, President Emmanuel Macron tasked his Minister of Health François Braun with a “flash” mission to save the overburdened emergency services of French hospitals.

In his report published in June, the minister was concerned about the fate of the 4,000 PADHUE who should “leave the country if their file is not quickly processed” despite being “essential to the functioning of hospitals”.

He had therefore called on the authorities to “simplify and speed up the procedure” as well as to “deviate from the deadline to keep these professionals in their jobs.”

Already delayed twice, the Stock law must officially end on April 30. Inès M. no longer believes in it:

“I am disappointed and angry with myself, because I was naive to think that I had a future here, she notes. Now I don’t know how to make myself heard.” According to her lawyer, the administrative court should render a decision on the situation of Inès M. within two months.

*The first name has been changed at the request of the person concerned.

Also read: In Mayotte, ‘we live in fear of being deported’

For all the latest Health News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.