Why compositions are the soul of Carnatic music?

| Photo Credit: Illustration by Keshav.

If you imagine a Carnatic performance as a piece of ornamental jewellery, then the individual stones and links are the myriad compositions that the vaggeyakaras have painstakingly created. The artistes’ creation (manodharma) forms the design that makes up the ornament. This distinctive combination, therefore, places equal, if not more, emphasis on the compositions.

Muthuswami Dikshitar.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

Many listeners identify the music through compositions, and, in fact, derive their raga affiliation knowledge based on that. Not everyone has a clue about the structure of Dwijavanti but will know that Dikshitar’s ‘Akhilandeswari’ is composed in that raga. Over time, audiences have also developed their own repertoire of what they have always heard and liked, and, therefore, look forward to hearing them again. Artistes’ favourites are plugged into this equation. That is the genesis of ‘song requests’. For many, compositions are the anchor for listening.

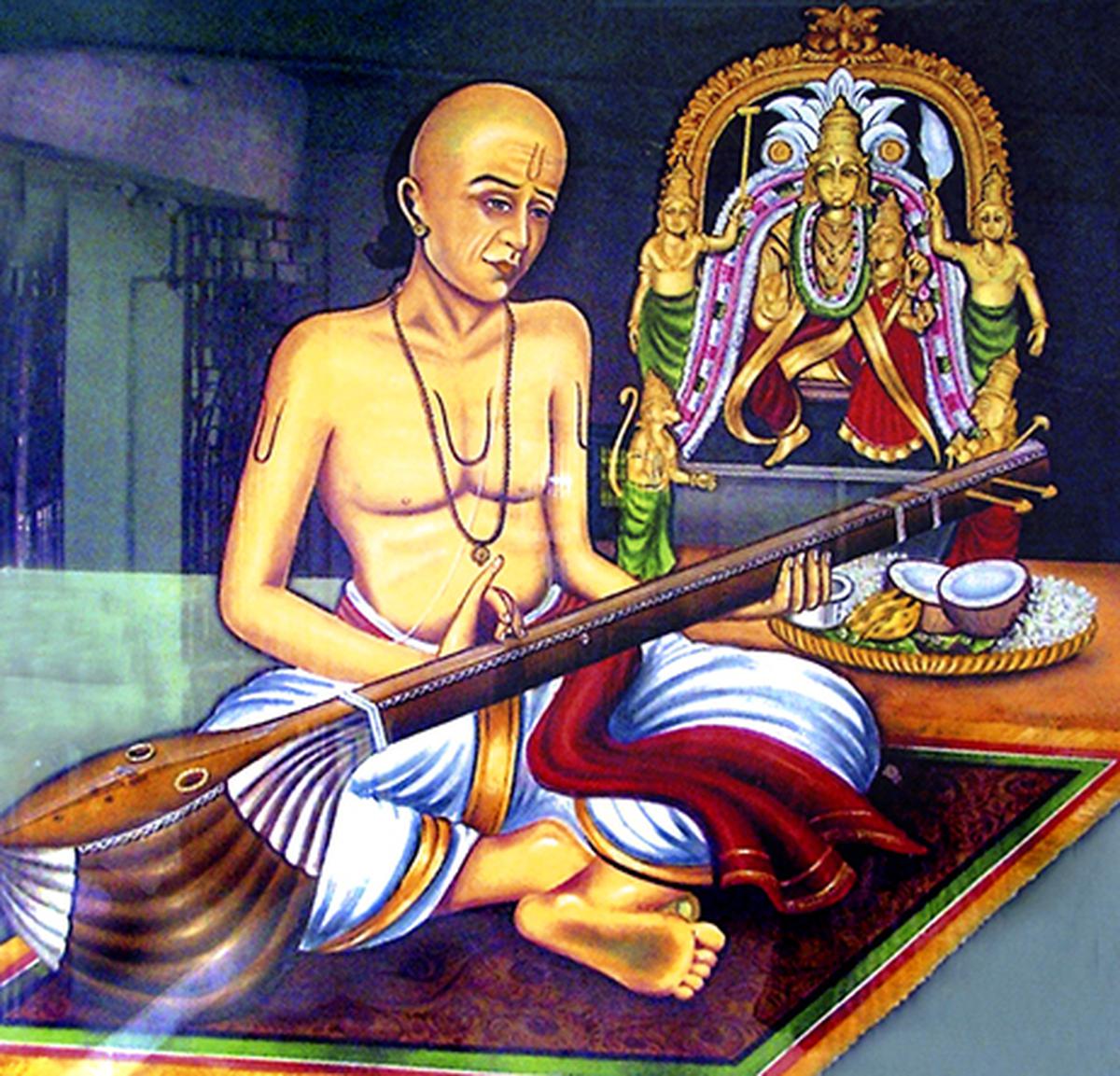

A portrait of Saint-composer Tyagaraja.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

Given such a powerful draw for compositions, we need to dwell on what is the respect with which such gems are handled, especially in the current context. Carnatic music is also unique in another sense that the compositions are generally expected to be sung in the standard structure and even tempo. One has heard ‘Sri subrahmanyaya namaste’ by Dikshitar (Kamboji) or ‘Enduku peddala’ by Tyagaraja (Sankarabharanam) sung by many well-known artistes and there is about 90 per cent congruence in the sangathis and key phrases. Such a tight structure is not just based on notations but also on the patanthara traditions passed down over centuries. It is also a reflection of the cumulative polish that the gems have been given over the years. That such kritis cannot be further improved is a fact that everyone knows, even if some don’t admit it.

Each composition is characterised by its special aspects such as lyrical beauty, musical stamp and polish, the import of the meaning, the mood of the composer, the historical or locational significance, the tala structure and use of special rhythm pattern, the kalapramanam, the stories of how it was conceived, swarakshara, chittaswaram (if any), the mood conveyed to the listener and, so on.

The rules of singing a composition are not different from Newton’s law or Fourier transform. One can’t tinker with them but work on adjacencies and corollaries. Thus, every composition needs to be dealt with on its own merit and created idiom. Rendering them out of sync with convention or their true values may tantamount to disrespecting them.

Just as how traditional food recipes are the same but the taste varies according to the chef, compositions too are capable of being given a distinctive shade and flavour by the artiste, even with standardised sangathis. So, within certain boundaries, artistes are allowed freedom to add delicate embellishments. Not every artiste understands these boundaries or respects them. In the name of artistic expression, sometimes, too much leeway is taken with compositions. Our concerts have, perhaps, half of the time allocated to manodharma music. I have had conversations with some senior musicians and their explanation is that compositions are nowadays learnt from recorded music and not from a guru. So, what is learnt is less than 100 per cent of a kriti (that includes how not to sing a certain phrase). The incomplete learning leads to fillers and notes that are not consistent with standardised structures. The key is, therefore, to learn every kriti correctly and ideally from a guru who is a patanthara expert — there is then little scope for distortion. In fact, the old doyens discouraged ‘too early’ stage ascension — they wanted young singers to have a strong bank of kritis that were fully learnt and imbibed before they saw the limelight. Now, artistes rush in to learn new kritis quickly. That’s the trigger for incompletely-learnt compositions.

A painting of Syama Sastri.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

If compositions are the gems of the ornament or the heart of our music, it begs the question as to what constitutes a good composition. We are sometimes enamoured by ‘new’ and often unfamiliar compositions in various languages, but seldom stop to analyse how they rank in music weight to the real gems.

There are manodharma competitions. Why not competitions just for compositions that would encourage a concerted approach to learning and mastering them? In such competitions, there should be an emphasis on classicism, nuanced understanding, sangathi clarity, and all other aspects that give a composition its unique life.

Every composition needs to be dealt with on its own merit and created idiom. Rendering them out of sync with convention or their true values may tantamount to disrespecting them

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.