The horrors behind the mining industry that powers your life

Review

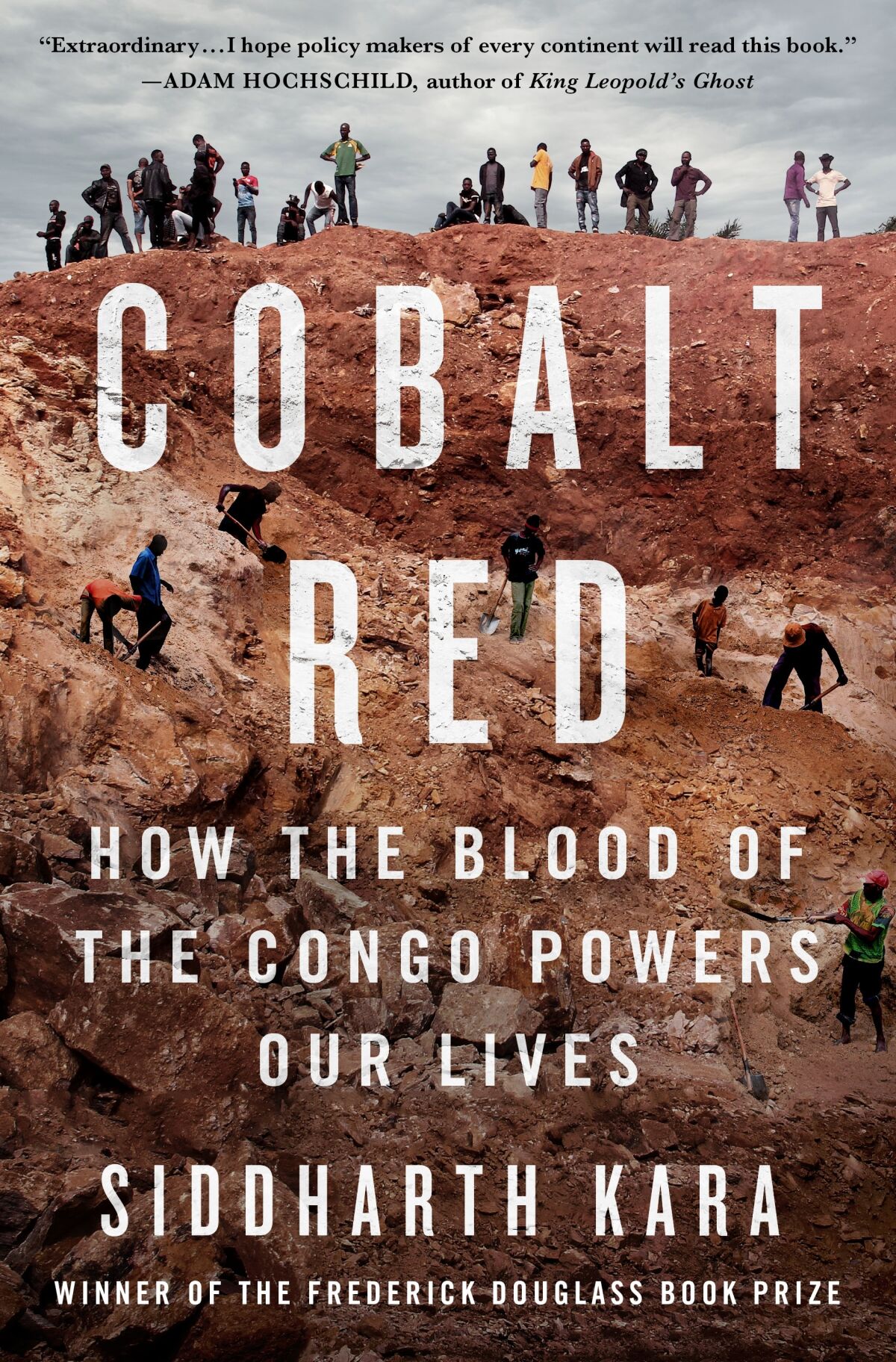

Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives

By Siddharth Kara

St. Martin’s: 288 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

You, the smartphone addict. The modern nomad, lugging your fancy laptop. The electric car driver, smug in your certainty that you’re making the world a better place. Look over here, under this rock; look at what you’d rather not see.

That’s what Siddharth Kara invites you to do in his damning new book, “Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives.” Maybe you already know our booming battery-based economy depends on cobalt mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo. You’ve heard things are bad there. But I’d guess that, like me — smartphone addict, laptop lugger, owner of an electric car — you had no idea just how bad.

Kara’s book is timely, important, compelling, and while the subject is tough his approach is clear and concise and, in that way, easy to read. Anyone who prefers not to put head in sand against the unnecessary human tragedy that accompanies our free-spending lifestyle will benefit from reading this book.

The global economy that provides you your smartwatches, your Teslas and your e-bikes right now requires:

Massive displacement, as homes are cleared, neighborhoods destroyed, millions of trees chopped down to make way for open pit mines.

Toxic dumping that destroys land, crops, animals and fish stocks.

Miners and their families sickened with high levels of cobalt and heavy metals in their urine and blood, cobalt dust in their lungs and — in some zones — yellow sulfuric acid dust caking their bodies and their homes.

Loss of life and limb as narrow mine tunnels, fortified with twisted tree branches if at all, collapse and bury miners alive.

The rape of female miners, who later carry their infant children on their backs as they dig.

Deep poverty on terribly low wages — a dollar or two a day — and debt bondage that leaves miners in a state close to slavery.

Of course, poor people are exploited the world over. What’s remarkable about cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo is that more than half the world’s cobalt in buried there, in a land riven by cruelty and corruption for centuries. And the world’s gotta have it. Today, the vast majority of lithium-ion batteries sold around the world require cobalt. Kara, a former investment banker and now a senior fellow at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, calls it the “blood for cobalt economy.”

Overstated? Not on the evidence presented in the book. “Cobalt Red” is largely anecdotal by necessity, because very little hard data exist on the Congo cobalt supply chain. But the anecdotes are rich and detailed, the product of several years spent inside the Congo at great risk to himself. Congo holds a sizable population of ethnic Indians, and Kara’s Indian background made him less conspicuous than a white traveler would have been.

He still met with obstruction and occasional hostility from militias armed with Kalashnikov rifles, but he carried documents from a few high-placed and cooperative local officials that averted disaster. Sometimes he was permitted inside the mines and sometimes he had to sneak in. There’s been a lot of on-the-ground reporting about the plight of the miners, but journalists tend to visit for short periods of time with managed access, leading to stories that may be hard-hitting but often superficial. Kara goes deep.

The focus is on so-called artisanal miners, known as diggers. That quaint, trendy adjective is misleading. These mines, not directly controlled by any major mining company, turn out lower-grade, hard-to-reach cobalt that may not be worth a big company’s investment.

The diggers scavenge “for whatever scraps they [can] find, like birds picking at bones after the big cats have finished gorging,” Kara writes. One study showed as much as 30% of Congo’s cobalt is sourced from artisanal mines.

Pay these men, women and children a buck or two a day, then mix the mined cobalt into the supply chain, with nary a trace of its hellish origin, and there’s plenty of money to be made — as long as you’re not a digger.

The system traces back to Belgian domination of the Congo, first to extract ivory and then — for the auto industry — rubber. After independence, the exploitation was then taken up by Congolese dictators and kleptocrats with help from the CIA.

Billions of dollars in mining revenue pile up and somehow very little of it trickles down to the population at large. This massive theft, Kara insists, is tolerated by consumer device makers and electric car manufacturers whose main concern is maintaining a cheap and steady supply.

Kara paints unflinching portraits of the people who toil at the bottom of the rechargeable battery supply chain. One is Priscilla, who makes less than the male diggers, eighty cents a day. “Priscilla said that she had no family and lived in a hut of her own,” Kara writes. “Her husband used to work at the site with her, but he died a year ago from a respiratory illness. They tried to have children, but she miscarried twice. ‘I thank God for taking my babies,’ she said. ‘Here it is better not to be born.’”

Siddarth Kera’s ‘Cobalt Red’ unearths the horrific working conditions that fuel our growing dependence on batteries.

(Lynn Savarese)

Priscilla’s meager haul will be sold to middlemen called négotiants who make several times Priscilla’s cut by transporting cobalt in raffia sacks to so-called depots, primarily run by Chinese citizens, who sell it to mining companies.

The people Kara compassionately profiles not only could never afford to buy a smartphone, they are shocked to find that almost everyone in the United States has electricity and running water in their homes.

The tech and car companies claim they don’t source cobalt from artisanal mines, but Kara repeatedly and consistently sees the stuff entering the supply chain; he calls these claims “fiction.” The companies, he says, hide behind indecipherable legal language to claim their innocence.

Kara doesn’t spend much time evaluating the depth of corporate indifference. To me this seems to be a subject for journalists to further explore. “We would not send the children of Cupertino to scrounge for cobalt in toxic pits, so why is it permissible to send the children of the Congo?” Kara writes.

Researchers are exploring new technologies that could lead to high-density batteries that don’t require cobalt. Kara mentions this, but glancingly. Nor does he mention a cobalt battery alternative used by some automakers, lithium-iron-phosphate, that’s cobalt free but has trade-offs in density and performance.

The fact remains that cobalt batteries will increasingly power the consumer economy for many years to come. Kara’s goal is to shine a light under that rock, so we in the developed world get an honest look at who pays the highest price for our consumer goodies and luxury electric cars.

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.