Review: Photo visionary Imogen Cunningham gets a refocus in new Getty retrospective

Photographing a magnolia blossom, Imogen Cunningham once said, was “the most common job I ever did.”

In the sprawling, illuminating retrospective of her work on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum, the first thorough survey in more than 35 years, it’s easy to see one main reason why that conventional flower is also the subject of one of Cunningham’s most well-known pictures. With “Magnolia Blossom,” the ordinary is made extraordinary.

Cunningham burrowed deep inside. Intimacy unfurls.

The white petals of the flower curl around the tightly bunched cluster of pistils at the center, reaching to all four edges of the print. Those edges separate the exquisitely organized work of art from the ordinarily chaotic world muddling along outside it. The photograph’s edges — the only sharp, straight lines anywhere to be seen — slice off a view that is otherwise a surfeit of graceful curves. The framing boundaries of those sensuous arabesques and organic spirals become like razors.

Magnolia blossoms are rather waxy and light-reflective, but these soften into velvety fans through the glow of filtered illumination Cunningham pulled in from the upper right. Diaphanous, the petals harness light’s visual capacities to appeal to the sense of touch, not just sight. The bundled knot of spiraling pistils recalls the elaborate design of a Javanese Hindu temple.

Cunningham photographed the flower in 1925, and she printed the negative many times in the following years. It appealed, she said, to conservative buyers, many of whom saw it on almost continuous exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

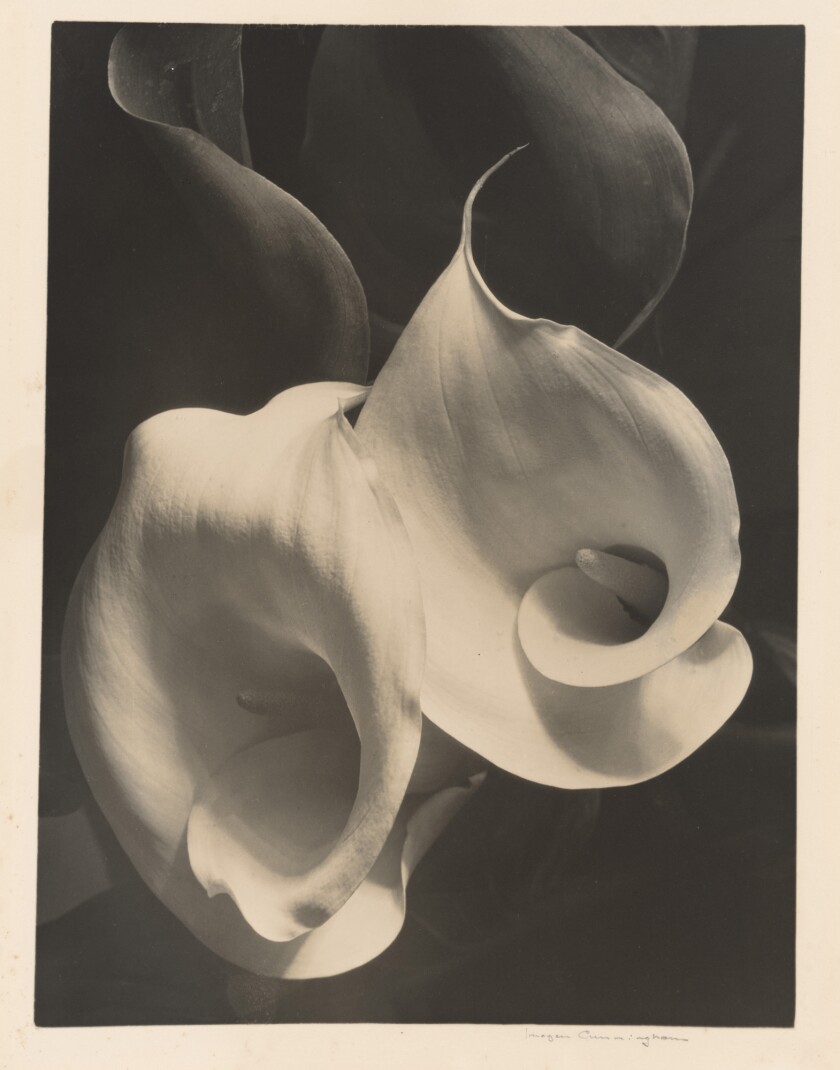

Imogen Cunningham, “Two Callas,” 1925-29, gelatin silver print.

(© Imogen Cunningham Trust)

Conservative or not, those buyers seem to have been responding intuitively to a feature that recurs throughout the nearly seven decades she worked. (Cunningham died in San Francisco in 1976 at age 93.) The warmth, tenderness and closeness — the intimacy — she constructed for the subject is front and center. It stands in sharp contrast to the rising flood of impersonal, stereotyped photographic images that characterize modern commercial culture.

Intimacy characterizes her best portraits, nudes, still lifes, rural and industrial landscapes, street photographs — even an ethereal 1910 view of the iconic fountain in London’s Trafalgar Square. Backlighted by the sun, the tiered fountain of splashing light is a virtual silhouette that fronts the classical base of the famous column to Lord Nelson, hero of a naval victory in the Napoleonic Wars.

The lower third of the composition is all water, as if the artist (and, by extension, the viewer) were wading out in it. Cunningham turned away from the stately, official bombast of the nationally important commemorative site and — pictorially, at least — got her feet wet instead.

That renunciation of — or at least indifference to — officially sanctioned or expected experience seems to me a constant operating guide to her otherwise diverse output. It’s idiosyncratic.

Cunningham was born in Portland, Ore., in 1883, the fifth in a family of 10 children. That same year, composer Richard Wagner died in Venice, Karl Marx died in London and 12 people were trampled to death in New York City when a stampede erupted among people riled by a rumor that the brand-new Brooklyn Bridge, an industrial wonder, was about to collapse. (It didn’t.)

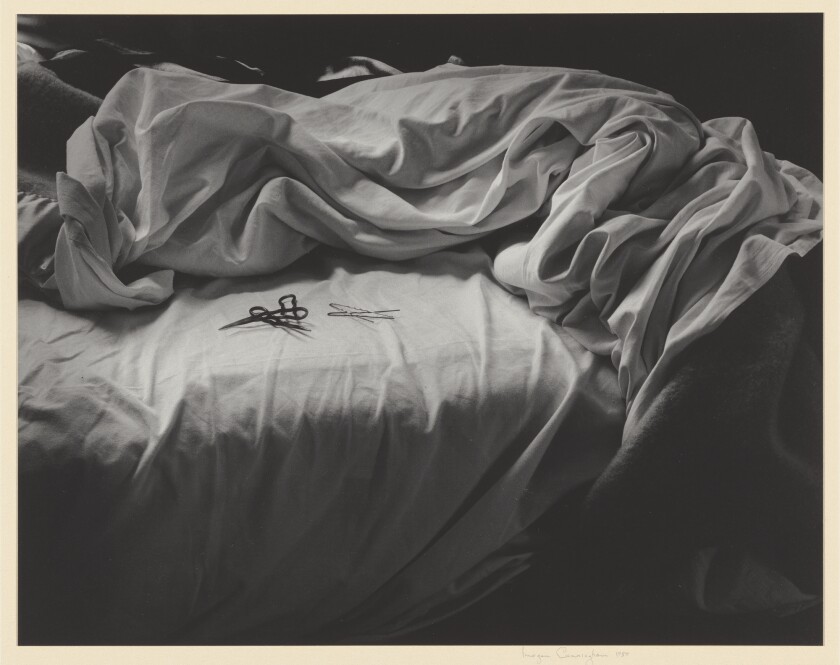

Imogen Cunningham, “The Unmade Bed,” 1957, gelatin silver print.

(© Imogen Cunningham Trust / Getty Museum

)

She grew up in Seattle, far from all that. Her first camera was a mail-order purchase, and when she enrolled at the University of Washington, she studied chemistry, a boon to understanding darkroom printing processes. After graduation, she got a job working for Edwin S. Curtis on the first few of his 20-volume set of photographic portraits, “The North American Indian.”

Cunningham matured into a world where a camera wielded by an artist was still relatively new and, to art’s establishment, controversial. She did travel to Germany to study; but, working on the West Coast — she moved to the Bay Area with her husband, printmaker Roi Partridge, in 1917 — created an unmistakable opportunity for a sizable amount of creative freedom.

Cunningham’s career is usually divided into two phases. First came her association with Pictorialism, in which photographs aspired to a visual relationship with traditional painting. Next is Group f/64, a collective that supported a Modernist vision, which she co-founded in 1932 with Ansel Adams, John Paul Edwards, Sonya Noskowiak, Henry Swift, Willard Van Dyke and Edward Weston.

Composition, surface texture, traditional subject range, obvious manipulation and hand-crafting — Pictorialism prized the making of a picture over merely taking one, which doubters complained was all a camera could ultimately do. Cunningham’s soft-focused portraits and landscapes of the teens and early 1920s are exemplary. (She learned a lot from the work of her early idol, Gertrude Käsebier.) To some extent, Pictorialist photographs emphasize the “work” in a work of art.

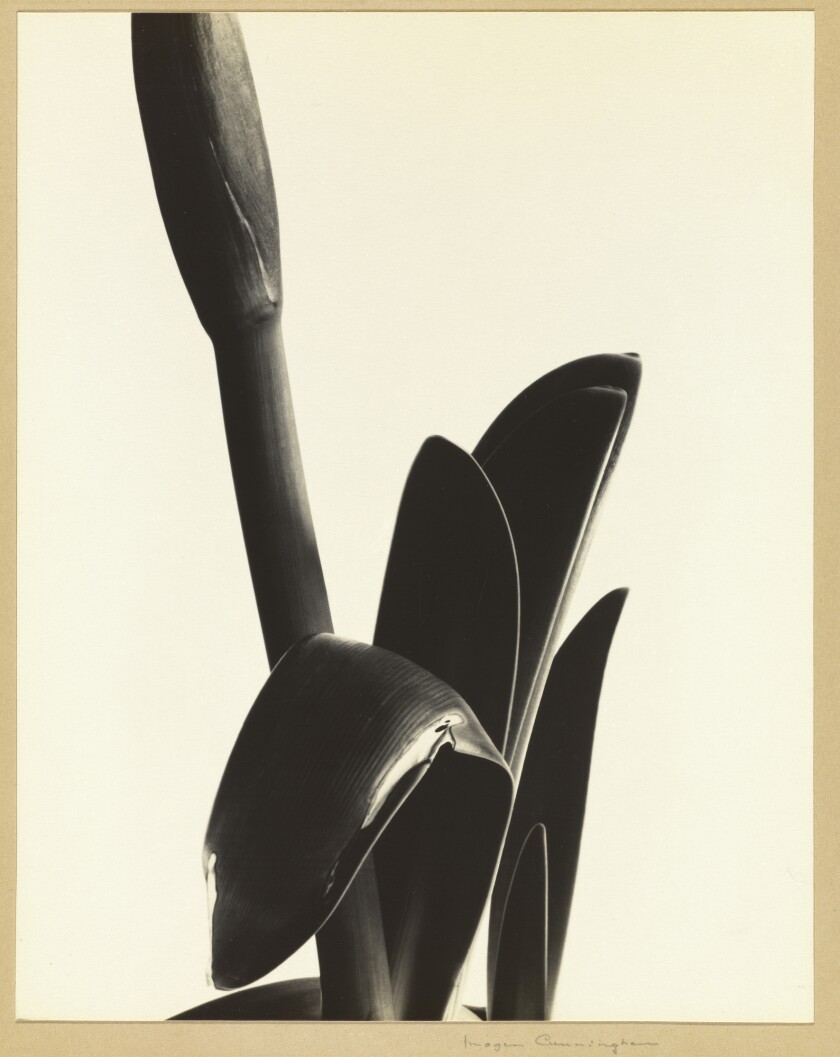

Imogen Cunningham, “Amaryllis,” 1933, gelatin silver print.

(© Imogen Cunningham Trust / Getty Museum)

As Getty curator Paul Martineau notes in the show’s fine catalog, written with photography historian Susan Ehrens, that labor was also appropriate for a woman — and in a particular way. Cunningham’s 1913 essay, “Photography as a Profession for Women,” describes it as “not really a matter of suitability to sex as to individuality.” Her uniqueness as a personality was to be mirrored in the individuality of her portrait subject, which she was obliged to draw out in a photograph.

Artist and sitter met on the plane of the photographic negative and its print, you might say. That’s one way to describe the intimacy embodied in her art.

Group f/64, on the other hand, formalized a direction Cunningham’s work began to take after her move to San Francisco. Now, uniqueness also meant doing what only a photograph could do, as distinguished from painting. Sharply focused and removed from natural context, botanical images of calla lilies, aloe and amaryllis are nearly abstract. A double take is almost essential to identify that the stripe down the middle of one otherwise nearly blank picture is in fact a blade of flax.

Cunningham’s sharp-focused work is her most influential. In her circa 1928 photograph of an empty concrete amphitheater at Mills College, for instance, bands of dark and light curve outward like ripples of water from a pebble dropped in a pond, filling the frame. The luminous ethereality, confounding for slabs of concrete, was repeated a few years later in a similarly composed picture, “The Thinker,” by Los Angeles photographer Hiromu Kira, who added a solitary figure seated on a step, visually carried along by the waves.

The Getty show casts a wide net. Among Cunningham’s most accomplished portraits are those of LGBTQ subjects — a virtual subset of her work, and early for the history of photography.

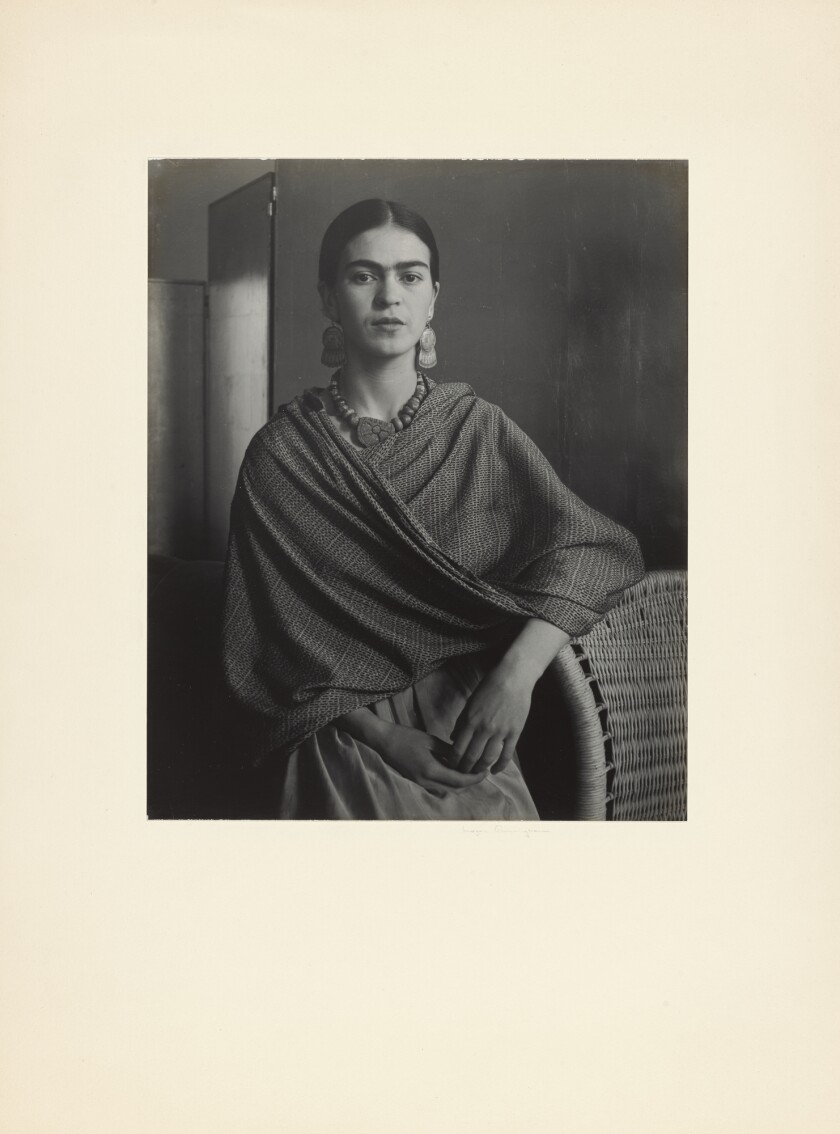

Imogen Cunningham, “Frida Kahlo Rivera,” 1931, gelatin silver print.

(© Imogen Cunningham Trust)

During her long career, she photographed writer Gertrude Stein, potter Laura Andreson, painter Frida Kahlo Rivera, actors Spencer Tracy and Cary Grant, musician Henry Cowell and more. It’s hard to know whether she was conscious of it — gaydar? — but in retrospect, it reflects a feminist understanding that homophobia is an element of the misogyny she herself had faced.

Her riveting 1959 picture of Stan Roy, a twentysomething friend, frames him in a classic, bust-length frontal pose, with light pouring in from one side. The light dramatizes physical materiality, while expanding to its fullest capacity the tonal range of the young man’s black skin. Roy holds his right hand up to cover half his face, striations of light and shadow from unseen window blinds outside the frame creating a diagonal pattern across vertical fingers.

You find yourself looking very closely to read the detailed image, scanning the carefully orchestrated body for any revelation of interior life. Just one eye looks back, the other blocked by his hand.

A gemstone on a ring turned directly toward the camera matches the staring eye adjacent. Thus adorned, the intensely intimate image creates a complex dance of exposure and concealment — unsurprising, yet powerfully suggestive at a time when the civil rights movement was shifting into high gear.

The Getty exhibition represents a major effort at revitalizing interest in the photographer, who was once famous enough to appear as a guest on “The Tonight Show With Johnny Carson,” not long before she died. (He was certainly admiring enough, but Carson was also not above milking the kooky-granny-artist bit for all it was worth. No chump, she gave as good as she got, drawing belly laughs with her retorts.) A smaller survey exhibition, “Seen & Unseen: Photographs by Imogen Cunningham,” has been touring for several years and arrives in May at the Sonoma Valley Museum of Art in Northern California. Together, these shows secure her top tier in the ranks of 20th century photography.

‘Imogen Cunningham: A Retrospective’

Where: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood

When: Through June 12. Closed Mondays

Info: www.getty.edu

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.