Review: Percival Everett rewrites the Southern racial narrative

On the Shelf

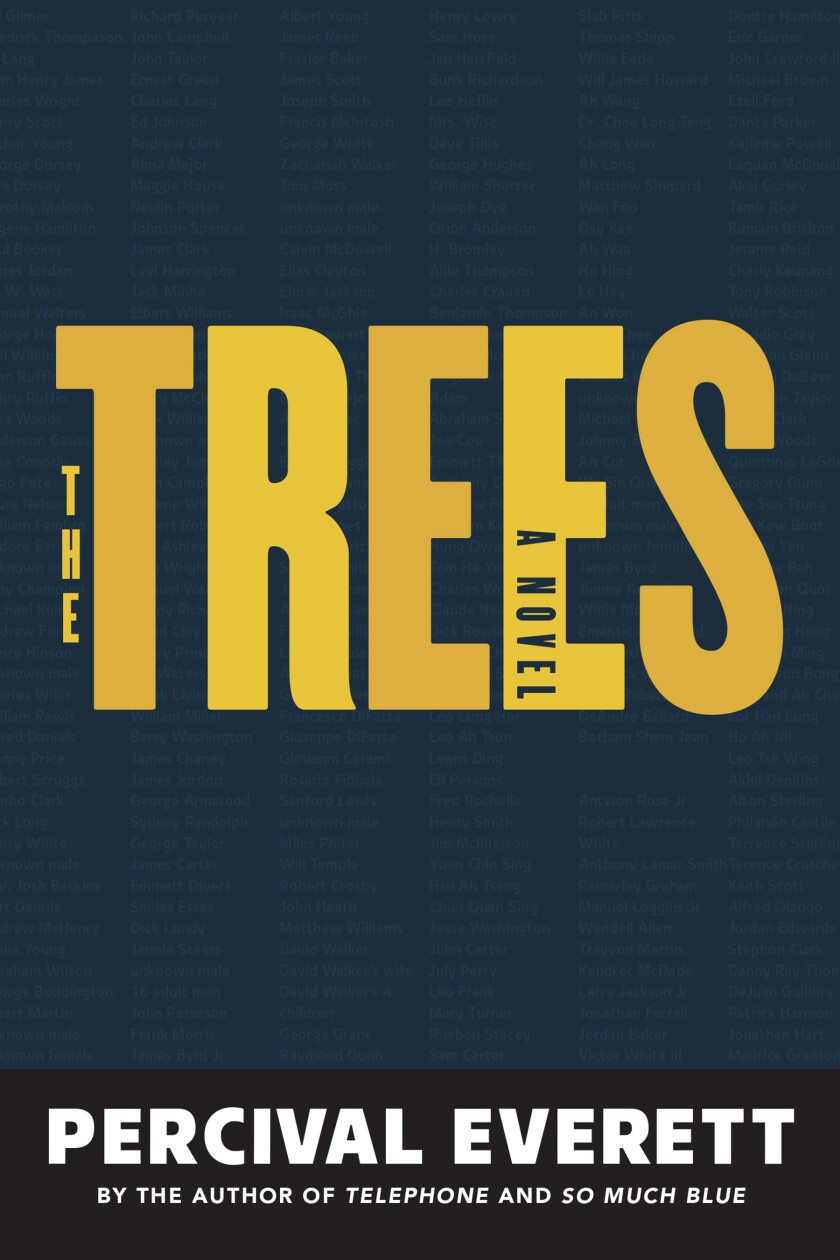

The Trees

By Percival Everett

Graywolf: 288 pages, $16

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“If you want to know a place, you talk to its history,” says Mama Z, one of the characters in Percival Everett’s “The Trees.” Mama Z is the local root doctor in Money, Miss., the setting for much of the novel. It was in Money, in 1955, that 14-year old Emmett Till, a Black boy visiting relatives from Chicago, was kidnapped, tortured, lynched and dumped in the Tallahatchie River. His mother, Mamie Till, insisted on an open casket despite her son’s horrific injuries so the world could see what had been done to her son.

Everett is a USC professor and the acclaimed author of 22 novels, most recently “Telephone,” an experimental novel released in three different versions. In “The Trees” he experiments with history, partly in the character of Mama Z, who has chronicled every single lynching since 1913, the year of her birth (all 7,006 of them). But what he’s really up to is a radical genre game both hilarious and deadly serious.

The novel opens with Everett’s assessment of Money, Miss., which “looks exactly like it sounds. Named in that persistent Southern tradition of irony and with the attendant tradition of nescience, the name becomes slightly sad, a marker of self-conscious ignorance that might as well be embraced because, let’s face it, it isn’t going away.”

The butt of the joke here is the white Establishment, reduced by Everett’s tropes and puns to a redneck laughingstock. The initial focus is on the Bryant family, members of whom were responsible for Till’s death. Their dialogue is rendered in pidgin English, their naming conventions the stuff of slapstick: “Also at the gathering was Granny C’s brother’s youngest boy, Junior Junior. His father, J.W. Milam, was called Junior, and so his son was Junior Junior, never J. Junior, never Junior J., never J.J., but Junior Junior. The older, called Just Junior after the birth of his son, had died of ‘the cancer’ as Granny C called it. …”

In older stories of the South, Black characters are one-dimensional folk, often illiterate, entirely reliant on white largesse or mercy. In “The Trees,” it’s the Black characters who must deal with simple white folk barely distinguishable from brutes. Their Lost Cause, their Virgil Caine tragedies and their “economic anxiety” are erased. They are simply stupid, their violence lacking any rational veneer — never mind their sense of superiority.

The plot is set in motion when Junior Junior Milam is found murdered — mutilated and castrated — alongside the body of a young Black man. Milam is the son-in-law of Granny C, who turns out to be Carolyn Bryant. She was the woman who accused Emmett Till of wolf-whistling at her, which led to Till’s murder.

Jim Davis and Ed Morgan, two Black members of the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation, are sent to aid the white local sheriff in investigating the crime. Then the corpse of the Black man disappears from the morgue, only to show up again when another white man in Money is murdered. Davis and Morgan quickly determine that the victims are descendants of those who murdered Till, and they begin to believe the ghost of Till is taking his revenge.

When a third man is murdered in the same way, this time in Illinois, the FBI sends a special agent over from Atlanta to join the investigation. The three agents are introduced to Mama Z by a local waitress and begin to piece together events. As the murders escalate and make national news, Everett summons horror tropes in service to notions of what justice might look like. And by visiting violence on the descendants of Till’s killers, he examines the notion of collective guilt — the way it festers in the absence of reckoning or reconciliation.

In “The Trees,” Everett’s enormous talent for wordplay — the kind that provokes laughter and the kind that gut-punches — is at its peak. He leans on the language of outrage and hyperbole to provoke reactions a history book could never elicit.

Witness the clarifying contrast between Mama Z and professor Damon Thruff, author of an academic study of racial violence. Mama Z describes his book to him as “scholastic,” which Thruff perceives as insult. “‘Your book is very interesting,’ Mama Z said, ‘because you were able to construct three hundred and seven pages on such a topic without an ounce of outrage.’ Damon was visibly bothered by this. ‘One hopes that dispassionate, scientific work will generate proper outrage.’”

If only that were true. Think of how many books on the Tulsa Race Massacre failed to spark outrage until HBO’s reboot of a comic book, “Watchmen,” finally stimulated mass interest; how “Get Out” and “Lovecraft Country” pricked consciences left unscathed by a century of scholarship.

Everett employs these same genres without apology, but like the best of those shows he also attacks a question that dogs recent criticism. Racism is a horror, a source of personal and collective trauma. Whether horror is the appropriate genre for processing that trauma, even in the service of building empathy, has been the subject of cultural discussion. Can entertainment educate, and can it avoid exploitation?

The history of lynching is inextricable from entertainment. White Americans turned photographs of lynching into postcards, morbid “wish you were here” selfies proving they were witness to the killing of another human being. So why shouldn’t Everett make it into a play within a play, thereby hoping to catch the conscience of the king?

If white readers who live outside the South believe themselves to be “in” on Everett’s joke, they too are in for a surprise. The rash of revenge he unleashes captures those responsible for horrors far beyond the Jim Crow South, eventually implicating virtually all of us.

Everett makes clear that the sins of the fathers fall upon all white Americans — anyone who has benefited from terror, intimidation or systematic repression, regardless of whether they held the rope. He has made some audacious leaps over nearly 40 years of writing, but “The Trees” may be his most audacious. He makes a revenge fantasy into a comic horror masterpiece. He turns narrative stakes into moral stakes and raises them sky-high. Readers will laugh until it hurts.

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

xfbml : true, version : 'v2.9' }); };

(function(d, s, id){ var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) {return;} js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = "https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js"; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); }(document, 'script', 'facebook-jssdk'));

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.