Daniel Roher no longer leads a double life — but 2021 was different. Then, even close friends of the Canadian film-maker had no idea what he was working on. On social media he was mostly silent, save the occasional photograph of his grandmother.

Then, on January 13 this year, an out-of-nowhere press release announced Navalny, a documentary portrait of jailed Russian dissident Alexei Navalny, secretly filmed in Germany over three months from November 2020. It begins with his recovery after having been poisoned with the nerve agent novichok, and ends with his arrest at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport. This, it transpired, was what Roher had been up to.

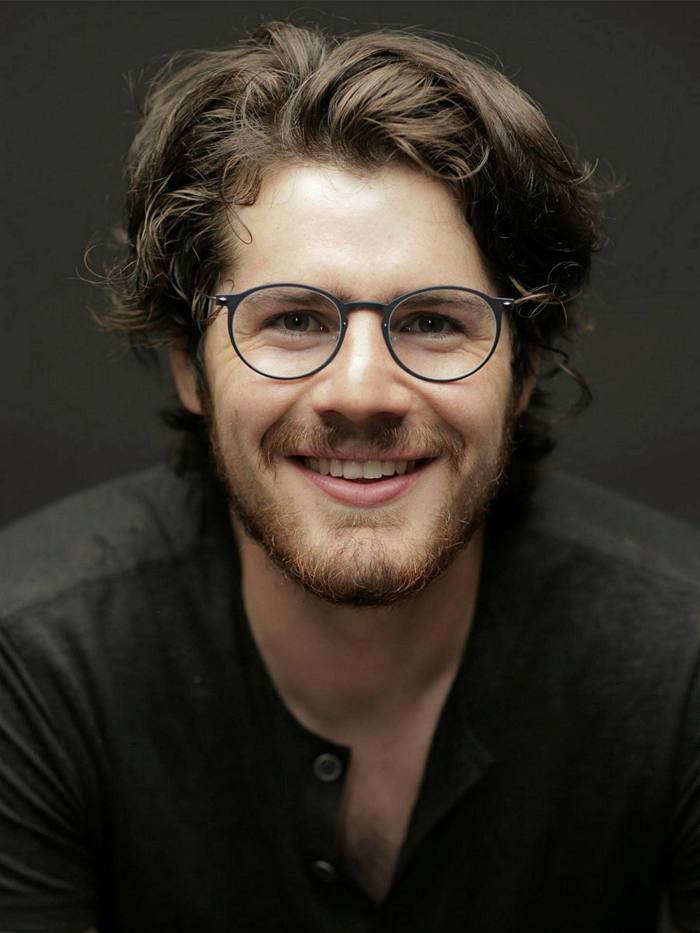

In the past 10 weeks, he has been even more dramatically under the spotlight. Despite the war in Ukraine, the 29-year-old film-maker says Russian state propagandists have still found time to paint him as a CIA pawn. “All I can do is laugh,” he tells me.

Since January, the world has of course changed. A film that would once have pushed for the release of its subject from the notorious IK-2 prison colony now has a dual mission: “The urgent necessity is simply to remind people that there is an alternative Russian future.”

“I was in the right place when I had to be,” Roher says of the moment in 2020 when his film abruptly came together. The previous year, he released Once Were Brothers, a well-regarded documentary about musician Robbie Robertson. But he also wanted to make films with real-world political impact. A potential project had brought him to Vienna, base of Christo Grozev, a Bulgarian researcher for investigative collective Bellingcat. “Sherlock Holmes with a laptop,” Roher calls him. Yet the director was all set to return to Toronto without a film when Grozev told him of a breakthrough. Using open source intelligence, he had identified the Russian FSB agents responsible for trying to kill Navalny.

The pair were soon driving for hours to reach Ibach, a hamlet in the Black Forest where a recuperating Navalny was once more campaigning against the Kremlin. Grozev presented Navalny with his flight manifests and black-market phone metadata. Roher did what directors do: he pitched. “I told Alexei: what is happening is historic and must be recorded. And I’m here. My camera is here.”

While he had only a layman’s knowledge of Russian politics, Roher believes another quality counted in his favour. A wonkish lover of public policy, he might be called militantly civic-minded. (He wants eventually to run for office in Canada.) “And I think that resonated with Navalny. He decided to like me.”

Navalny playfully suggested the Netflix series Tiger King as a model; Roher was not the man for that job. More serious debate concerned the power of veto. “I said, ‘It is absolutely your prerogative just to hire someone to make a film for you. But I can’t give you final cut.’”

Navalny cautiously agreed. Initially, Roher worked without funding. (CNN later provided support.) He focused first on Grozev’s breadcrumb trail of the attempted assassination by the FSB and, by extension, Putin. And he went dark even to old friends: “I understood we needed silence.” His biggest personal anxiety was the security of his camera files, but he recognised still higher stakes in Ibach. “We had to assume the regime might try to murder Alexei again while we were filming.”

If the Kremlin was humiliated by Navalny’s survival, salt would soon be added to the wound. With Grozev having identified the members of the FSB kill team, Navalny proceeded to phone them up (with Roher filming), posing as an FSB bureaucrat, demanding to know how the hit had failed. A hapless chemist named Konstantin Kudryavtsev took the bait, disclosing the whole conspiracy in grimly riveting detail. Navalny’s revenge was served cold and with a hint of farce (much of the plot turned out to involve his underwear.) “It’s just a fabulous performance,” Roher says.

But the film would also widen its lens. Over the next three months, the director took a rolling snapshot of Navalny in exile: liaising with his advisers, playing Call of Duty (his stalwart wife Yulia Navalnaya prefers chess), and creating the YouTube videos whose exposure of vast corruption among Putin’s circle has reached millions of Russians and come to define his opposition. Final cut or not, Roher says he was alive to the risks of working with such a brilliant media strategist. “My job was to be hyper-aware of Alexei as an authentic modern media genius. The question of how much he might be using me is woven into the film.”

Off-camera, Roher says, the pair could have heated conversations about issues such as censorship. (Navalny publicly opposed the banning of Donald Trump from Twitter.) “But Alexei liked that. He relishes the fun of adversarial debate.” The Navalny of his film is as shrewd as any politician — but also witty, charismatic and courageous. We are invited to laugh at Russian state media suggesting that his illness after poisoning was caused by western vices of “orgies and anti-depressants”. Less amusing is that the same propaganda machine cooked up the fraud charges for which he is now jailed.

But not everything negative is a Kremlin smear. Any honest portrait of Navalny must deal with complexity. Although he is now more or less a social democrat, in the 2000s he marched alongside far-right Russian ultranationalists. Roher interrogates those old associations on camera. “It was uncomfortable. The subject is taboo for him. I had to double down when he tried to brush me off.” (Navalny eventually defends his decision as attempted anti-Putin coalition-building.)

In 2019, veteran film-maker Alex Gibney released Citizen K, a study of exiled former oligarch turned pro-democracy activist Mikhail Khodorkovsky. When I interviewed Khodorkovsky back then, he dismissed Navalny as “within the paradigm of the tsar”. Roher disagrees. “A splintered opposition only helps the Kremlin. But also Alexei encourages democratic competition. So what he might say is, ‘Let’s both work so eventually we run against each other.’ And I know Khodorkovsky has been jailed himself, but it’s one thing to criticise in London or Vilnius or Vienna. It’s harder to go back to Russia and be arrested.”

Navalny did exactly that in January 2021. He had always told Roher that he intended to return to Moscow. Still, the director learnt of the timing only minutes before it was announced on social media. There has since been speculation about whether Navalny was gambling on anti-Kremlin protests inspired by his presence kindling an uprising — or making a longer bet on an ageing Putin’s health. “I only know he understood he was facing arrest,” Roher says. “And he felt that was his destiny. But his optimism is real. He believes Putin will fall and he will run for president. And, as a politician, he believes he’ll win.”

Roher last saw Navalny being led away at Sheremetyevo. His task then became to edit his 500 hours of footage discreetly. A year later, the film’s existence was made public. A week after that, a surprise premiere at the Sundance Film Festival brought a standing ovation and what Grozev identified as a quick-fire attack by Russian bots, down-voting the film’s entry on IMDb.com. Despite the acclaim, in the weeks before Ukraine was invaded, not every western film distributor was keen to come onboard. “If you wanted to be in business in Russia, you couldn’t get mixed up with us,” Roher explains. (Navalny is being released in the US by Warner Bros/HBO and in the UK by indie Dogwoof.)

But the film’s western audience is no longer his primary concern. With Russia now lost to a blackout of independent news, subterfuge comes into play again. “Obviously I can’t speak to the detail,” Roher says, “but we plan for the film to be seen inside Russia by as many Russians as possible. That is the number one priority now.”

In Curzon cinemas in the UK from April 12, with a wider release to follow.

In US cinemas from April 11 and coming to HBO Max soon

Follow @ftweekend on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.