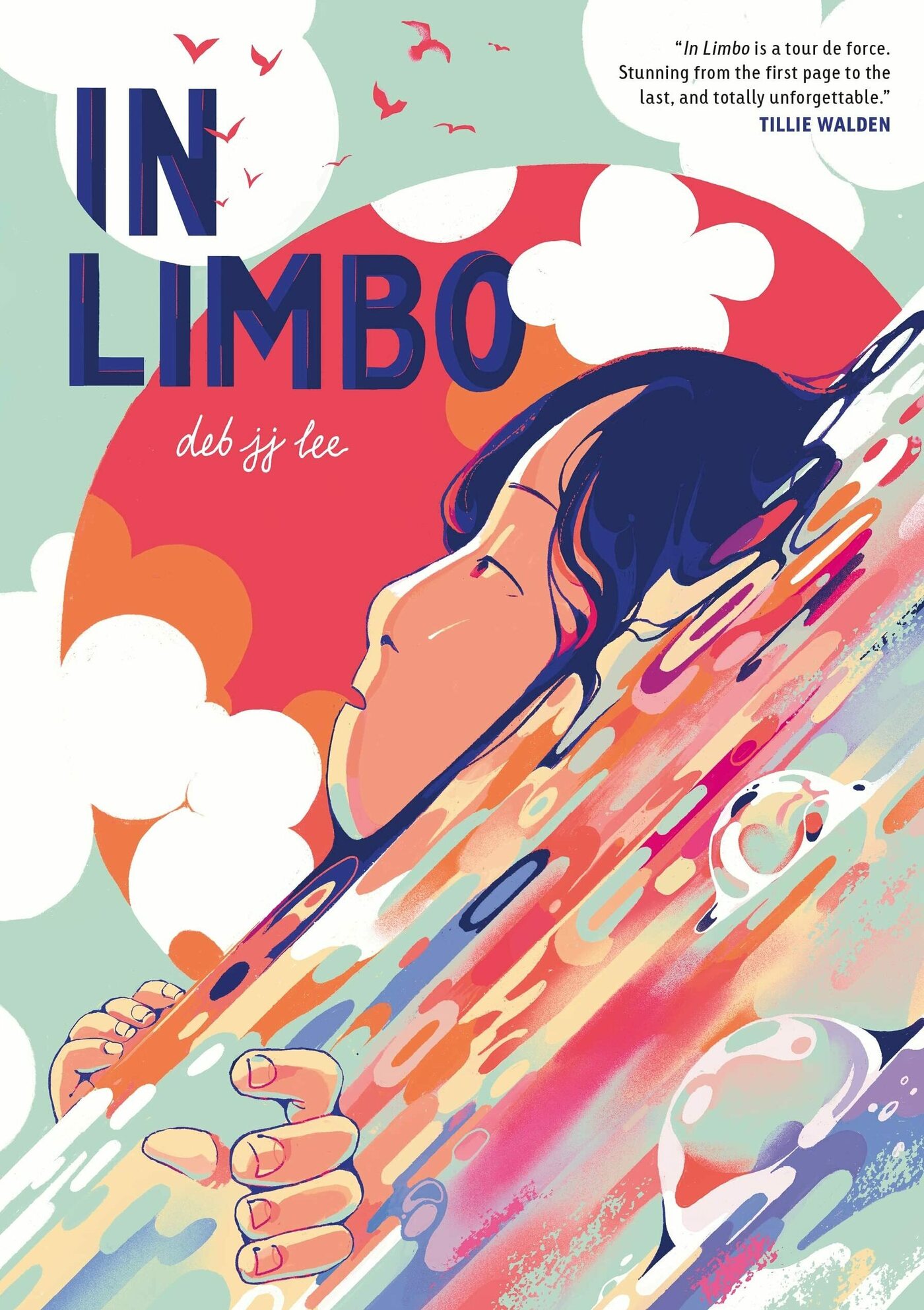

In graphic memoir ‘In Limbo,’ a Korean American finds healing and humanity

Deb JJ Lee/First Second Books

Editor’s Note: This interview contains a discussion of self-harm. If you or someone you know may be considering suicide or is in crisis, call or text 988 to reach the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

In Limbo is not your typical graphic novel by a first-generation American.

Instead of focusing on race and identity like many books by authors of this genre, relationships and mental health take center stage in Deb J.J. Lee’s debut young adult memoir, published last month by First Second Books.

Featuring moody, nearly photographic illustrations in hues of blue-gray, the book chronicles the intense pressures that Lee — a Korean American born in Seoul — faced growing up in Summit, N.J. Although their mother, a Korean immigrant, was supportive of Lee’s passion for art, she had a mercurial temperament and was physically abusive. Lee was also chronically insecure about their social standing at school. When Quinn, one of Lee’s few friends, started hanging out with other people, Lee was devastated. Throughout their childhood, Lee struggled with anxiety and depression. By the time they graduated high school, they had attempted suicide twice.

For many years, Lee blamed their tumultuous relationships for their mental health issues. But through self care and therapy, Lee was able to rebuild their life. Retelling their story helped too. Through the writing and drawing process, Lee says they “learned that everyone is a three-dimensional, flawed human being” — including themself.

Lee, 27, a freelance illustrator who has been commissioned by Google, Lego and the band Japanese Breakfast, is based in Brooklyn, N.Y. In 2018, they worked at NPR as an illustration intern. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Although your Korean American heritage takes a backseat in this book, race still plays a role. You grew up in Summit, a predominantly white town, but every Saturday, you went to Korean school in Tenafly, N.J., which has a large population of Korean immigrants. There, you say, you felt like an outsider. Why was that?

Because I was from Summit, people would say, “Yo, you’re so white — what’s wrong with you?” All those kids were good at speaking Korean because all their friends were Korean — they had a reason to speak Korean. I didn’t have that. I’d have to go back to Summit where I would just be “white” again and speak English all the time. I wanted to fit in so bad [in Summit] that I tried to force myself to forget the Korean part of myself. It was a survival mechanism.

Deb JJ Lee/First Second Books

What was high school like for you in Summit? In your book, you share how you were often confused for another Asian kid and that you were frustrated by your Asian features.

I was an outcast. I wasn’t invited to parties. People forgot I existed. People didn’t interact with me. I always thought: They don’t like me. They hate me.

And that contributed to some of the issues you wanted to confront in your book.

There was a lot of baggage that I hadn’t been able to sift through from high school, middle school or elementary school that I needed to process. In order to do that, I needed to publicly talk about it and archive everything I went through.

You endured physical abuse from your mother, who at one point, hit you for talking back. And you open up about two suicide attempts, one in elementary school and another in high school. What was it like having to recount these difficult memories?

The experience of writing it down wasn’t as harrowing as it could have been. I had to repeat the story multiple times to different therapists [throughout my life]. Writing it was like, yeah, this happened. And now that it’s out in the world, it’s like, c’est la vie.

A lot of your book focuses on your friendship with Quinn, who you met in sophomore year. By senior year, they were hanging out with different people. And you had a tough time dealing with that. When they found out you tried to commit suicide, they distanced themself from you. Have you heard from them at all since the book came out?

When I told them about it [in 2018], they seemed reluctant while staying quasi-happy about the news [that I was writing a book that included them in it]. But I don’t think we’ve seen each other face to face since 2017. I also have some reason to believe they don’t want to read the book.

Deb JJ Lee/First Second Books

But you say you have heard from Quinn’s friend group.

Since the book came out, I’ve gotten more closure. They told me they had no idea what was going on. They only know what they heard from Quinn. They thought that we didn’t talk to each other anymore because I tried to unalive myself because I was jealous.

They didn’t know you were dealing with other issues at home and with your mental health. Did that feedback help you realize anything about yourself in high school?

People did not hate me as much as I thought they did. Everyone is so wrapped up in their own world, what’s going on in their lives, their dating drama. The reason I wasn’t invited to parties and things was probably because I didn’t seem like I wanted to be invited. I was just a regular person.

You show great empathy for the people in your life, including your mother who, despite her flaws, was supportive of your journey as an artist — and also yourself. How were you able to get to that point?

It’s more acceptance than empathy. For my mom, I still don’t understand when she chooses to lean one side and then swing to the other, but part of healing from trauma is accepting the circumstances. For her to support my journey as an artist is a bigger deal than I thought. I thank my lucky stars that she provided what she could.

As for myself, it took a lot of improvement of my self esteem while writing and editing the book. I’m secure enough to show everyone my flaws and let them be. I give most of the credit to my friends, who are constantly reassuring me of my worth.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.