Hunt returns to ‘fiscal orthodoxy’ in face of grim public finances

Rarely has a chancellor been confronted with a horrible set of draft economic forecasts by the UK fiscal watchdog like those presented to Jeremy Hunt over the past few weeks.

But unlike his predecessor Kwasi Kwarteng, Hunt was willing to accept dire predictions for the economy and public finances put forward by the Office for Budget Responsibility, and take firm action in response.

He used his Autumn Statement to announce a £55bn a year fiscal consolidation involving sweeping public spending cuts and tax rises.

“With just under half of the £55bn consolidation coming from tax, and just over half from spending, this is a balanced plan for stability,” Hunt told the House of Commons.

He issued a rebuke to Kwarteng and his “mini” Budget that unleashed turmoil on financial markets by containing £45bn of unfunded tax cuts and failing to feature a set of OBR forecasts.

“Unfunded tax cuts are as risky as unfunded spending, which is why we reversed the planned measures quickly,” said Hunt.

Kallum Pickering, economist at Berenberg Bank, said the Autumn Statement marked “the return of fiscal orthodoxy”.

The big underlying problem for Hunt was the OBR had not just forecast the UK economy was already in recession, but that the five year outlook was also much weaker.

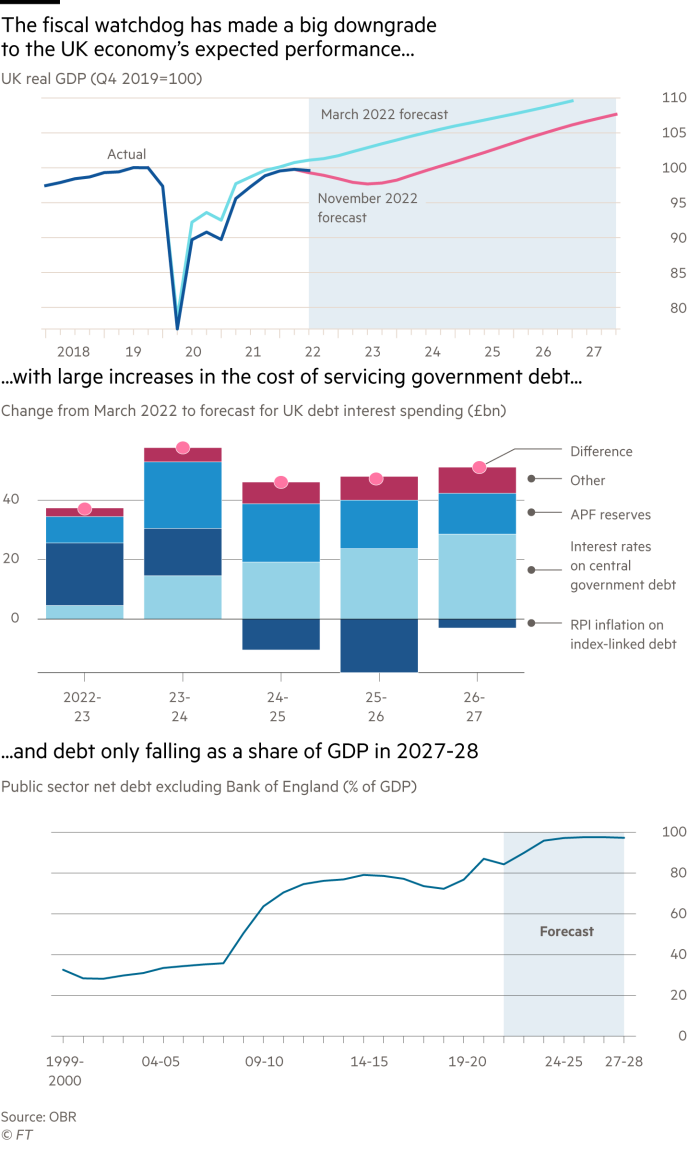

It forecast no economic growth at all for the whole of this parliament, between late 2019 and late 2024. Cumulative growth between 2019 and 2027 was 3.4 percentage points lower than the OBR forecast in March.

The weaker outlook reflected downward revisions to past data that mostly reflected worse performance during the Covid pandemic, a view by the OBR that the economy is currently overheating, and a downgrade in its assessment of the potential for future growth.

This in turn made the medium term outlook for the public finances appear exceptionally weak.

With interest rates expected to remain elevated for a long period, the OBR substantially increased its forecast for the cost of servicing government debt. This added £52bn to public borrowing next year, equivalent to about 2 per cent of national income, and increased the budget deficit by £46.6bn in 2026-27.

Meanwhile, the uprating of state pensions and welfare benefits in line with high inflation has the effect of raising the expected cost of such support because the bill would be permanently more expensive for the government.

Putting these effects together, Hunt was presented with public finance predictions by the OBR over the past few weeks that showed the underlying level of government borrowing ballooning to £106.4bn in 2026-27. In its March forecasts alongside the Spring Statement, the OBR had calculated a deficit of just £31.6bn in that year.

Martin Beck, economic adviser to the EY Item Club, a forecasting house, said “the OBR’s “poor prognosis for the economy’s prospects” left the public finance forecasts “fac[ing] challenges accordingly, with substantial upward revisions to public borrowing over . . . five years”.

With such a large downgrade to the underlying public finances, the OBR told Hunt before the Autumn Statement that he was not remotely on track to meet any of the government’s existing fiscal rules. The main rule had been that debt as a share of gross domestic product should be falling by the third year of the OBR forecast.

Hunt’s reaction was to draw up new fiscal rules, including that debt should be declining as a proportion of gross domestic product by the fifth year of the OBR forecast.

Paul Dales, economist at Capital Economics, said Hunt had “relaxed” the rules, making them easier to hit.

But changing the rules did not allow Hunt to show they were passed without large spending cuts and tax increases. If the chancellor had done nothing, the OBR calculated the government’s debt would still have been rising as a share of GDP in 2027-28, the fifth and final year of the fiscal watchdog’s forecast.

Some economists wanted Hunt to loosen the fiscal rules further, rather than squeezing spending and raising taxes.

Hailey Low, economist at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, a think-tank, said the “mini” Budget debacle “left the chancellor rushing to unleash a fiscal contraction to fulfil arbitrary fiscal targets amid the headwinds the economy is facing”.

Hunt disagreed. He bit the bullet and sought to fill the gaping hole in the public finances by introducing £55bn of spending cuts and tax rises. There are notably cuts to day-to-day spending on public services and capital investment.

But the overall budgetary tightening is less severe than it might have been because Hunt’s measures offset net tax cuts and spending increases from several government statements and emergency interventions since the March Spring Statement.

The timing of Hunt’s measures vary markedly. Spending cuts, which rise to £30bn a year, are delayed until the recession is forecast to be over. For the next year, the government is poised to support the economy with its cap on household energy bills and some extra funding for schools and hospitals.

Tax rises are coming earlier, however, with £7bn of revenue raising measures taking effect in April, and then increasing steadily to raise £25bn a year by 2027-28.

Even as Hunt announced the largest budgetary squeeze since 2010, the OBR said he had not been as prudent as former chancellors in building resilience into the public finances.

In the end, after the £55bn of spending cuts and tax rises, the fiscal watchdog judged Hunt was likely to meet his new budgetary rules with only roughly £10bn of fiscal headroom to spare.

“This chancellor has left himself comparatively little headroom against his proposed new fiscal targets relative to previous chancellors,” said the OBR.

It was enough, however, to demonstrate that economic orthodoxy had returned to 11 Downing Street after Liz Truss’s ill fated premiership, and the market reaction to the Autumn Statement was muted.

The government is using fiscal policy to support the economy through a recession and then consolidating the public finances thereafter. And it is imposing just enough difficult fiscal measures up front to demonstrate it is serious to the markets about spending cuts and tax increases.

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.