How much storage you should leave unused on a Mac’s SSD?

If you’ve looked into how much storage space to keep unused on an SSD, you likely came across recommendations ranging from 0 to 50 percent and may be frustrated about how to sort out the right number. When you have a 1TB or 2TB drive, keeping even 20 percent (200GB or 400GB) unused might seem wasteful and costly.

For most consumer uses and even many professional ones, you can err on the low side of empty storage, down to even filling a drive up to what you might have thought was 100 percent full, depending on how you use the SSD now and plan to in the future. You may decide after reading this column not to worry about free space at all or opt to keep empty up nearly 30 percent of your SSD.

Let’s start with the gory details. (If you want to avoid those, and skip to advise, go to the section after the one below.)

Why an SSD needs empty space

SSDs are quiet, low-power, long-lasting, and resilient, but they will eventually fail, just like a hard disk drive (HDD), although in a very different fashion. This analysis from storage and backup firm Backblaze from 2019 remains a thorough, not-too-technical read about the differences between the two kinds of storage.

An HDD has lots of internal moving and spinning parts while an SSD is “solid state” and everything occurs as the result of an electrical operation within the drive’s chips. More specifically, reading data from an SSD memory cell uses very low voltage and incurs no real wear; writing data requires higher voltages that eventually wear out the storage bits.

SSDs have an estimated finite number of times each cell can be written along with an overall anticipated total writes to the drive over its lifetime. On an HDD, because data writes involve magnetic changes, the same level of wear doesn’t occur for updating files at an identical location on a disk. (You can use a utility like DriveDx to provide an ongoing estimate of the remaining lifetime on an SSD or HDD. It has some Apple-related limitations on monitoring external drives.)

SSD firmware works to rotate through memory cells, units that store 1 to 4 bits each, and level the wear across the entire drive. Otherwise, a frequently used cell would burn out far in advance of other cells. Every time you save a document, copy files, or otherwise cause data to be written to an SSD, or whenever the operating system takes an automated action of the same sort, the cells that the SSD writes to are entirely different than where the previous data was stored. The SSD firmware tracks all this—it’s seamless to the operating system and you.

Complicating this is that SSDs group memory cells into larger units known as pages, and pages are grouped into blocks. Depending on the SSD’s chips’ design, a page might hold 2K to 16K and a block may be between 256K and 4MB. Because of how free storage is distributed, whenever an SSD writes data, it may be able to write just a page’s worth, or it might be required to write an entire block—so a single bit of data changed could mean writing as much as 4MB.

Overprovision: Space to extend an SSD’s life

That overhead coupled with some cells failing early led manufacturers to overprovision the storage by building in extra capacity you (and the operating system) never see. This invisible portion allows an SSD to write smaller pages more frequently than bigger blocks, preserving its overall lifespan. An article at drive maker Seagate likens it to the 15-square game.

This overprovisioned storage is hidden in drive marketing by exploiting the difference between powers of two and powers of 10. A “500GB” drive offers 500 billion bytes of storage. However, memory chips are denominated in powers of 2. The closest value to a billion is a “gibibyte” or GiB, based on units of 1024 (2^10): 1 GiB is 1,073,741,824 bytes. A 500GiB drive holds 537GB of storage, but you only see 500GB—that extra 37GB is the inherent overprovisioned amount for the drive.

For most consumer purposes, even when an SSD is your startup volume, you could hit 100 percent usage of an SSD’s storage as shown available in the Finder and still experience a long and happy life from your drive.

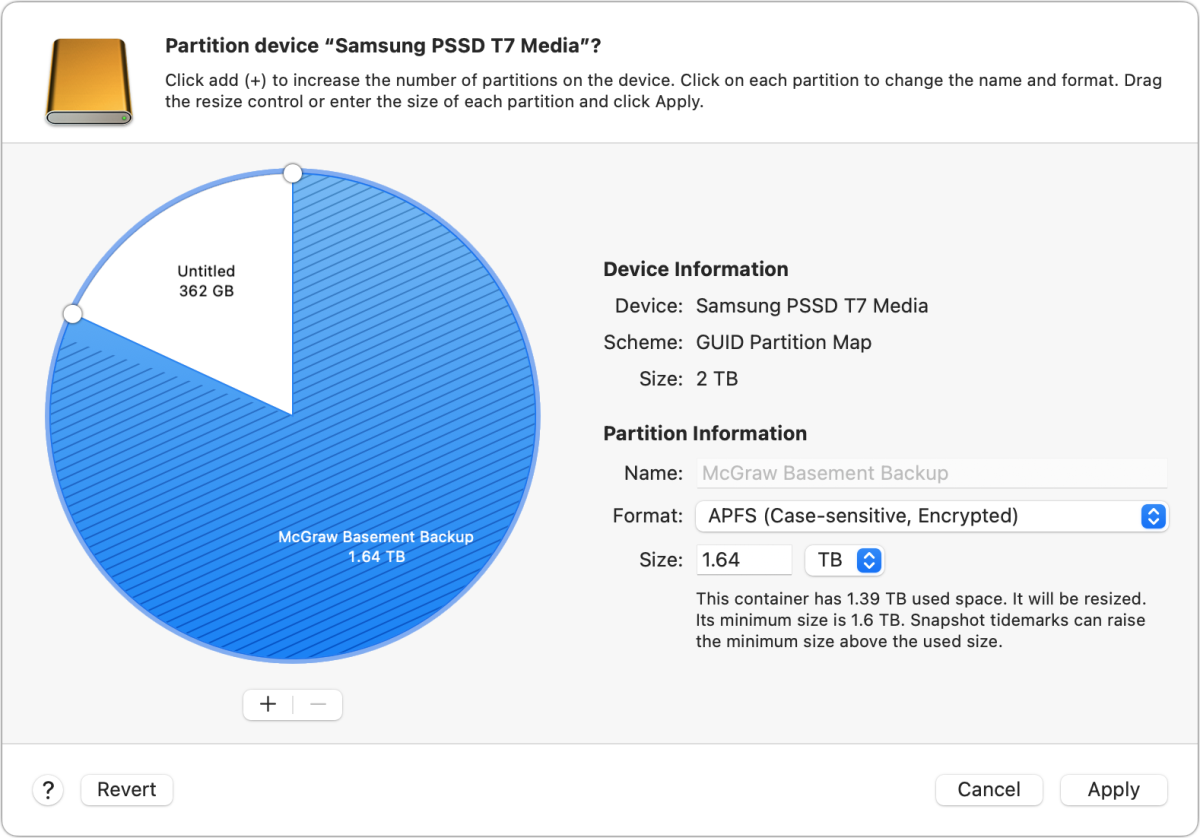

SSDs have an estimated lifespan in typical use of about 5 to 10 years based on a number called terabytes written (TBW), reflecting how a drive should function with well-distributed write operations through a certain amount of data. With Samsung’s affordable T7 external drive series, the 1TB model has a 360TBW value, equal to an average of 200GB of data written every day across 5 years. Higher capacities have higher TBW numbers as they’re expected to experience more writes relative to their size.

Samsung also offers a brief and understandable white paper on overprovisioning aimed at data-center users, but which has an incredibly useful three-line chart that lets you decode the utility of having more unused storage on a drive. These factors are critical in data centers where SSDs experience far heavier quantities of writes than on a personal computer.

- With no overprovisioning, something only available in data-center-oriented drives, with no secret SSD stash, the lifetime factor is shown as 1.

- Shift up to 6.7 percent, the amount that Samsung and other SSD makers bake into their consumer drives, and the lifetime factor more than doubles to 2.09. That’s the baseline used for Samsung’s TBW figures for its consumer-level SSDs.

- Preserve a total of 28 percent, and the factor jumps to 5.22. That could take a drive that might last 5 years and extend it to about 12 years. But it’s more likely you’d want that overhead on an SSD you use far more intensively for file writing than an average user, such as one used with daily live recording or audio and video editing.

How much storage should you set aside as empty? Let’s look at that.

How much to overprovision

Here’s a quick rundown of recommendations for overprovisioning, excluding the 7 percent or so built into Apple, Samsung, and other consumer SSDs:

- 5 to 20 percent for a Mac startup volume or external drive, depending on intensity of usage

- A higher percentage could be warranted for M1-series Macs

- Close to 0 percent for external drives used mostly for offloading data that’s then read later but rarely rewritten

A startup volume on a Mac will experience many more write operations than most external drives. You might opt to always keep a significant fraction of your startup volume empty, from 5 to 20 percent on top of the inherent amount built into the drive. I’d settle for the lower range for typical use and the higher end if you use software that’s constantly writing and moving files to the drive.

It’s always a good idea to keep at some storage free for a macOS startup volume, anyway. Apple will fill up empty space on the main volume partition as necessary for temporary files, “swap” files (used when memory is under pressure to write data to the drive), and Time Machine snapshots before they are transferred to a Time Machine volume.

Unused storage on an SSD is treated as free space: for the purpose of writing data, storage that the operating system hasn’t allocated counts towards overprovisioning.

There’s an extra bit of worry in keeping the built-in SSD on M1-series Mac happy for as long as possible. Apple engineered the M1-series chips so that a Mac cannot boot if its internal SSD has failed, as it stores the provisioning information required to authorize starting up from an external drive. If your internal SSD fails prematurely, you can’t simply switch to an external SSD as you could with an Intel Mac. Factor that into your usage.

On an external SSD not used to start up your Mac, you should make your decision also based on its intensity of use. If you’re offloading data to an SSD or using it as a Time Machine volume, which adds data incrementally and overwrites only as necessary, you can push close to full utilization without worrying about reducing lifespan. With a drive used mostly for reading data, it will experience very little wear.

However, if your external drive is thrashed with reads and writes all the time—particularly for large files that are erased, modified, or moved—preserve a margin, even a significant one, unless you’d rather use all its space and budget for a faster replacement cycle.

This Mac 911 article is in response to a question submitted by Macworld reader Donald.

Ask Mac 911

We’ve compiled a list of the questions we get asked most frequently, along with answers and links to columns: read our super FAQ to see if your question is covered. If not, we’re always looking for new problems to solve! Email yours to [email protected], including screen captures as appropriate and whether you want your full name used. Not every question will be answered, we don’t reply to email, and we cannot provide direct troubleshooting advice.

For all the latest Technology News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.