Appreciation: Why New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl was the last of a breed

Peter Schjeldahl, the eminent and widely read New York art critic, died Friday at his country home in the tiny upstate town of Bovina, near the Catskills, where he and his wife, former actor Brooke Alderson, lived. He was 80.

In the mid-1960s, Schjeldahl (pronounced SHELL-doll) began to contribute gallery reviews to the Village Voice, where he would join the staff full time in the following decade. Since then, there was barely a moment when his eloquent, lapidary observations on art old and new could not be read — in addition to the Voice, in the New York Times, ArtNews, Art in America, 7 Days and other magazines, plus assorted gallery catalogs. In 1998 he began a nearly 24-year stint on the art critic’s perch at the New Yorker where, following the New York School’s 1950s heyday, Harold Rosenberg had held forth. Like Rosenberg, the great champion of Willem de Kooning’s paintings, Schjeldahl was similarly enthralled with the Dutch immigrant, treasuring a simple abstraction the artist brushed on newsprint. It held pride of place in the writer’s apartment in Manhattan’s East Village.

I met Schjeldahl early in 1982. He had sent me a fan letter (remember mail?) at the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, where I worked, after I defended a controversial June cover piece he wrote for the Village Voice. Its subject was the newly reviving Los Angeles art scene, which had risen like a rocket in the ‘60s, stumbled in the ‘70s, and was experiencing a veritable boom. His article, a decidedly mixed review of the goings-on, burst the local bubble of excitement.

The howls from L.A. about faults in the home team emanating from the Other Coast were surely audible on the moon.

I was a fledgling art critic, and his column had indeed trafficked in a number of groaning clichés — several still operative in other writers’ work — about an unhurried, horizontal place that couldn’t be more different from his stressed-out, vertical and beloved New York City. (When he was hired as the New Yorker’s art critic, few were surprised since the magazine’s name also perfectly described him.) But so what if he got some stuff wrong?

Duly noting several triggering chestnuts, I also wrote how being angrily dismissive of anything less than solid praise for an art scene newly on the upswing — and drowning in vacuous self-promotion — manifested a lingering streak of provincial diffidence. Several of his critical insights were quite acute. And unlike the civic public relations torrent gushing around the new institutional promise of the Getty, Museum of Contemporary Art, an expanding Los Angeles County Museum of Art and a downtown gallery scene, the stylish writing was literate, funny, opinionated and biased — just what one wants from a critic.

Schjeldahl had done Los Angeles a favor. He helped us see ourselves, sharpening our own take on local pros and cons — if we were willing. Rather than yelp, I suggested it would be best to beat him at his own game.

I followed up on his accompanying dinner invitation the next time I was in New York. I was nervous about meeting Peter and Brooke. Their daughter Ada Calhoun, then 6 (now a successful writer), was also there. By dessert I had decided that if anyone could be raising such a cool kid, they must be OK.

A born-and-bred Upper Midwesterner, Schjeldahl was a belletrist as a writer — a once fashionable, now vaguely disreputable genre of fiction, poetry and essay writing with an acute concern for “fine language,” which he, virtually alone, managed to make worthwhile for art criticism during a dense era of academically minded theory. (His loosely libertarian politics sometimes made me wince.) In the cramped home office at the back of the family’s fifth-floor walk-up on St. Mark’s Place, there was a desk, a cluttered table, some file cabinets, a few wilting spider plants and his most treasured single object — a large open dictionary, worn and many inches thick. When Peter, a lapsed poet, plucked the right if elusive word from his head as he wrote, he’d turn to the book for further insight and etymology, sometimes being led elsewhere to something even better.

Words mattered to him. Sometimes the resulting text became overly precious. Mostly, though, it radiated his unwavering belief — one I happen to share — that pleasure is the driving impulse behind the best art, even when its subject matter might be grim, as well as a key to any critical response to it. He owed the reader of his prose as much.

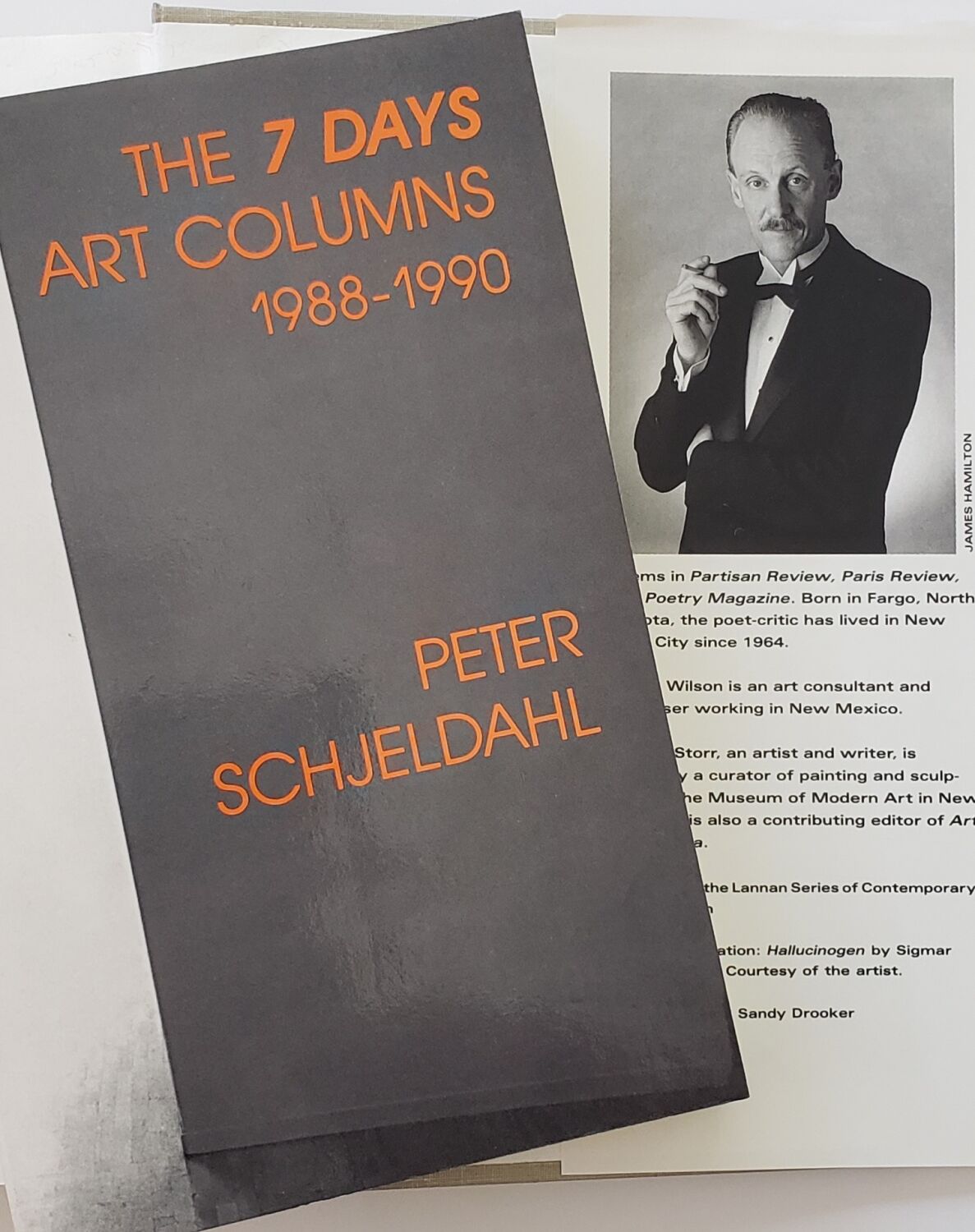

A short-form essayist — Schjeldahl never wrote a book, despite more than one failed attempt — he published several collections of his writing. The two best are “The 7 Days Art Columns, 1988-1990” (1990) and “The Hydrogen Jukebox” (1991). The former was lightly edited by the writer, the latter deftly assembled to cover a dozen earlier years by editor MaLin Wilson-Powell, whom Schjeldahl generously credits in the preface with having “invented” the project. (Disclosure: Wilson-Powell edited my own 1995 collection, “Last Chance for Eden.”) The title essay of “Jukebox” is from 1978, subtitled “Terror, Narcissism, and Art,” and it charts a gnawing sense of cultural confusion and social malaise that, unbeknownst then, would soon be engulfed by the manifold corruptions of the Age of Reagan.

Both collections were published in its aftermath, once the New York art world had been irreversibly transformed into a massive, expanding, international marketplace, with unimaginable amounts of money sloshing about. The “Jukebox” jacket flap features a photograph of Schjeldahl shot by his friend, James Hamilton, in which the author, never a sartorial star, is dressed in a black tuxedo and crisp white shirt, arms protectively crossed, cigarette in raised hand, hair slicked back, and eyebrows arched, like something from Weimar Germany by Max Beckmann (one of his favorite painters). Half hilarious, half chilling, it’s portrait photography as art criticism: Things will not end well, one thinks, and soon after the roof did indeed fall in. The roaring market collapsed.

“7 Days” is a whiz-bang record of the essential if short-lived magazine of that name, where Schjeldahl wrote a rip-roaring weekly column that for me represents the peak of his life as a working critic. Miss an installment, and you were hopelessly out of touch with the roller-coaster New York art scene at the 1980s’ end. He describes events like a sportswriter (a baseball fanatic, two of his idols were master wordsmiths Red Smith and Roger Angell), taking readers directly to the scene of the art.

“Like a pilot taking an aerial photo prior to crash-landing,” his inaugural piece, wittily titled “Hello,” began, “I’ll use this, my first column, for a quick overview of terrain I’m about to be part of: the situation of art in New York, where almost everything appears to be going wrong and there are inklings of a new, probably glorious era.”

What I gleaned from it was confirmation of an inchoate need to be intensely local in writing art criticism, which is about the deeply lived experience of art at hand. (Today, the internet has undercut all that.) “Now, go look at some art” his first column instructed readers in closing, “and meet me back here next week.” I did, even though I was 3,000 miles away. While first-person was then frowned upon in journalism, a sense of it had to be conveyed.

Our friendship lasted about 25 years. There were regular bicoastal visits and a couple jaunts to Mexico City and Oaxaca, Mexico, favorite places, including one to the latter during which the long-teetering Herald Examiner happened finally to go under — on Day of the Dead — and The Times tracked me down with a job offer. The friendship didn’t so much end as simply wither.

A recovering alcoholic without an extensive repertoire of personal skills, Peter could certainly be indiscreet. I once shared some confidential information with him since I desired his specific feedback on the subject, but I stressed that it had to remain private. A few months later, a mutual friend mentioned said information to me, and nonplussed, I asked how she knew. “Peter told me,” my friend replied. He was suitably apologetic when I yelled through the phone.

I’m not certain why, but one day in the mid-aughts it occurred to me that the only times I ever spoke with Peter were when I telephoned him, or when I was in New York, or on the rare occasion he was coming to L.A. and needed a dinner companion. To test the hunch, I decided to stop initiating contact. Two years of silence later, I concluded that was that.

And it was. There was no rancor. We both already knew too many people to notice one had gone missing. Writing is a solitary profession, and Peter was simply wired to thrive inside his cocoon.

The silence also had a minor back story. In the spring of 1986, I made a pact with Peter. The idea was his. On a considered impulse I had quit cigarettes, a relinquished addiction that was causing serious pain, so I called the only other chain smoker I knew well to commiserate about the tormenting difficulty.

“Let’s do it together,” Peter said. “I’ll quit too. If you’re feeling an unquenchable urge, call me immediately and I’ll talk you down. I’ll do the same with you.” For me, thus began an excruciating but ultimately successful several months of breaking the deadly habit, just knowing a lifeline was available.

Several weeks in, anxious and feeling like I was about to fold and track down some luscious nicotine at the closest 7-Eleven, I dialed up Peter in New York. As we chatted about my wavering resolve, I heard a familiar sucking sound on the other end of the line.

“Are you smoking?” I asked.

“Yes,” came the dispassionate reply.

“I thought you were supposed to call,” I said, slightly exasperated. “When did that happen?”

“I don’t know,” Peter said. “I think the next day. Or maybe that afternoon.”

I haven’t had a cigarette since. Peter died of lung cancer, which was no surprise to either one of us — or to anyone else who read “The Art of Dying,” his wrenching December 2019 essay in the New Yorker printed under the headline “77 Sunset Me.” The essay detailed his roiling response to a late summer diagnosis of advanced disease that gave him six months to live.

I don’t recall the magazine publishing a subsequent amplification for shocked readers, but word eventually got around that a new cancer treatment was bringing unexpected results, and his byline began to appear again. Six months became 12, then 24. His final piece, an ode to the great Dutch Modernist Piet Mondrian, ran in the Oct. 3 issue, 2½ years on.

I could — and did — still read him, although in the last many years with less enthusiastic interest. In a dizzyingly globalized art scene, New York could no longer be what it had been, and Schjeldahl’s fading passion for a dissipating, city-centered new-and-now couldn’t help but come through. Unlike 7 Days, getting behind on the New Yorker didn’t much matter. Now his best writing was historical, like that sparkling final essay on the radicalism of Piet Mondrian, dead now 78 years — almost as long as Peter was alive.

That he wrote it through what must have been an unimaginably painful time is a testament to what great art and powerful writing meant to him. And hopefully to us.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.