‘Always Running’ is more than cholo lit — it’s a manual for L.A.’s salvation

For most of my life, I didn’t think “Always Running” was meant for someone like me.

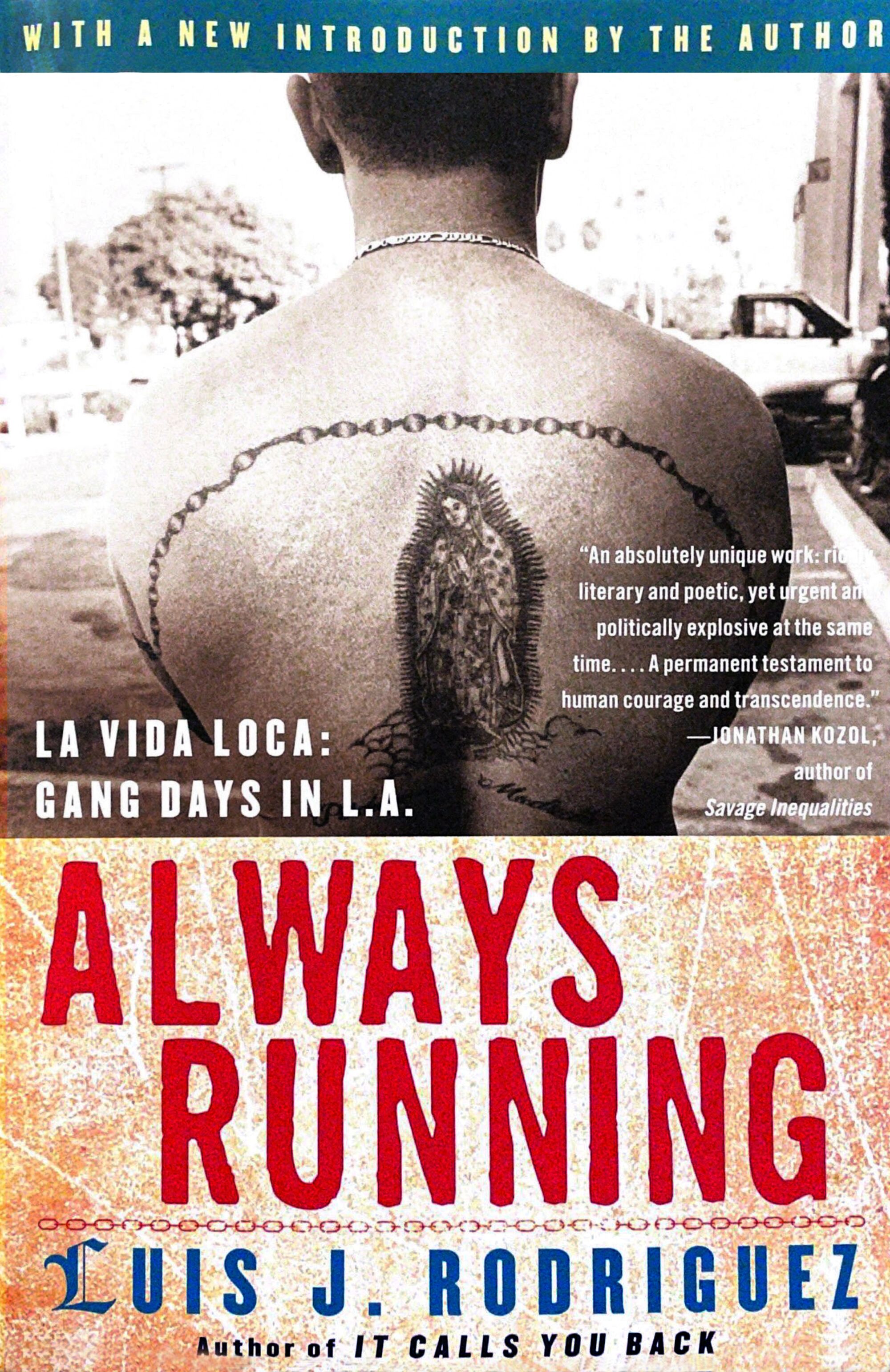

Luis J. Rodriguez’s account of his first 18 years — from El Paso to Watts, Reseda to the Lomas barrio in South San Gabriel — has long drawn praise and criticism for its unflinching look at Chicano gang culture during the 1960s and ’70s. Its descriptions of sex, violence and drug use continue to titillate teenage readers and draw bans from schools and libraries across the United States.

When I finally paged through a copy some time after high school, I did it mostly to see if it was as “real” as friends made it out to be. It was. I never lived la vida loca, but Rodriguez’s taut, melancholy sentences felt like the exploits of my cousins in East Los Angeles or the San Fernando Valley whenever one of them had rolled with the wrong crew yet again.

Still, “Always Running” didn’t hit me on a personal level. I was a nerd, after all, from a blue-collar Latino neighborhood of single-family homes bordering the territory of one of Anaheim’s biggest and oldest gangs. I felt only the “bad” kids — the ones in danger of dropping out of high school, the homies cycling through the carceral system — needed to read about Rodriguez’s redemption. There was little of value for a “good” kid like me, or any adult.

I rarely thought of Rodriguez’s memoir in the decades that followed, even as I enjoyed his subsequent essays, poems, novels and speeches. I also found it impressive that a bestselling author like him did so much besides just write.

He and his wife, Trini, opened Tia Chucha’s Centro Cultural in Sylmar in 2001. His many appearances, from universities to bookstores, public schools to prisons, made him my type of public intellectual. Even Rodriguez’s quixotic forays into politics, twice running for California governor on the Green Party ticket, drew my respect — if Norman Mailer and Upton Sinclair did it, why not a Chicano?

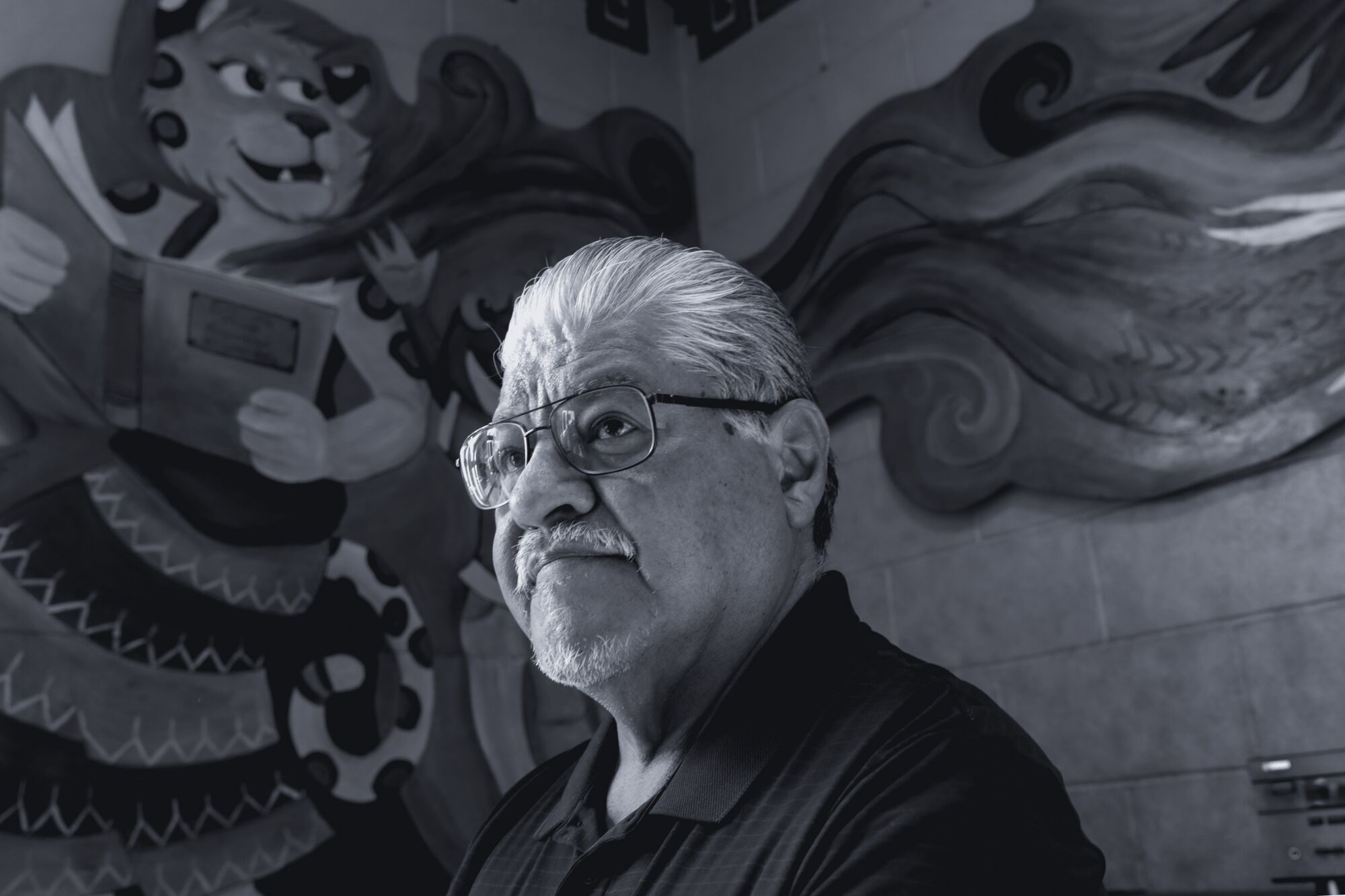

Luis J. Rodriguez

(Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times)

Yet the public always returns to “Always Running,” for better or worse. And it shows up perennially on best-of lists about L.A. and Latino literature. When it popped up on The Times’ “Ultimate L.A. Bookshelf” — a popular favorite among survey writers — I agreed to write an essay and decided to reread it.

I expected to find a better-than-average young adult novel, and carved out a couple of days to finish it.

I was done within half a day.

As a memoir of Los Angeles, it’s a fascinating slice of regional history. The southeast L.A. of Rodriguez’s time is a working-class white enclave. The San Gabriel Valley is still rural, and residents are mostly Chicano and white. You see in real time the rise of gangs, at first mostly a collection of neighborhood toughs instead of vassals of the Mexican Mafia.

Rodriguez wasn’t going for an anthropological tract, though. He wrote an indictment, not a confessional — and his target was one of L.A.’s main civic religions: violence.

A young Rodriguez learned early on that whoever weathered it best and dished it back even worse were the victors. After a new gang began to terrorize his junior high, he wrote, “All my school life until then had been poised against me: telling me what to be, what to say, how to say it … I wanted the power to hurt someone.”

It’s a mantra that could’ve been uttered by Harrison Gray Otis, Sammy Glick, Eazy-E or any other L.A. striver, real or fictional.

Violence studs each page, but the gang fights, stabbings, rapes and shootings Rodriguez lists with escalating numbness aren’t even the worst of it, nor the individuals who commit them. All interpersonal and individual violence, Rodriguez argues, derives from systemic violence that serves as the baptismal font for Los Angeles. It’s the everyday racism Rodriguez endured from teachers and classmates alike. The marginalizing of working-class neighborhoods. The fact that his dad — a former principal in Mexico — can be no more than a janitor in the Valley in the United States. Redlining, discrimination, policing and pollution.

And among the most ruthless actions is disinvestment. When there are no jobs or no education, communities and individuals enter cycles of violence from which few emerge. There’s a brief description of the 1970 Chicano Moratorium, the East L.A. march against the Vietnam War that ended in violence, Rodriguez’s arrest, and the death of three individuals, including pioneering Times columnist Ruben Salazar. But what hit harder in Rodriguez’s memoir was when the youth community centers opened with grants during the Johnson administration turned into drug dens once the money dried up.

“Always Running” is the literary companion to Mike Davis’ “City of Quartz,” published three years earlier. But while we all rightfully hail Davis as a prophet, we usually sequester Rodriguez’s insights to the genre of cholo lit.

To paraphrase Sinclair’s bitter riposte about the success of his 1906 exposé of Chicago’s slaughterhouses, “The Jungle,” Rodriguez aimed for L.A.’s brain, and by accident he hit it in the heart.

Even well-meaning fans do this. They’ll cite Rodriguez’s admission that he wrote “Always Running” as a warning to his son as proof that its intended audience was exclusively young men. But “Always Running” is hardly nihilistic or dour. While the gang violence in the book gets most of the attention, we need to finally listen to the salvation he offered to us all.

The most inspiring passages to my adult eyes are when mentors channel Rodriguez’s teenage rage into community action — walkouts, youth sports, protests, organizing. The story reaches a climax during a tense student assembly at Mark Keppel High in Alhambra, Rodriguez’s alma mater. By then, he was trying to work within the system, on his own terms, which also meant trying to reach out to the white students who saw no reason to side with Chicanos for anything, let alone demands for ethnic studies and hiring of more Mexican American teachers.

“This is not against whites,” Luis said to his fellow students. “It’s against a system that keeps us all under its thumb. By screwing us, the school is screwing you.”

Rodriguez has preached this lesson to anyone who’ll listen ever since.

When I finished “Always Running,” I realized the memoir wasn’t finished; Rodriguez’s decades-long witness to the depths and heights of his life are its continuation. Authors tend to write memoirs to look back from the better place they now occupy. Rodriguez wrote it knowing he wasn’t there just yet. He speaks now knowing we’re not there just yet. But, like the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. telling a Memphis, Tenn., audience on the last night of his life that he wasn’t going to see the Promised Land, Rodriguez knows L.A. can get there, even if he doesn’t.

So the work continues. Will we finally join him?

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.