In mid-2019, staff at the biggest hospital in Milton Keynes were struggling to access patient records and process imaging and scans because the internet connection was so poor.

“Our digital infrastructure was grinding to a halt,” said Oliver Chandler, head of IT technical services at Milton Keynes University Hospital. Chandler’s team in the south-east England town contacted CityFibre, which had been laying full-fibre broadband lines in 275 areas across the UK, and within two weeks the hospital had a new network.

CityFibre is one of dozens of so-called alternative network providers — or “altnets” — that have taken advantage of the glacial pace at which BT, the one-time monopoly, was upgrading its network to rapidly dig up streets and lay fibre networks across the country.

It has now completed its rollout across its flagship area, Milton Keynes, with 90,000 homes and 90 per cent of the population able to access the network.

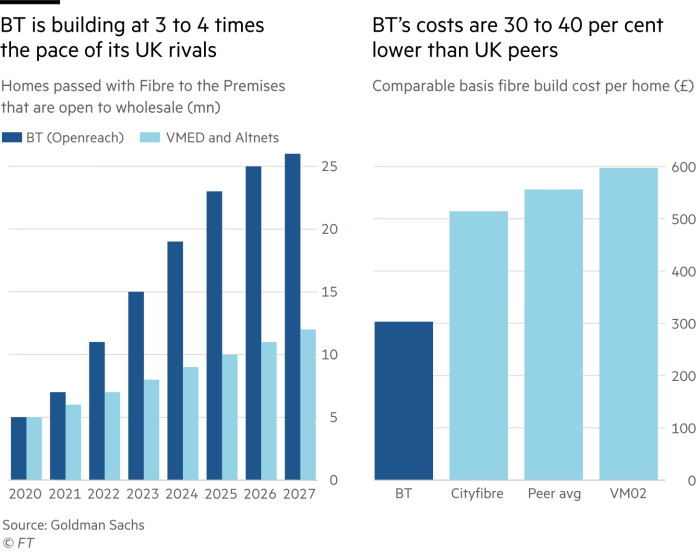

But over the past year, the battle between these challenger companies and the broadband incumbents has intensified as Openreach, BT’s networking division, and Virgin Media O2 have responded to the threat by accelerating their full-fibre rollout.

The question is whether the money will keep flowing from private equity funds and debt capital markets which have been the lifeblood of the sector, having pumped an estimated £15bn into a handful of the most promising companies.

This hinges on their assessment of whether BT can use its market dominance to build over networks being laid by newer entrants — including CityFibre, Hyperoptic, Gigaclear and Community Fibre — and convince existing wholesale customers like Sky and TalkTalk to stick with them.

Several smaller companies have already gone bust, with many more expected to follow. The vast majority of others are likely to be bought out by bigger players.

In 2018, as it became clear that the UK had fallen greatly behind almost every other developed nation in upgrading its network, the government started to encourage these alternative providers, hoping a more competitive landscape would disrupt the market and bring faster internet to underserved areas.

“The arrival of our networks forced the incumbents to invest,” said Greg Mesch, chief executive of CityFibre.

“If it wasn’t for us, we would still have copper and poor internet across the country,” he added, referring to the copper wire networks on which the vast majority of the UK’s broadband networks still run.

Fibre optic technology, by contrast, uses tiny threads of glass to carry modulated light along the same underground pathways, increasing the quantity of data that can be transported.

CityFibre, which is backed by £4bn from Goldman Sachs’ West Street Infrastructure Partners fund and Antin Infrastructure Partners among others, aims to offer its network to 8mn homes by 2025.

It is also bidding for contracts in the £1.5bn subsidies the government has put out to tender to lay full fibre in rural areas. If it wins these, it believes it could reach 2mn more homes in the same timeframe.

The success of each altnet depends on its ability to capture and retain about 30 per cent of customers in any region, industry insiders say.

In Milton Keynes, where BT has made limited progress in fibre rollout, CityFibre has managed to capture about 20 per cent of the market through wholesale deals with players such as Vodafone and TalkTalk; it hopes to reach between 60 and 70 per cent.

But BT has accelerated its fibre rollout elsewhere in the UK over the past two years, and committed to spend £15bn to reach 25mn homes by 2025. Virgin Media O2 is upgrading its network to reach about 15.5mn premises by the end of 2028, and is seeking investors for a new venture to build a separate fibre network that will connect 7mn homes.

“If you add up all of the fibre being built, we’re going to be able to service the country three times over,” said Dana Tobak, chief executive of Hyperoptic, an altnet that has laid fibre for 750,000 homes in some of the most densely populated cities in the UK and is backed by private equity group KKR.

“Some will fail and some will make it. No one expects in the long term for there to be more than three or four networks, so it then just becomes who [fails] and when,” she added.

Some companies’ fate will hinge on whether their backers’ wallets remain open. Upp, an altnet laying fibre across Norfolk and Lincolnshire, has received £1bn in financing from LetterOne, the investment group founded by Russian billionaire Mikhail Fridman, who recently stepped down after being hit by EU sanctions.

Openreach did not respond to requests for comment. Andrew Lee, head of telecoms research at Goldman, was bullish that Openreach can increase revenues and defend itself against challenger networks because it is pursuing the fastest fibre rollout of any company in Europe.

“The total addressable market in rolling out fibre has been reduced because of BT’s massive acceleration,” he said, adding that the incumbent’s existing customer relationships give it an advantage.

Altnets have already moved into most locations in the UK that have some commercial promise, although this has left glaring gaps that government subsidies have done little to remedy, such as Cambridgeshire and Dorset.

The House of Commons public accounts committee, which oversees government spending, recently said it was “not convinced that the [government] will deliver on time” on its latest goal of making gigabit broadband available to 85 per cent of the UK by 2025.

It called for “significantly increased investment” in rural and remote areas as “the commercial sector will unlikely be able to fill the gap”.

In the meantime, private investment and government subsidies remain available for altnets, but the pool of those able to forge ahead is shrinking.

“A few years ago, you could find anyone with a shovel and he or she would get funding,” said Olaf Swantee, a former EE chief executive who chairs Community Fibre, an altnet in London. “Today, there is a lot of money still available for those that have proven they can actually build and get customers.”

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.