Wind is blowing towards renewable energy in oil-rich Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico has for decades been a sea of hulking oil platforms. The Biden administration now wants to plant wind turbines there.

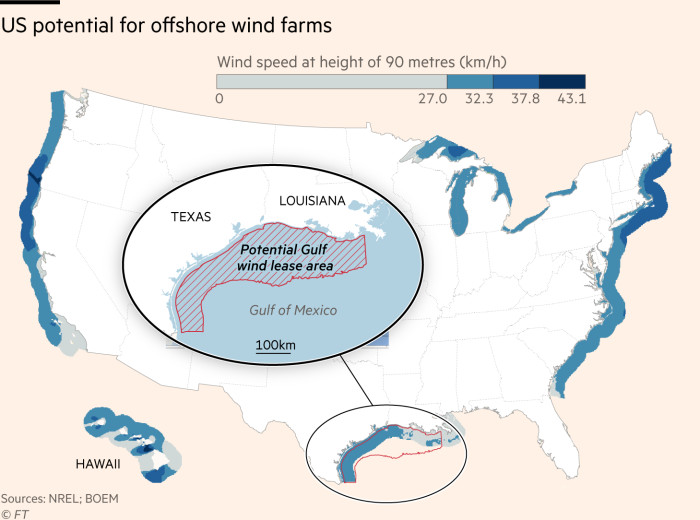

This week the US interior department called on companies to express interest in leasing in a 30m-acre area in waters off Louisiana and Texas, part of a push to build 30 gigawatts of carbon-free offshore wind power up and down the US coastline by 2030.

It would be a radically new look for the gulf, where offshore oil wells date to the 1930s and now account for 15 per cent of US oil production. As in the North Sea in Europe, new spending on wind could offset declining investment in oil megaprojects.

The federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management contends that the oil and gas industry “will most likely lead the way,” noting that some oil majors — all of them based in Europe — have set goals of net zero carbon emissions by 2050. TotalEnergies of France and Royal Dutch Shell are among those that have shown early interest in a potential bidding round for wind development rights.

John Bel Edwards, the Democratic governor of Louisiana, has said his state’s long experience in oil and gas gave it “a strategic advantage in developing offshore wind in the Gulf of Mexico.” The federal government envisages lease sales in the gulf by early 2023.

Yet gulf projects are likely to fall behind projects on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts in the wind development queue.

One reason is weaker wind speeds in the gulf and lower average electricity prices in Texas and Louisiana. A report from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory found that the “estimated cost of producing power from offshore wind at all GOM sites was above the required revenue opportunities,” unless costs continued to decline.

Then there are the gulf’s hurricanes. NREL said turbine engineering technology had “gaps” in the face of extremely high winds, though they were not insurmountable.

State policies also favour the US east and west coasts. Republican state officials in Texas, an oil and gas powerhouse which also boasts the nation’s largest land-based wind industry, have been mostly silent on the prospect of wind turbines off its coast. Governor Greg Abbott told UN secretary-general António Guterres to “pound sand” in response to a suggestion that Texas should further embrace its clean-energy potential.

Getting “Texas a little more on board” would make it a “much more interesting region” for developers given that the state has the country’s largest power market, said Lucas Stavole, an analyst at the consultancy Wood Mackenzie.

Meanwhile, eastern states such as New York have clean energy targets and subsidies for the emerging offshore wind industry and have already approved projects.

“If you are a project developer, a state that has renewable power mandates, as well as offshore wind specific targets, is going to be much more attractive than the Gulf of Mexico right now,” said Timothy Fox, vice-president at ClearView Energy, a consultancy. The Biden administration received a “tepid” response when it first solicited interest in gulf wind leases earlier this year, he added.

Still, some industry executives are optimistic that a wind power industry will eventually plant itself in America’s maritime oil hub.

“TotalEnergies is excited to participate in the future Gulf of Mexico wind energy area leases,” David Foulon, head of the company’s US offshore wind business, wrote to regulators. “Our expertise in offshore operations and maintenance is what will make offshore wind a success.”

James Cotter, Shell’s Americas offshore wind manager, told a conference in August that the gulf was “already an energy basin and it will stay that,” with opportunities to repurpose ageing oil infrastructure for wind projects. Shell has one of the largest networks of offshore oil assets in the region.

David Hardy, North America president for Orsted, the world’s largest offshore wind developer which is developing a pair of projects in the US north-east, told a congressional hearing in October that the gulf could become viable for wind generation.

“The wind speeds are lower there, but the turbine technologies continue to evolve just like for onshore wind,” he said. “The original turbines were developed for the North Sea where the wind speeds are higher, but as we move to lower wind speeds, the turbine technology . . . can be built to support those low speed winds.”

Hardy pointed out that even without new wind farms, the gulf region’s deep experience in the offshore oil industry had made it an essential part of the emerging domestic supply chain for US offshore wind farms. Shipyards and fabricators that usually turn out massive oil platforms are now assembling offshore wind kit.

Louisiana-based Gulf Island Fabrication built foundations for Orsted’s Block Island wind project off Rhode Island. Richard Heo, Gulf Island chief executive, said the work was part of a strategic shift aimed at lessening its reliance on the offshore oil business.

The Virginia-based electric utility Dominion has ordered a wind turbine installation vessel in Brownsville, Texas, a coastal hub for the offshore oil industry.

Stavole, the Wood Mackenzie analyst, says it is only a matter of time before wind turbines themselves go up in the gulf.

“What it comes down to is, let’s see these offshore farms on the east coast really take off in the next couple of years and then you start looking at less desirable areas,” he said. “It’s going to happen at some point — but will it happen by 2030 or 2040? We’ll see. Moving forward on the leasing is certainly a positive sign.”

Twice weekly newsletter

Energy is the world’s indispensable business and Energy Source is its newsletter. Every Tuesday and Thursday, direct to your inbox, Energy Source brings you essential news, forward-thinking analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here.

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.