UK steel industry warns it needs state aid to survive green transition

In the hazy gloom of a cavernous building at Tata Steel’s sprawling Port Talbot complex in south Wales, streams of molten iron come hissing out of one of the site’s two blast furnaces.

The scene, which has been at the heart of the steelmaking process here for decades, is now under threat as the industry looks to lower carbon emissions. Dean Cartwright, works manager for coke, sinter and iron, who has been at the plant for 24 years, said locals still wanted to work at the area’s biggest employer but were increasingly aware it was facing a serious challenge.

“There is lots of talk about decarbonisation. People automatically think, will I still have a job,” Cartwright explained.

Tata is weighing the hugely expensive shift of moving Port Talbot — the UK’s biggest steelmaking plant — to a less-polluting way of making steel, a transformation that the company said would need government support.

They are not alone. Tata Steel UK, a subsidiary of the Indian conglomerate that owns Port Talbot, and China’s Jingye, the owner of British Steel, the UK’s second-largest producer at Scunthorpe in Lincolnshire, are both in talks with the government over financial support. They have warned that without taxpayer help they could be forced to close their operations, leaving the UK as the only large economy without primary, or virgin, steel production.

The companies, which together operate Britain’s last four blast furnaces, want help to cover the huge cost of shifting from traditional, energy-intensive steelmaking to greener alternatives to reduce their carbon emissions. Analysts have estimated that it would cost about £2bn to decarbonise Port Talbot alone. Jingye has also asked for short-term aid to help its business through the recent jump in energy and carbon prices.

More than 4,000 jobs are at stake at Port Talbot and another 4,000 at British Steel, most of them at Scunthorpe, with thousands more at risk in the supply chain.

Industry executives have warned of wider consequences if the steel plants close: without low-carbon domestic steel, Britain would not have its own source of a basic material needed to reduce emissions in other industries, such as construction.

Port Talbot produces 3.6mn tonnes of steel annually and supplies key sectors, including carmaking and construction. The industry makes up just 0.1 per cent of Britain’s total economic output but it provides highly skilled manufacturing jobs, with wages above the national average.

“It’s not only about the decarbonisation of steel,” said Rajesh Nair, chief operating officer at Tata Steel UK, who declined to comment on the talks with the government. “It’s a story that should be on the table as a country and an economy: how do we want to progress the economy in the future? To decarbonise other industries . . . you need to decarbonise the steel industry,” he added.

The steel sector is the UK’s biggest industrial emitter of carbon dioxide and the Climate Change Committee, the government’s independent advisory group, has said it needs to be “near zero” emissions by 2035 if the government is to meet its pledge to reach net zero by 2050.

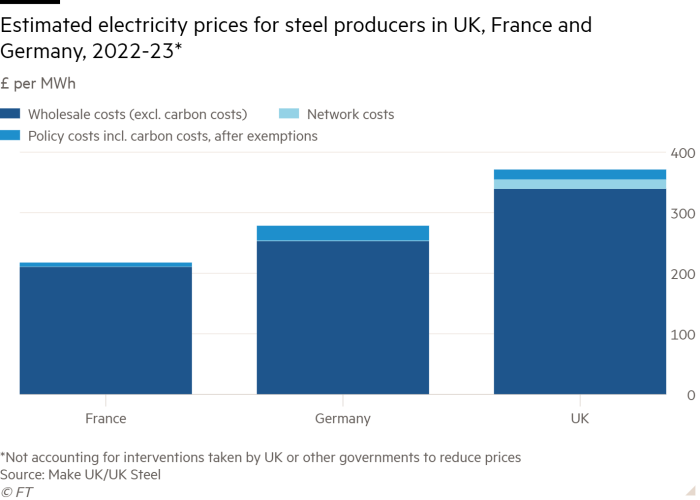

As well as state aid, executives are pushing for certainty of policy through the transition, as well as clarity on the future supply of affordable green electricity and green hydrogen before investing. Trade union representatives point to the significant support that other European governments, such as Germany and France, have committed.

Gareth Stace, director-general of trade body UK Steel, said that “cost competitive electricity to steel sites, reform of our carbon pricing system . . . and targeted support for capital investments in the new forms of steel production” were among the policy interventions that are needed to put the sector on to a sustainable footing.

Ministers, however, face a difficult choice, said Chris McDonald of the Materials Processing Institute, an industry research group. “If they say no and the blast furnaces close, the UK will be the only modern economy without its own steelmaking.”

“If they say yes, will the money be used to prop up these blast furnaces when the money should be spent on a green transition? The option of letting the steel industry go to the wall is not an option,” he added.

Critics of direct intervention point out that Tata Steel UK posted a pre-tax profit of £82mn in the 12 months to the end of March. But industry analysts said the profit was the company’s first in 13 years of ownership and driven by record global steel prices, which have since dropped.

Tata Steel’s chief executive, T V Narendran, warned that time was running short to make the business sustainable given high energy prices. To help Port Talbot to transition to alternative technologies and remain viable would “require significant investment and policy support from the government”, he said. An agreement on support had become more urgent as Tata Steel UK faced “significant challenges as a result of high energy costs”, he added.

British Steel declined to comment but confirmed it was in talks with the government to “overcome the global challenges we currently face”. The company met with Jacob Rees-Mogg, the previous business secretary who has since been replaced by Grant Shapps, twice last month.

In a statement, the government said it recognised “the critical role the steel industry plays in all areas of the UK economy”, adding that its support for the sector’s low-carbon transition included access to more than £1bn to help with energy efficiency, low carbon infrastructure and research and development.

Although Tata has invested in energy efficiency measures at Port Talbot, neither the Indian group nor Jingye have publicly committed to a particular decarbonisation path. Options on the table range from capturing the emissions from existing operations and storing them, the greater use of electric arc furnaces that melt down scrap steel, to using hydrogen or natural gas instead of coking coal to extract iron from iron ore.

All methods, however, have challenges. Steel produced in electric arc furnaces, which are used by some of Britain’s smaller producers including Celsa and Liberty Steel, cannot be used for some important applications. Job losses would be inevitable, especially as facilities such as coke ovens would no longer be needed.

Experts said the route that would allow a more gradual transition would be to use natural gas or hydrogen instead of coke — to make so-called direct reduced iron. DRI is compatible with both blast furnaces and electric arc furnaces.

If the UK is to meet its net zero target both companies need to be able to take a decision soon to protect the thousands of highly skilled jobs for the next generation of steelworkers. “Once you’re in, it’s a fantastic place to work,” said Cartwright.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.