Thinking of eating bugs to save the planet? Tribal communities in India have been doing it for centuries

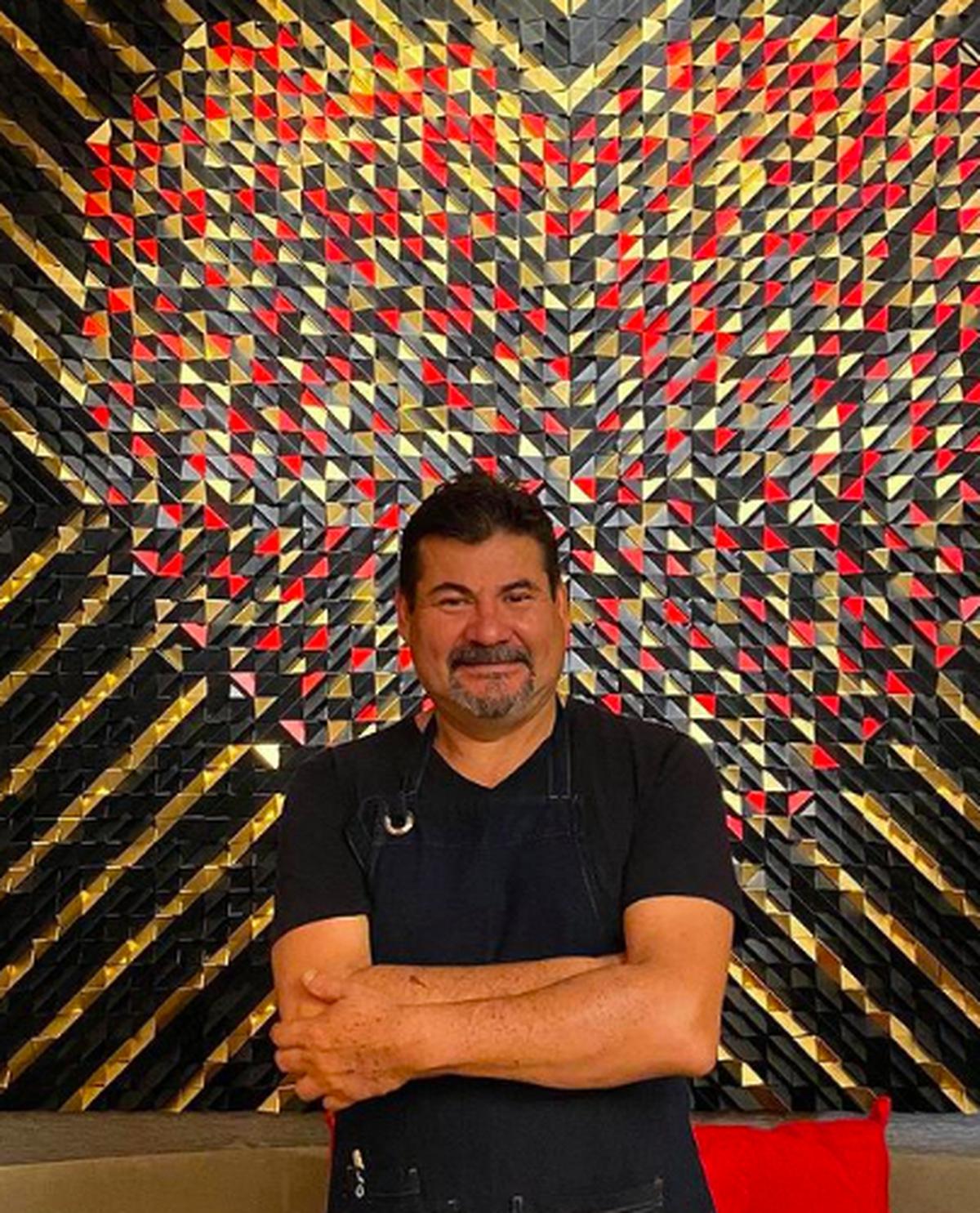

In a city renowned for its food, Mexican chef Alejandro Ruiz Olmedo shines extra bright. He is a sort of culinary ambassador for Oaxaca and his restaurant Casa Oaxaca has been on the 50 Best Restaurants in Mexico list three years in a row.

Mexican chef Alejandro Ruiz Olmedo.

| Photo Credit:

www.instagram.com/chef.alexruiz

Every dish is a work of art and the tostada I order is no exception. It looks like a garden exploding with deep reds, spring greens and chocolate browns. Except this is no ordinary tostada. It is a tostada de insectos, a crisp corn shell topped with chicatana ants, chapuline grasshoppers and agave worms around swirls of guacamole and herbs.

Casa Oaxaca’s ‘tostada de insectos’, a crisp corn shell topped with chicatana ants, chapuline grasshoppers and agave worms around swirls of guacamole and herbs.

| Photo Credit:

Sandip Roy

It is crunchy, and savoury with little sour notes from the ants. And it pairs wonderfully with a mezcal sour cocktail.

“That’s very brave of you,” says a local. There is indeed always an element of daring and adventure when eating bugs. Insects are slowly becoming haute cuisine, proudly part of the menu at upscale restaurants like Casa Oaxaca. The salsa freshly made at the table comes with the option of ground-up chapuline grasshoppers.

With human population estimated to touch 9.8 billion by 2050, we are told we cannot continue eating beef, mutton and chicken the way we do. The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) says we all need to eat more bugs to meet our protein needs. The European Union has okayed powdered migratory locusts and dried mealworms as food. Eating insects isn’t just for Instagram likes, it’s sort of an ecological badge of honour. Conquer your gag reflex and save the planet. Barclays estimates the edible insects market will grow to $6.3 billion by 2030.

Tansha Vohra of ‘The Boochi Project’.

| Photo Credit:

serendipityarts.org

That trend might not have yet reached a fancy restaurant in Mumbai or Bengaluru but there are ventures like The Boochi Project in India taking six-legged baby steps into that brave new world.

Tansha Vohra who runs it tells me there are over 200 edible insects in India, and a start-up called Insectify is trying to use black fly larvae, which is super high in fibre, for animal food. “We’re in the process of making a miso out of black fly larvae,” she says.

Too embarrassed to eat

Yet, Vohra is very aware that this new-found excitement about insects as food harkens back to a very old insect eating culture. This is not something virtue-signalling eco-warriors in California or Berlin can teach us. Indians have been eating insects for centuries. Srishta Aparna Pallavi, who writes about indigenous people and their traditions, tells me that tribal people have long relied on, and enjoyed, their weaver ants, termites and palm grub.

But even while the FAO tells the western world to think of insects as sustainable protein, Indian tribals have been taught that their ancient traditions are primitive and disgusting, something only very poor people do. In a TED Talk, she describes how a tribal person hid the insects they were eating from her, too embarrassed to admit to not just eating bugs, but liking them. Some Adivasis even scolded her for her interest in insects, wondering why she was trying to drag them backwards to a past they’d been told was shameful.

So, she would probably look at my tostada de insectos with mixed feelings. “It is a little scary when things get carried out of context because when I think of insect foods, I think of tribal knowledge and tribal ownership,” she says. “I would like for insect knowledge that exists with the Adivasis to be revived in a way that Adivasis can retain ownership.”

A vendor sells grasshoppers at a market in Oaxaca, Mexico.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Oaxaca in southern Mexico is one of the most beautiful towns in the country. Its cobbled streets and brightly coloured houses are a delight to explore. Its food is legendary with seven kinds of mole sauce being served in one restaurant alone. Its chocolate is famous. But this is also a part of Mexico that’s home to the indigenes. Sixteen of Mexico’s 68 indigenous groups live in this province which along with Chiapas is one of the poorest. As tourists roam its beautiful cafes and chic mezcal bars, one sees indigenous people on the streets selling knick knacks or playing music for a few pesos.

Raul, who took us on a walking tour of the city, belongs to one of those communities. He says he grew up in a part of Mexico where 10 years ago they had no running water, no toilets and barely a chair to sit on. Now it amuses him to see tourist reactions as he talks about swanky restaurants in Oaxaca that serve worms and ants.

“They will tell you it is the food of the future,” he says. “But really, it’s the food of our past.”

The writer is the author of ‘Don’t Let Him Know’, and likes to let everyone know about his opinions whether asked or not.

For all the latest Life Style News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.