They added an ADU that’s ‘not too big’ and ‘not too small’ to their L.A. fixer-upper

Standing at the front of Danielle Rago and Darren Hochberg’s home in Larchmont Village, where a concrete sidewalk welcomes you, the ordinary path becomes something extraordinary as it takes you on a journey from the street, through the house, to where the sidewalk ends — an accessory dwelling unit (ADU) in the backyard.

The 620-square-foot ADU can be glimpsed through the windows of the main house. Together, the two buildings — home and ADU — now form an indoor-outdoor family compound.

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

As nearly 3–year-old Oliver Hochberg races down the smooth path toward the enclosed backyard and ADU, it’s as though he is personifying Shel Silverstein’s beloved poem that promises magic “for the children, they mark, and the children, they know the place where the sidewalk ends.”

But it wasn’t always this way.

“Calling all handy families, investors, and developers!” read the listing for the crumbling three-bedroom, two-bathroom home just a few blocks from Larchmont Boulevard’s main street.

Those words, followed by a bonus sales pitch: “There is also a detached structure that would make a perfect creative space, playroom, or mother-in-law suite. Bring your contractor and your imagination and create the space that you have been dreaming about.”

The front of the 1929 house before it was remodeled. “I like that it needed a lot of love,” says homeowner Danielle Rago. “I was excited by the prospect of creating an unexpected family compound that would complement the other homes on the street.”

(Injinash Unshin)

Today, the geometric facade of the house stands out but doesn’t overwhelm the other homes on the street.

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

The listing caught the attention of Rago and Hochberg, who had been dreaming of buying a home in the popular neighborhood known for its tree-lined streets, quaint single-family homes, and easy access to Hollywood and downtown Los Angeles.

With the number of ADU permits issued in California skyrocketing as thousands of homeowners add ADUs to their single-family lots, it’s not surprising the listing would emphasize the possibility of converting the garage into an ADU.

The built-in desk inside the ADU can be opened or closed, depending on the couple’s work-from-home needs. “I want to spend as much time at home with the kids as I can while they are little,” Danielle Rago says.

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

It certainly appealed to Rago, who has a background in architecture and is the co-founder of This X That, an agency that represents progressive architects. “I like that it needed a lot of love,” says the 39-year-old. “I was excited by the prospect of creating an unexpected family compound that would complement the other homes on the street.”

Eight years ago the family — which now includes 3-month-old Julian and Oliver — purchased a rundown Spanish home in the Fairfax District. After renovating the home, however, they found themselves weary of bustling Melrose Boulevard and were contemplating their next big project. “We were itching to move to Larchmont Village because we were thinking about starting a family,” says Rago, citing the neighborhood’s small-town vibe.

A concrete sidewalk travels from the curb, through the house, to the ADU.

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

They loved the neighborhood but like so many couples in Los Angeles could not afford the homes that were available. “Everything was so expensive,” Rago says with a sigh. “We had to buy a home that needed a lot of TLC.”

Using the profits from the sale of their remodeled Fairfax District home, the couple purchased the bungalow in 2019 and reached out to designers Claus Benjamin Freyinger and Andrew Holder of the Los Angeles firm the Los Angeles Design Group (LADG) to help them rethink the entire property.

The bedroom and bathroom of the ADU are spare and peaceful (and popular with relatives).

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Having worked with them professionally, Rago felt the designers had the right mindset to help them create an experimental compound that would accommodate not just their family, but their extended families for years to come. (The couple paid for the firm’s design services and received no discounts in exchange for Rago’s professional work for the company.)

From Day One, the couple knew they wanted to convert the garage into an ADU, not to bring in extra income to help pay the mortgage, but rather as a way to take full advantage of the site.

The problem with ADUs, says Freyinger as he motions to the ADU on view through the living room’s dramatic pivoting window, is “they don’t always address the entire parcel of land.” Or worse, they sit vacant.

“We wanted to preserve the use of the whole site,” he continues. “This home and ADU are very ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears’: Not too big. Not too small.” In other words: just right.

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Gone are the days of congregating around a hearth or a fireplace, Freyinger says. Today’s homes are about creating welcoming spaces where people can connect with one another. So the designers added additions to the front and back of the dwelling and cut the house into four quadrants divided by two running sidewalks that run west to east and north to south. Three small bedrooms are placed at the front of the house, while the larger communal spaces are placed at the rear of the house.

Today, the 1,426-square-foot nondescript home has morphed into a 1,950-square-foot contemporary home. The kitchen, considered the household’s nucleus, soars into double-height OSB-paneled volumes. Overlapping, wedge-shaped roofs extend to provide shade over outdoor living areas, and a sunny living room overlooks the 4-foot-deep pool and ADU.

The 620-square-foot ADU, which shrewdly includes a storage-lined breezeway that can accommodate the family’s sports equipment, toys, strollers and storage bins, cost $315,150 and includes one bedroom and a bathroom.

A kitchenette was installed at the front of the ADU so that it faces the yard. When the folding glass door is open, the kitchen becomes a part of the outdoor area.

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

In an inventive move, for outdoor entertaining the designers installed a kitchenette at the front of the ADU so that it faces the yard. When the folding glass door is open, the kitchen becomes a part of the outdoor area, which “really brings the ADU to life,” says Hochman, who is 39 and works in finance.

On the other side of the kitchenette, facing the living room, there is a built-in desk that can be opened or closed, depending on the couple’s work-from-home needs.

Due to supply chain issues during the pandemic, Rago says they were forced to “make interesting decisions that brought a new dimension to the house.” In the kitchen of the main house, for example, they installed textured plaster ceilings when plywood was scarce. Likewise, the cabinets are composed of conventional whitewashed OSB panels with a pickled finish.

Left: The living room of the ADU. Right: Oliver follows the concrete path to the ADU.

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

To save money in the ADU, they added simple concrete floors and purchased a folding glass door from Brea-based Win-Dor at a fraction of the cost of higher-end products like Fleetwood or NanaWall. The kitchenette features inexpensive OSB panels and porcelain countertops instead of quartz or granite. “We stepped it down a notch in the ADU,” Rago says, “but it still reads consistently with the main house.”

The couple, who met in the Poconos when they were 8-year-olds, view the ADU as an extension of the house. They occupy it regularly while working from home or hosting family.

Tour this ADU

The home and ADU will be open to the public in conjunction with the AIA LA’s 2023 Arch Tour Fest at 9:30 a.m. May 19. Tickets, $20 to $55.

A view of the ADU from the home’s new living room. The designers shrewdly added storage alongside the breezeway, left.

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

“I want to spend as much time at home with the kids as I can while they are little,” Rago says.

Rago and Hochberg’s compound is all about being together and the joy that dwells at the end of the sidewalk. It provides an indoor-outdoor experience where their kids can roam free in a drought-tolerant garden filled with sages, California poppies and grevillea, and they can spend time with the ones they love.

“We wanted a space for our family, who are all on the East Coast, so that they can come to visit us and our kids,” Rago says. “I wanted them to be able to stay for a week or two and feel like they are in their own home and not looking into our space and vice versa. Now, we can’t get rid of them,” she jokes.

The ADU may serve as an extension of the main house, but it also demonstrates, through its use of conventional materials and experimental architecture, that it’s possible to “chip away at the identification of the single-family home,” with its “conservative notions of architecture and the family,” says the LADG‘s co-principal Andrew Holder.

Perhaps most impressive is the designers’ ability to create something new while maintaining the small town feel of the neighborhood. From the street, the geometric façade stands out, but it doesn’t overwhelm. And at the end of the sidewalk? Magic.

The rear of the Larchmont Village home before it was remodeled.

(Injinash Unshin)

Danielle Rago and Darren Hochberg, their children, Oliver and Julian Hochberg, and their Maltese pup, Melrose.

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

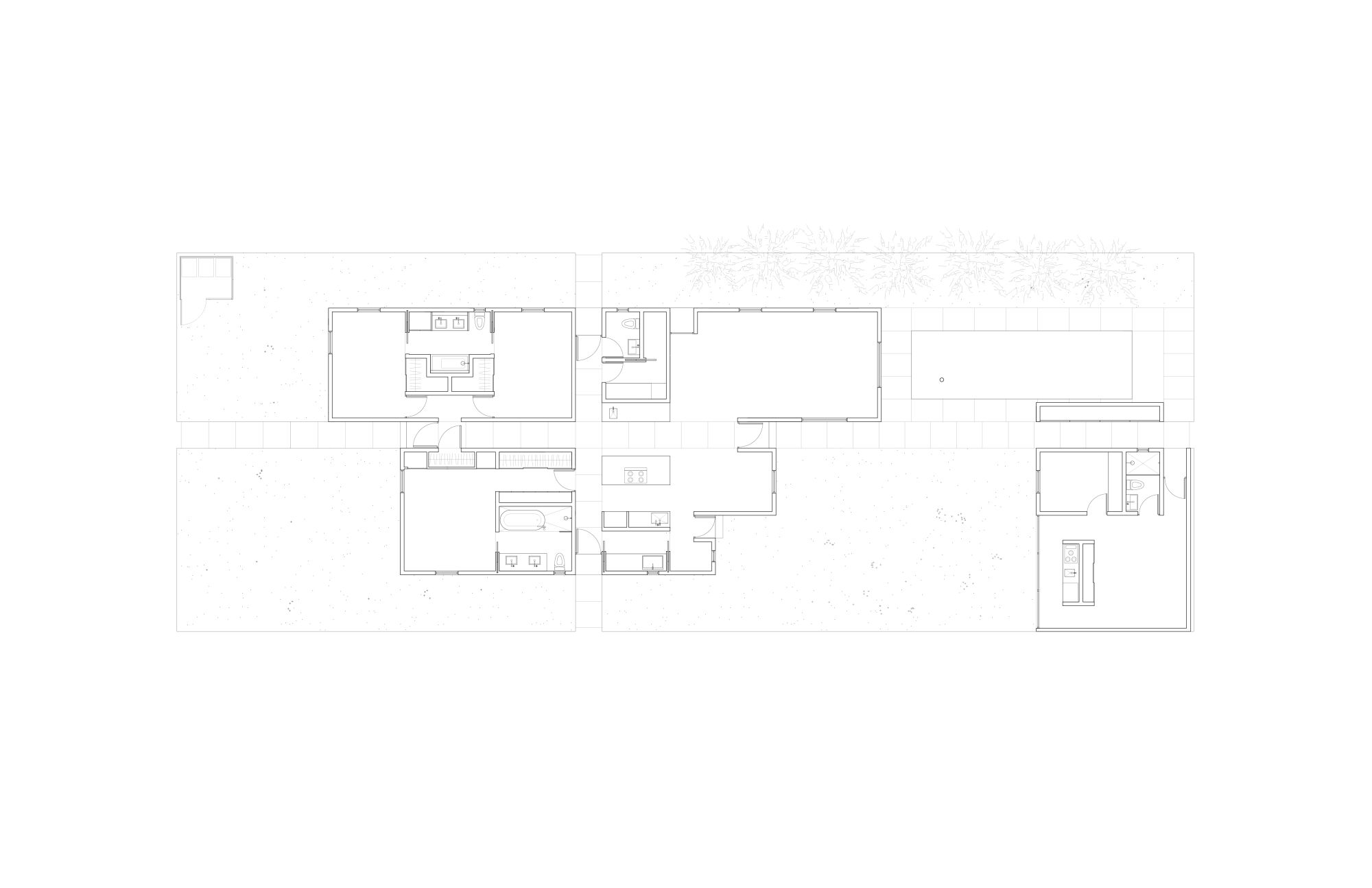

The plans for the home and ADU.

(The LADG)

For all the latest Life Style News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.