The Spac machine sputters back to life after dramatic meltdown

Before Marc Bell went into business launching satellites, he enjoyed a lucrative career at the outer reaches of professional finance.

Over 30 years, he has bought stakes in pornographic magazines and pizza parlours, produced Tony Award-winning musicals and earned enough money that he once lived in a Florida mansion whose lavish decor included a full-scale replica of the bridge of the Starship Enterprise.

Last month Bell struck a $1.6bn deal to publicly list Terran Orbital, an operator of small observation satellites he founded eight years ago. To do so, it will merge with a special-purpose acquisition company, or Spac — a shell company that has raised money to complete a transaction.

The largest investor in the transaction is Daniel Staton, an old friend with whom Bell launched FriendFinder, a network of social media websites founded in 2003. Now a director of Terran Orbital, Staton agreed to invest $30m through a privately arranged fundraising that makes up more than half of the total $50m backers such as Lockheed Martin are putting into the deal.

The catch: Staton will receive his $30m back over a period of four years through quarterly outlays in cash and stock. While most investors in similar deals receive only shares, Staton’s “payment obligation” will in effect make his investment a free option on the company’s future earnings.

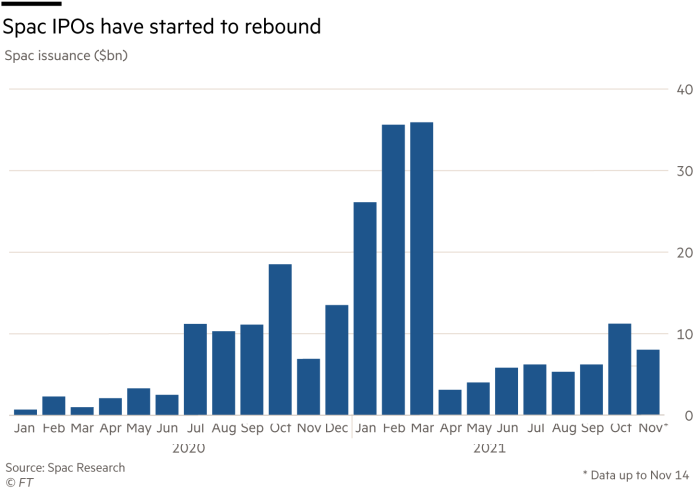

The Wall Street assembly line for new Spacs has started cranking up again following six months of pain, as a series of scandals and regulatory scrutiny deflated a pandemic-era boom that briefly became the dominant story in American capital markets.

The new round of deals has even included one last month involving Donald Trump, which sparked frenzied trading in certain corners of the market.

Spac sponsors hope that the new signs of life herald a maturing market. Some have drawn analogies with the junk bond market, which went through a frenzied boom period followed by scandal in the 1980s before eventually becoming an integral part of the modern financial system.

But the recent flurry of deals suggests a different, more constrained reality. With many of the institutions which were once eager to back Spacs now sitting on the sidelines, the Terran case shows how dealmakers are being forced to lean on a smaller group of initial investors who can then extract better terms.

For critics, deals like the Terran merger are examples of the flaws that still characterise the Spac market, which they argue is lopsided toward financial sponsors and other insiders. Terran declined to comment on the deal.

In recent months, investors, legislators and regulators have begun taking stock of the Spac boom and many have reached the same conclusion: that the market tends to benefit insiders by enticing investors to make speculative bets on companies that otherwise would not be public.

“There is a wild amount of froth,” says Nathaniel Anderson, founder of short seller Hindenburg Research, which has targeted multiple companies that went public through Spacs. “There are a tremendous amount of companies that are intrinsically worthless that are sporting multibillion-dollar valuations. It has become commonplace now.”

From boom to bust

The pandemic created the conditions for a boom in Spacs, which date back to the 1990s.

With emergency rate cuts during the crisis leaving investors desperately searching for yield, hedge funds and other investors began pouring record amounts of capital into blank-cheque company offerings. Spacs then take that money and look for a company that can be introduced to public markets through a merger.

Early successes, such as DraftKings, the US betting group, and Virgin Galactic, the space tourism company, also helped give credence to the idea that there were countless hidden gems in private markets waiting to go public.

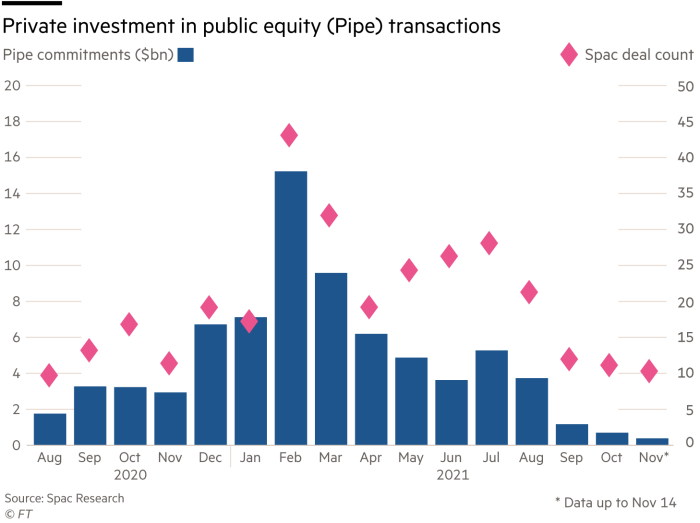

But the market really started to take off in late 2020 as demand for the structures ramped up and executives saw how lucrative Spacs could be. Adding fuel to the fire were a group of institutional investors who agreed to partake in deals through so-called private investment in public equity transactions, known as Pipes.

Under these agreements, investors are invited to sign a non-disclosure agreement and shown the target company before a deal has been announced. If they decide to participate in the transaction, they usually purchase shares at $10 — the same price at which the Spac raises cash — giving them a significant stake in the new company once it goes public.

Pipes have transformed the Spac market and helped dozens of relatively immature companies raise billions of dollars in funding. As well as providing extra cash, they add credibility to the company and its valuation in what is seen as a seal of approval from Wall Street.

Investors ploughed $30bn into Pipe deals during the first three months this year, according to the data provider Dealogic. The total more than doubled the volume from the previous quarter.

This coincided with a frenzied period of dealmaking and fundraising. Within the first 10 weeks of the year, blank-cheque companies had already surpassed 2020’s fundraising record and signed $109bn worth of deals. Even rumours of a pending transaction were enough to send shares in the shell companies soaring.

This froth has fuelled concerns that some of the companies that struck deals at the height of Spac fever were not yet ready to go public or did so at egregious valuations. A retreat from institutional investors over the past six months has done little to assuage those fears, with many pausing to take stock of how their portfolios have performed.

Pipe volumes are now down to a monthly average of approximately $4bn and much of that cash is now coming from insiders rather than big mutual or sovereign wealth funds, according to market participants. The shift means that a tighter band of executives and investors are holding up the market, and setting themselves up to profit if sentiment turns.

“There are more insider buy-ins of these Pipes rather than broader large institutional book builds that participants would rather see,” says Joshua DuClos, a partner at Sidley Austin. “Some investors may have gotten over their skis and their books might have not turned out well this year,” he adds.

Performance has been a problem for many of the companies that agreed to go public through Spacs at the height of the boom.

A Financial Times analysis of data provided by Refinitiv shows that 65 per cent of deals completed in 2021 at a valuation above $1bn are trading below $10 – the price at which they were floated. All of the companies are trading below their stock market highs with some of them down by as much as 70 per cent.

“There were many companies that have, and I suspect many that will be, taken to the public via a Spac that are not ready,” Betsy Cohen, a veteran sponsor who has set up multiple blank-cheque companies, said at the FT’s Dealmakers conference earlier this month.

Spac stumbles

The Spac boom had reached its peak when Archer Aviation, a flying taxi start-up, agreed in February to combine with a blank-cheque company led by investment banker Ken Moelis at an enterprise value of $2.7bn.

Like many other electric vehicle companies in its cohort, Archer was yet to book any revenue or make a commercially viable product, but said it had plans to unveil its prototype later this year. The company projected that its revenue would grow from $42m in 2024 to $12.3bn six years later.

Archer raised $600m through a Pipe from investors such as United Airlines and Mubadala Capital, a subsidiary of Abu Dhabi’s second-largest sovereign wealth fund. However, five months later, it was forced to cut its valuation by $1bn.

Shares in the Palo Alto, California-based company are down 65 per cent from their February peak to less than $6. Still, the stock award allocated to the sponsor for a nominal sum of $25,000, known as a “promote”, is worth approximately $75m. Archer’s co-founders, Brett Adcock and Adam Goldstein, are sitting on a combined $220m fortune after each were awarded 20m shares as part of the deal.

Some companies have performed so poorly that they’re being bought at discount rates by rivals.

Metromile, an auto insurance company that reached a market value of $2.5bn following a Spac deal in February, sold to the home insurer Lemonade in an all-stock deal for one-fifth of that total this month.

Chamath Palihapitiya, a serial Spac sponsor with 1.5m Twitter followers, and other backers had invested $170m in Metromile as it went public with an initial value of almost $1bn. Nearly all of the Spac’s investors opted to remain shareholders in the combined company.

Since then, the company has struggled to live up to expectations.

Metromile projected its active insurance policies would increase by 40 per cent this year to nearly 130,000. Yet policies shrank by more than 600 in the second quarter, a decline the company attributed to “greater-than-expected cancellations” due to Covid-19, and “lifestyle changes”.

By the time Metromile announced the sale to Lemonade, its shares had fallen by as much as 80 per cent to a low of $3. The sponsors of the Spac that took the company public still stood to receive approximately $30m worth of Lemonade stock, after investing just $5.4m.

Despite waning enthusiasm for Spacs among investors, there are key market players who have every incentive to keep the party going. These deals have made multimillionaires and, on occasion, billionaires of the executives backing them.

Sponsors that have completed deals since 2020 were entitled to as much as $19.6bn in shares in the merged companies, having invested $1.8bn upfront to form the Spacs, according to an FT analysis of Spac Research data based on current market prices.

While venture capital investments can take a decade or more to pay similar dividends, successful sponsors can reap huge rewards as soon as two or three years after raising a Spac.

At the high trading points for each of the Spac deals completed since 2020, the total value of the sponsor shares would have swelled to as much as $37bn, according to the analysis.

The data does not account for concessions that sponsors sometimes make before finalising Spac mergers, and sponsors often must wait years or meet price targets before receiving the full value of their shares.

However, the total illustrates how relatively small investments can create large windfalls for Spac founders, incentivising their pursuit of any viable deal. The total also does not account for potentially lucrative equity warrants that sponsors receive for their upfront investment.

A recent academic study concluded that “companies that provide high revenue forecasts in their investor presentations attract significantly more retail investors and that these same firms underperform in the long term”.

“The sponsors get the biggest lion share of any sort of value,” says Michael Dambra, an associate professor at the University of Buffalo school of management who was the lead author of the study.

Lawmakers catch up

Some sponsors argue that these examples are growing pains and that the pullback from both retail and institutional investors is evidence that the market is self-correcting.

Several have drawn comparisons to the early days of the junk bond market or things like real estate investment trusts and business development companies, which also went through boom and bust cycles.

“This is no different than REITs or BDCs,” says Jack Leeney, a venture capitalist who has sponsored a Spac. “They all went through the roof when they got popular and then they normalised and the quality was established. Now they’re just like regular old boring capital markets products.”

“The first few years of the high-yield market were all over the place. The leverage was too high, investors didn’t know what they were buying and a lot of things should not have happened and there was a lot of pain afterwards,” Andrea Bonomi, the founder of private equity firm Investindustrial, said at the FT conference. “But fast forward a number of years, now it’s a good instrument.”

Yet in at least some quarters, there are some signs that sentiment is turning against Spacs. Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, Wall Street’s most prestigious banks, have begun steering their blue-chip clients away from Spacs in favour of traditional IPOs and direct listings, said two Spac sponsors. Morgan Stanley declined to comment, and Goldman Sachs did not respond to a request for comment.

The lucrative rewards enjoyed by Spac sponsors have captured the attention of lawmakers, most notably Senator Elizabeth Warren. In September, she and three other Democrats sent letters to a group of executives behind some of the most popular transactions raising concerns about “misaligned incentives between Spacs’ creators and early investors on the one hand, and retail investors on the other”.

Banks, which have benefited handsomely from helping executives raise Spacs as well as advising on their deals, have also been asked to provide information regarding their role by the Securities and Exchange Commission.

IPO underwriters have made $5.8bn in fees from Spacs since 2020, according to Refinitiv data. Citi, the most active underwriter, made $740m for working on almost 140 IPOs during that period. Additionally, banks raked in $2bn for advising companies on Spac mergers and Pipe financings, Refinifiv data shows.

At the same time, lawyers who also act as advisers on Spac deals and listings, have sought to protect the market from litigation. A high-profile claim against Pershing Square Tontine Holdings, the vehicle launched by billionaire hedge fund manager Bill Ackman, prompted dozens of the largest US law firms to band together and respond via a public letter.

The highly unusual manoeuvre sought to dispel claims that Spacs operate as investment companies without registering as such. Signatories to the letter included the top three legal advisers on blank-cheque mergers, White & Case, Kirkland & Ellis and Weil Gotshal & Manges.

Perhaps the greatest sign of a comeback is the enthusiasm with which Digital World Acquisition Corporation was met. Shares in the Spac climbed by more than 800 per cent after it announced plans to merge with Trump Media & Technology Group, a company set up by former US president Donald Trump in a bid to create a new social media platform.

The surge in the Spac’s shares appeared to be based on hype alone. A presentation accompanying the deal had little detail of the company’s operations or Truth Social, its social media app, other than to say it would “stand up to the tyranny of Big Tech”.

The real test will come as Trump and Patrick Orlando, the former Deutsche Bank executive behind the Spac, try to raise money from institutional investors through a Pipe. The former president may well follow in Bell’s footsteps, a fellow New York transplant in Florida, and tap his business associates for help.

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.