The night shift is back as Americans work overtime to clear backlogs

Trevor Bidelman typically works from 7am to 3pm at a Kellogg cereal plant in Battle Creek, Michigan. But recently, he has been working late into the night four or five days a week.

“They walk up to you at about 2:55 and tell you that you’re stuck there until 11pm,” Bidelman says. “It’s to the point where it’s inhumane; we just became used to it.”

The late-night shifts, along with a two-tiered scheme for healthcare benefits, pushed 1,400 Kellogg workers across four states to launch a strike that is now in its fourth week.

Manufacturers and fulfilment centres are desperate to find workers to fill a growing number of night shift positions, as they race to keep up with strong demand for both consumer packaged goods since the early days of the coronavirus crisis and supply chain crunches.

The ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles both switched to round-the-clock operations in an effort to clear container pile-ups. Walmart is extending its normal operating hours, FedEx is extending its pre-existing night-time work hours, and Target will raise the number of containers it moves at night by 10 per cent, according to the Biden administration.

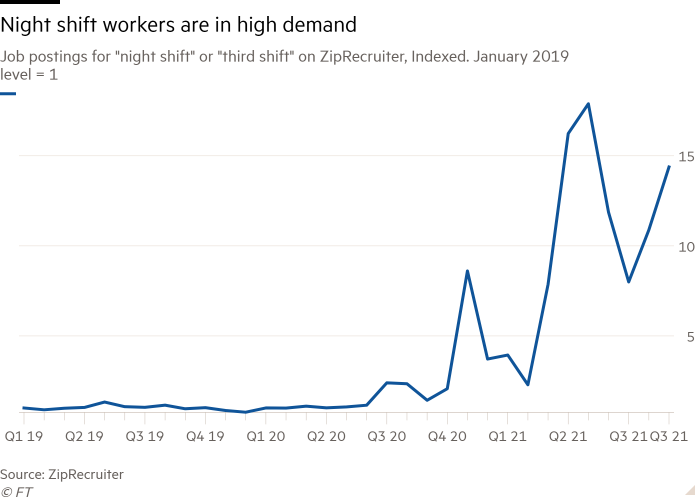

Night shift workers are in high demand as a result. The number of postings for roles that require overnight shifts on the jobs site ZipRecruiter was 14 times higher in September than was typical in the years before the pandemic as a result.

“Night shift job postings have simply exploded in 2021,” says ZipRecruiter’s chief economist, Julia Pollak. “There’s clearly been a huge spike in demand for workers prepared to work non-traditional shifts.”

A persistent labour shortage has made most hourly jobs difficult for employers to fill, especially those without flexible schedules that were already unpopular among workers when the labour market had more slack. For existing workers like Bidelman, that means a lot more forced overtime.

The American economy has relied on overnight shift work since the 1860s, when a campaign led by labour unions established a rotation of three crews working eight-hour shifts in factories. Still, three-quarters of workers prefer the traditional working hours of the day shift, according to staffing consultancy Shift work Solutions, over the second shift that starts around 4pm or the third shift that commences at midnight.

Some workers who take the third shift do so to balance caregiving responsibilities for their children or for wages that can be up to 15 per cent higher. But many see it as a stepping stone to in-demand roles earlier in the day, according to Shiftwork Solutions partner Jim Dillingham.

However, research shows that working the third shift violates the body’s natural circadian rhythm and puts workers at increased risk of intense fatigue and other health conditions including cancer and Covid-19. Workers’ trials on the third shift were chronicled in a hit song by The Commodores in 1985, but have since faded from popular culture. The labour department estimated in 2007 that about 20 per cent of workers worked something other than a regular daytime shift. In 2017 through 2018, when they last measured, 16 per cent of US workers worked non-daytime hours.

Just as the demand for third-shift labour began to take off again amid the ecommerce surge, the pandemic and the subsequent labour shortage have weakened many of the incentives to take the night shift, Dillingham said. Wages have risen across the board and many manufacturing plants and distribution centres are so short of staff that they are willing to hire more inexperienced employees for roles that were once highly sought after.

The crisis has increased demand for workers in some fields that have long required round-the-clock work, including nursing and policing, but the bulk of the spike can be attributed to a large expansion in warehousing work, according to ZipRecruiter.

Understaffing on late shifts and forced overtime have become pivotal factors in the recent wave of strikes that activists have dubbed “striketober.”

Gruelling 16-hour shifts and the short breaks between them became a sticking point for Hollywood crews that narrowly avoided a strike that would have shut down film and television production across the country earlier this month. Studios had been stretching out the length of shoots to make up for production time lost during Covid lockdowns, their union said. Their new contract guarantees time off between shifts and on weekends.

Bidelman hoped his colleagues could secure something similar when they resumed contract negotiations with Kellogg last week. The union rejected what Kellogg called its “last best final offer.” The company is now pressing the union to allow employees to vote on it.

Michael Innis-Jimenez, a labour historian at the University of Alabama, compares the conflict over the resurgence of the night shift with a similar one after the second world war. Factories operated with longer hours to supply the front for four years. But when they tried to maintain that pace after the war ended, without improving pay, a series of strikes ensued.

“My point with that is, this is not a war, it’s a pandemic. But there’s no greater cause here except for consumerism,” Innis-Jimenez says. “It really does take a toll on workers.”

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.