The global economy is very much in ‘here be dragons’ territory

Medieval mapmakers supposedly wrote “Here Be Dragons” (Hic Sunt Dracones in Latin) to indicate unexplored regions. However, there are in fact no surviving maps that show this, apart from a single 16th century globe. Somehow, the phrase remains well known today and the myth lives on, perhaps because it so aptly describes the combination of terror and wonder the unknown brings.

The global economy is very much in Here Be Dragons territory. Now that we can travel and congregate freely without masks and constant hand sanitising, it is tempting to forget how deeply the Covid pandemic continues to distort economic activity directly and indirectly. Directly, in the sense that China still maintains a policy of locking down wherever the virus appears, including entire cities. The indirect impact lingers in disrupted supply chains, changed consumption patterns and work behaviours, and massive fiscal stimulus in rich countries (especially the US) and resultant excess savings that still sustains spending.

The net result of this being the biggest global inflation surge in 40 years and a cost-of-living crisis in many parts of the world. Central banks have responded with aggressive interest rate hikes, especially the US Federal Reserve. Higher US rates and safe-haven flows have seen the dollar gain 18% on a trade-weighted basis this year, putting upward pressure on inflation and interest rates in all but a handful of countries, and tightening the screws on borrowers with dollar-denominated debt outside the US.

On top of all this, the brutal Russian invasion of Ukraine has seen energy prices go haywire as gas supplies are weaponised. Fighting climate change has taken a back seat as coal has become the go-to alternative. This moment has been aptly described as a polycrisis by economic historian Adam Tooze. Covid has worsened inequality in many countries, widened pre-existing socio-political divisions and generally made people angrier.

There has also been political fall-out, with more likely to come.

Terra incognito

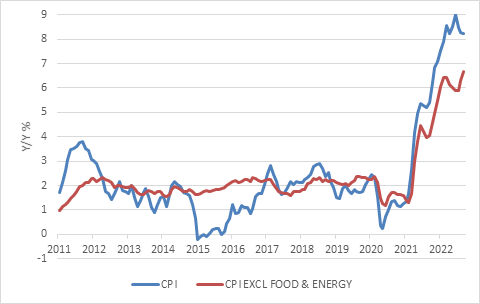

It will take time for a distorted economy to find its balance, and by implication, for inflation to settle. Last week provided a reminder of that as the latest US consumer price index release showed headline inflation at 8.2% year-on-year in September.

This is a marginally lower rate compared to the previous three months, but the core inflation rate that excludes food and fuel prices increased to 6.6%, the highest level since 1982 and twice the historical average of the series since 1957. And though it should ease in coming months, it is clearly a far way off from the Fed’s 2% target.

US consumer price inflation

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

The Fed and other central banks are not taking any chances, and this year has seen more of them hiking rates simultaneously than at any time previously. And while some are issuing warnings that this risks overdoing things, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) gave cover last week in its bi-annual World Economic Outlook, arguing that “front-loaded and aggressive monetary tightening” is warranted to avoid inflation expectations de-anchoring.

In other words, it sees the risk of not fighting inflation to be greater than the risk of overtightening since it can be painful to dislodge an inflationary psychology once it has become entrenched.

Labour markets in key developed economies are still unbalanced, with excess job openings and supply constrained by factors such as long Covid, early retirement, below-average migration and changing attitudes to work (the “Great Resignation”). Tight labour markets can give rise to wage-price spirals and unmoored inflation expectations in the view of the IMF and many central banks, justifying further rate increases.

The IMF’s forecasts point to weaker growth, elevated inflation, and risks that remain “unusually large”.

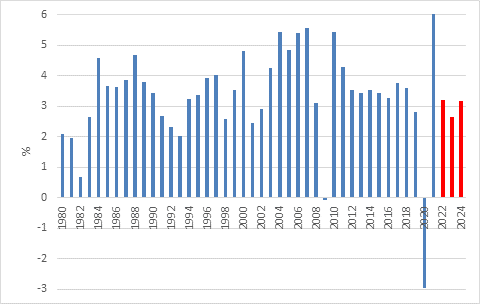

It expects global growth to slow from 6% in 2021 to 3.2% in 2022 and 2.7% in 2023. The average global expansion since the IMF started measuring it in 1980 was 3.6%. Global inflation is forecast to rise from 4.7% in 2021 to 8.8% in 2022, declining to 6.5% in 2023.

Real global economic growth with forecast

Source: International Monetary Fund

In terms of key economies, US growth is expected to slow markedly from 5.4% last year and 1.6% this year to only 1% in 2023. Given the gas crisis, Italy and Germany are forecast to contract next year, while the UK will stagnate. The IMF makes it clear that these forecasts are much more likely to be too optimistic than too pessimistic.

For the first time, the IMF has explicitly warned that China’s worsening property market carries substantial spill-over risks and will weigh on economic growth. It expects the Chinese economy to only expand by 3.2% this year and 4.4% next year, well below Beijing’s 5.5% target and the blistering growth many have come to expect from the world’s second largest economy.

Rapid tightening

Central to all the gloomy forecasts is the unprecedented pace of monetary tightening taking place currently. In some ways it is the mirror image of the stimulus that was unleashed in 2020 the enemy shifting from deflation to inflation in the space of the past 24 months.

There have been big interest rate cycles in the past, but never have so many central banks hiked so much at the same time.

The world economy has also never been so deeply indebted across public and private sectors and markets have never had to be weaned off central bank-provided liquidity at quite such a scale as quantitative tightening gets underway.

The chaos in UK bond markets is an example of how quickly things can unravel in such a difficult environment. The UK might seem like a unique case of reckless politicians doing irresponsible things, but there is no shortage of reckless politicians in the world, nor was there a shortage of reckless financial behaviour prior to this year. The consolation is that there hasn’t been wild excess in traditional banking activity as well as lending to households and corporates. These are the obvious places to look (obvious only after the 2008 financial crisis) but that doesn’t mean there aren’t risks hidden in murkier corners of the financial world.

The next question is what the economic impact of these blow-ups will be? When bitcoin or ARK crashed, the economic impact was negligible. But if the gilt market implodes, it will cause serious and widespread damage, hence the Bank of England stepping in as a market-maker of last resort by buying bonds. It is also notable that the financial market convulsion was so severe as to force UK prime minister Liz Truss to sack Kwasi Kwarteng, her Chancellor (finance minister), and roll back her tax cut package in an attempt to keep her own job. It neatly echoes the comment made three decades ago by James Carville, Bill Clinton’s election strategist, that he would like to be reincarnated as the bond market one day, since it can intimidate everybody, even presidents and prime ministers.

Finally, besides the outlook for inflation, interest rates and growth in the next few months, there are also longer-term questions.

Which trends are temporary and which ones are permanent? To what extent does deglobalisation occur as countries rush to secure key supply chains? How inflationary will this be, and can it stoke conflict? How does the war in Ukraine end and what does that imply for China’s stance towards Taiwan? One marker on this uncertain journey came in the past few days when the US announced wide-ranging restrictions on exports of computer chips to China, as well as the machinery used to manufacture those chips to prevent China from becoming a high-tech competitor.

It is no surprise then that bond and equity markets have sold off heavily in 2022. Perhaps the only reason headline equity indices aren’t completely down in the dumps yet is that some investors still cling on to the hope that the Fed and company will “pivot” soon and start cutting rates. This seems highly unlikely, and the optimism is set to be dashed, but it is also typical that when hope has evaporated the low point in market cycles is achieved.

Markets have also been very volatile. For instance, following the release of US CPI numbers last week, the US stock market initially fell 2%, then rallied to close above 2%, only the fifth time it has done so in the past three decades.

Uncharted waters

Traveling in these uncharted waters, do we have anything to guide us? The map is not the territory, as philosophers say (or used to say before Google Earth and similar services), since the map must abstract from reality. A map with every single detail would be too large to be useful, but even a simple map can help greatly across a vast terrain.

There are basic investment principles that still apply even in this polycrisis. We can’t predict the future – even the mighty IMF with its army of PhD economists will get its forecasts wrong much of the time – but we can take a few lessons from the past.

One is that markets tend to be very good at pricing in known bad news. It is the big surprises that cause big moves.

We don’t know if there are big surprises ahead, but markets surely already reflect the economic weakness almost everyone knows is coming. After all, global equities are down 25% in dollar terms year to date.

There are pockets of the global equity universe that already trade at recessionary levels, including South Africa and many other emerging markets, US mid and small caps, European industrials and so on. The mega-cap technology companies make the broader US market still look relatively expensive.

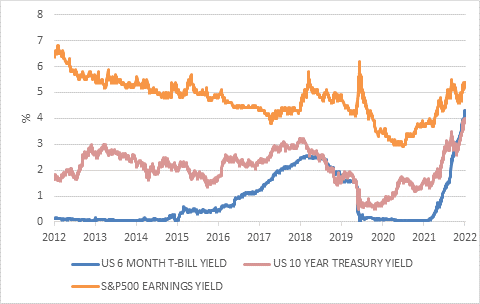

From TINA to TARA

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

Meanwhile, global bond and cash yields are also at levels last seen a decade or more ago.

For the first time since the 2008 crisis, equities are no longer the only place to be overseas.

We’ve moved from a There is No Alternative (TINA) world (i.e., no alternative to equities) to a There Are Reasonable Alternatives (TARA) world (with the alternatives to be found in the bond market).

In South Africa, bond yields have been extremely elevated since the market (not the ratings agencies) downgraded the government to junk status in 2015.

Bonds continue to offer attractive real yields given the improving fiscal situation and the Reserve Bank’s serious commitment to keeping inflation within its target.

History tells us that when markets sell off, future returns improve even as current returns fall. Put differently, market crashes make future investors richer while making current investors poorer.

Current investors should avoid making themselves even poorer by locking in losses and missing the upside. This is difficult when uncertainty and volatility are high and look set to remain high for some time, and often navigating their own emotional response is investors’ biggest challenge.

Izak Odendaal is an investment strategist at Old Mutual Wealth

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.