Southern California grocery workers authorize a strike amid contract negotiations

Battered by two years of pandemic stress, tens of thousands of Southern California grocery workers voted overwhelmingly to authorize a strike if supermarkets don’t meet their wage demands as negotiations on a new contract resume in the coming weeks.

The vote, taken over five days, could lead to walkouts beginning at some Albertsons, Vons, Pavilions and Ralphs markets stretching from Central California to the Mexican border.

The United Food and Commercial Workers announced that 95% of those voting at seven local unions approved a potential strike.

A three-year contract covering 47,000 workers at 540 stores expired March 6. Negotiations over a new agreement began in January but stalled three weeks ago. Workers seek substantial wage bumps, higher minimum hours for part-timers and store-level health and safety committees as pandemic concerns persist.

“These companies can either come to the table ready to negotiate a fair deal or we’re going to have to take this fight elsewhere,” said Kathy Finn, secretary-treasurer of UFCW Local 770 in Los Angeles and a lead negotiator.

Bargaining is set to resume Wednesday.

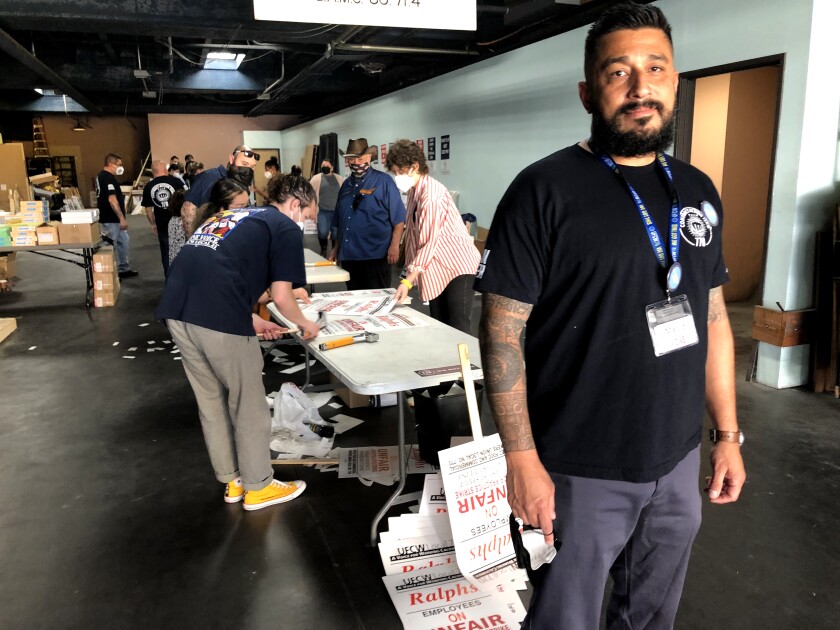

Rachel Fournier, a member of the UFCW Local 770 bargaining committee, stands at the union headquarters in Los Angeles as members made strike-ready signs Monday.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

The vote, which allows union leaders to call a strike if a pact can’t be reached, ratchets up pressure on two of the country’s largest grocery chains: Kroger, the parent company of Ralphs, and Albertsons, which owns Vons and Pavilions.

The showdown comes at a time of labor unrest across the nation. Grocery workers, conscious of their pandemic-related “essential” status, have dug in their heels, not just in California, but in Oregon, Colorado and other states.

Employees at other large companies including Amazon and Starbucks are seeking to unionize. And labor shortages are plaguing industries across the country as staffers switch jobs for higher pay. Inflation is surging to record levels in California and across the U.S.

Unlike Southern California’s nearly five-month grocery strike in 2003 and 2004 , during which the union’s full workforce walked out after the chains pushed to slash wages and benefits, this month’s authorization is framed as an “unfair labor practice” action. Under federal law, that allows walkouts at selected stores instead of a full-blown strike.

The union filed claims this month with the National Labor Relations Board that the supermarkets sought to intimidate and illegally influence workers — allegations the companies deny.

Grocery workers’ distress built over time as their pay has failed to keep up with the high cost of living in Southern California and companies have moved more than two-thirds of their workforce to part-time status.

In the Los Angeles area, a living wage — defined as the minimum income for a worker to meet basic needs — ranged from $19.22 for a single person without children to $34.01 for families with two working adults and three children in 2020, according to the latest data in a living wage calculator created by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The UFCW is asking that the highest paid longtime workers — food clerks who include cashiers and shelf stockers — get a $5 hourly raise by the end of a new three-year contract. They currently earn $22.50 an hour after five to seven years. The companies offered a $1.80 raise.

A third of the workforce falls into the food clerk category.

Another third of grocery workers — general merchandise clerks including deli food preparers and non-food stockers — now earn a maximum of $17.02 an hour. The union would raise that by $8 an hour over three years, saying they perform similar work to the higher-paid food clerks. The companies offered $2.

Bargaining has yet to begin on the lowest-paid third of the workforce — baggers and clerk’s helpers who earn slightly over the state’s $15 minimum wage.

Kroger and Albertson’s offer medical and retirement benefits unlike many non-union retailers. The UFCW’s wage proposals “would lead to $400 more in monthly grocery bills for most Southern California households [and] push customers to non-union competitors who do not respect collective bargaining,” said John Votava, Ralph’s corporate affairs director.

Non-union markets such as Amazon-owned Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s are fierce competitors. And non-union retailers such as Walmart and Target have expanded their grocery businesses in recent years.

Supermarkets traditionally operate on thin profit margins of about 2%. But the pandemic turbocharged revenues as restaurants closed and more people ate at home. Kroger’s operating profit nearly doubled to $4.3 billion from 2019 to 2021.

In 2020, the company paid out $1.3 billion to investors — money that workers say should have gone to pay them more as they faced COVID-19 risks on the job. Kroger Chief Executive Rodney McMullen was criticized for collecting a $22.4-million pay package in 2020 — his largest ever — even as the company ended a $2 an hour hazard bonus for frontline workers after two months.

A strike would affect tens of thousands of workers across 540 grocery stores stretching from Central California to the border with Mexico.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

When the cities of Los Angeles and Long Beach passed ordinances last year requiring chains to offer several months of hazard pay, Ralphs closed five markets saying they were “financially unsustainable.”

“Grocery workers are essential,” said John Grant, president of Local 770. “They’re not easily replaceable given the labor shortage. We don’t want another disruption. but we’re prepared to strike.”

At the Los Angeles headquarters of UFCW Local 770 this week, two dozen grocery workers hammered wooden sticks onto signs reading “STRIKE,” “HUELGA” and “PLEASE RESPECT OUR PICKET LINE” in red, black and white letters.

Among them was Rachel Fournier, a 44-year-old cashier, who has worked 17 years at a Los Angeles Ralphs. Her hourly pay is now $22.50, the company’s maximum. Despite repeated requests, she has never been able to gain full-time status.

“Working 28 hours a week doesn’t pay the rent,” she said. “It’s not going to put food in your kids’ bellies.”

Full-time workers get slightly better benefits and more holidays, she said, so the company’s computer system flags workers whose hours rise “and they bump you down to prevent you from qualifying.”

Fournier’s husband is disabled after a car accident, and she has taken in her sister and a roommate as boarders to make ends meet. Still, she said, she regularly runs out of money before her paycheck hits her bank account.

“Twenty years ago this was a middle class job,” she said. “But the companies have been squeezing and squeezing us with meager wage increases over the past few contracts.”

Over two years, 7,709 grocery workers in Local 770 have contracted COVID-19, according to data provided to the union by the stores. The pandemic has created “a spirit that we need to stand up for ourselves,” Fournier said. “People are fed up and they’re eager to walk out.”

Marco Escalante, 46, who works the night shift as a stocker at the Vons in Echo Park, wants to move to full-time work but said he usually gets 30 hours a week.

(Margot Roosevelt/Los Angeles Times)

Marco Escalante, 46, was also at the headquarters, stacking signs in preparation for a strike.

After 24 years at a Vons in Echo Park, Escalante makes $22.50 an hour on a midnight to 8:30 a.m. shift unpacking pallets and stacking shelves. He would like to work full time but normally gets just 30 hours a week.

Given inflation, the company’s offer of 60 cents an hour more for each of the next three years amounts to a pay cut and “a slap in the face,” he said.

Escalante, who has a working wife and three children, was a leader in the 2003-04 strike. “After almost five months, they broke us,” he recalled. “Every contract since then has been 20 cents here, 20 cents there. I was making more money 15 years ago than I am now.”

The pandemic has changed the bargaining dynamic, he said. “Our members got sick and took it home. Customers were throwing fits at the stores. And the companies were saying you only have so many sick days so you have to come to work. They’ve shown no empathy for our sacrifices.”

Escalante sees ever-stronger pro-union sentiments among younger workers. Authorizing a strike, he said, shows the companies, “We know they’ve made billions in profits and we’re not afraid to go out. There’s a big change coming.”

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.