Should I worry about a recession? What Californians should know

By many metrics, the U.S. economy is chugging along at a healthy clip. The latest readings on some key economic indicators are all good — unemployment is low, quarterly profits are high, home construction is up, retail sales continue to grow, and the gross domestic product showed solid growth.

The same is true for California, whose GDP growth and job gains outpaced the country as a whole for much of the last year. Los Angeles did particularly well on the jobs front, according to Beacon Economics, and its economy, hamstrung by pandemic-related restrictions, “is expected to transition from recovery to expansion in the early months of 2023.”

And yet, a recent survey found that 4 in 5 Americans expect a recession this year.

“People are trying to talk themselves into a recession right now,” said David Shulman, an economist who advises UCLA’s Anderson Forecast.

Even Shulman sees trouble coming, however — just not until 2024. That’s because of the eye-popping acceleration in inflation, which could eventually trigger a downturn. Southern Californians are exposed to some of the worst of its effects, given their gasoline-sucking commutes and high housing costs.

To help you understand the risks and what you can do to prepare for them, here are some facts and pointers about recessions and the current economic situation.

What is a recession?

The National Bureau of Economic Research — a private nonprofit, not a government agency — is the group that economists regard as the official scorekeeper of recessions. It defines a recession as a “significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months.” Typically, that’s meant at least two consecutive three-month periods when GDP has declined, taking inflation into account.

That’s the technical definition. What recessions mean in human terms is a surge in unemployment as demand for goods and services drops, causing businesses to lay off workers, which further suppresses demand for goods and services. With companies retrenching instead of expanding, the unemployed have a tough time finding work, which exacerbates the slowdown.

It’s a vicious cycle that the government tries to interrupt by pumping cash into the economy — normally by paying unemployed workers a portion of their previous wages for several months, but also occasionally by sending stimulus checks or enacting tax holidays. In the most recent recession, the federal government and California’s state government opted for stimulus checks.

There is also a psychological dimension, when consumers lose confidence in the economy and rein in their spending. That’s happening now, according to the Conference Board’s survey of consumer confidence, which found the public growing more pessimistic about the future despite feeling better about their current situation.

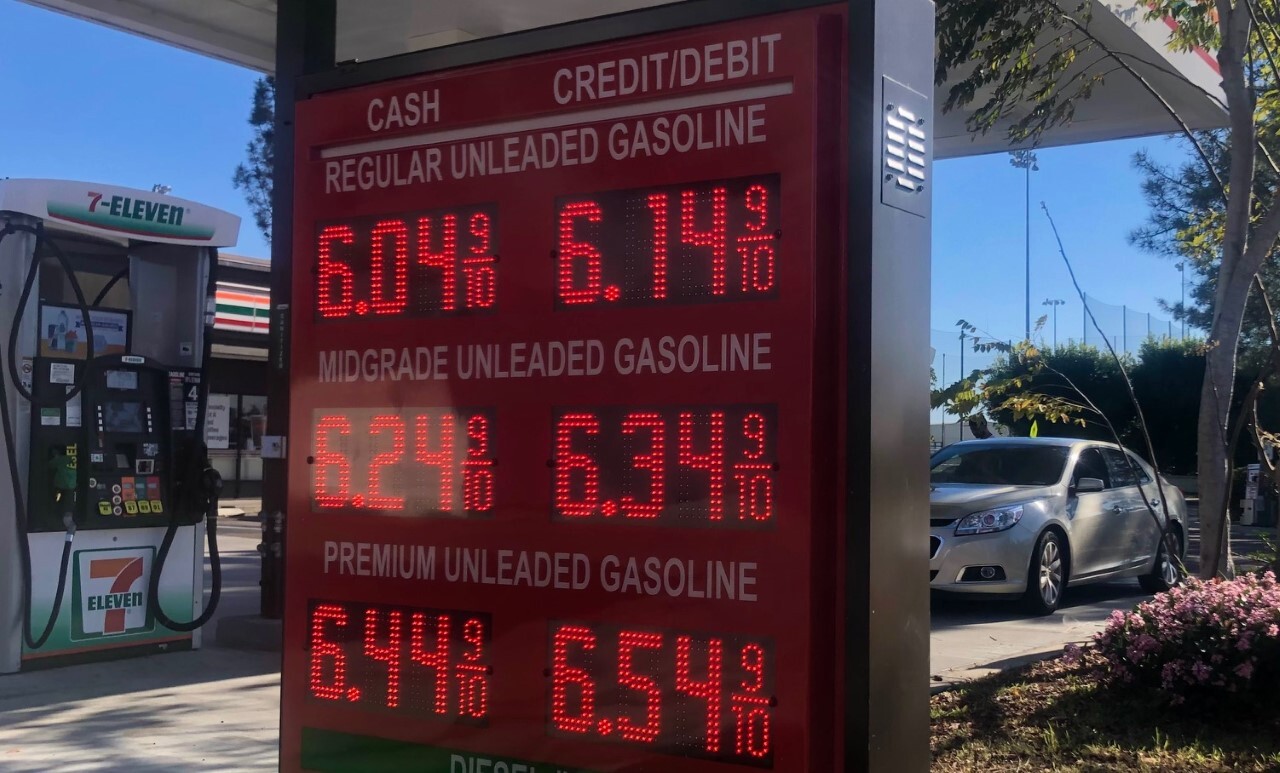

“When you see $6 for gasoline,” Shulman said, “you feel poor. In some people’s minds, that’s a recession.”

What causes a recession?

Economists point to a variety of factors that can send the economy into reverse. The U.S. has endured three recessions so far in the 21st century, and each had a different cause.

The downturn from March to November 2001 was tied to steep losses in the stock market, first when the dot-com bubble burst in late 2000, then when terrorists flew planes into the World Trade Center on 9/11. The Great Recession, which ran from December 2007 to June 2009, was caused by a financial-industry meltdown tied to the subprime mortgage fiasco. And the brief but extreme downturn from February to April 2020 was a consequence of COVID-19 and the government-ordered restrictions on travel and commerce.

The common thread in each of those was a sharp decline in demand — either businesses and individuals had less money available or they weren’t able to spend what they had.

The situation is dramatically different today. Demand is extremely strong because there’s plenty of money sloshing around the economy, a situation created by rock-bottom interest rates, high employment, rising wages and aggressive federal borrowing and spending (to cover stimulus checks, among many other things).

But file this one in the too-much-of-a-good-thing category because the demand has greatly exceeded the supply of goods and services.

“Everywhere you look you see nothing but an insane degree of consumption,” said economist Christopher Thornberg, founding partner of Beacon Economics in Los Angeles. Defenders of the big federal aid packages say that millions of Americans affected by COVID needed a rescue. But Thornberg counters, “No matter how you slice it, the federal government overstimulated this economy at an insane level over this last year.”

Rapidly rising stock and home prices helped increase U.S. household net worth by more than a third since the start of the pandemic. “Americans are flush. We feel rich. And therein lies the problem,” Thornberg said. “We’re not rich. The economy does not have the capacity to produce products at the level people want them. In other words, this is false wealth.”

This mismatch — which some economists blame entirely on the Federal Reserve pumping money into the system and others attribute at least in part to the COVID-related problems in supply chains, at factories and in service industries, exacerbated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine — is driving prices up. And prices will continue to go up, Thornberg said, until demand and production capacity are back in synch.

In response, the Federal Reserve is starting to raise interest rates, making it more expensive to borrow money. That change will affect businesses as well as consumers. Jim Doti, an economics professor at the Center for Economic Research at Chapman University, said the Fed is also dropping hints that it will start selling some of the bonds in its portfolio; doing so would increase upward pressure on interest rates and reduce the supply of money.

The one-two punch of higher prices and higher interest rates applies the brakes to a growing economy. The Fed’s goal is a “soft landing” in which the tighter money supply eases demand while still allowing for some economic growth. But there are plenty of economists who fear that the Fed waited too long and acted too meekly, allowing inflation to become powerful enough to trigger a downturn.

“There is no soft landing,” Thornberg said. “The horse is out of the barn.”

Is Southern California more or less at risk?

Noting the long commutes that typify the state, Shulman said, “California’s obviously more sensitive to what’s going on now because of gas prices.” For people who have no alternative to driving — such as the commuters forced by high housing costs to live far away from their L.A. workplaces — the roughly 50% increase in price per gallon over the last year has been the equivalent of a pay cut.

The higher fuel prices could also hit California harder than other parts of the country, Doti said, because of the state’s reliance on tourism. “The first thing that consumers cut is discretionary spending,” which includes travel, he said. “That’s why the COVID recession hit California harder.”

The state’s extremely high housing prices are another problem, Doti said. Property values should drop later this year, and more deeply in California than they will elsewhere in the U.S., he said. But he added that rising interest rates will probably make homes less affordable even at lower prices.

The double whammy of higher mortgage interest and extraordinarily high house prices will probably deter not just entry-level home buyers, but also people looking to move up from their first home, Shulman said. And for renters, he said, the likely increase in costs is even worse than the federal inflation numbers suggest. That’s because many tenants are on yearly leases, which delays the day of reckoning on price hikes.

Then there’s the relatively high percentage of Californians still looking for jobs. The state’s unemployment rate was 4.9% in March, more than a third higher than the national average of 3.6%. If you start with a higher rate going into a recession, Shulman said, “you’re going to end up with a higher rate.”

The stock market, which has lost its mojo in 2022, is another risk factor for California, Doti said. The state’s tech-heavy economy is rich in start-up companies that rely on borrowed funds. If the market turns bearish, “those companies that have borrowed more will have a much more difficult time rolling over that debt,” he said.

And if a recession does hit, Shulman said, it would pose one other unusual problem for California: “It will increase the pressure for outmigration, which would be a negative for the economy…. If you see less opportunity in California, all of a sudden the rest of the country may look more attractive.”

Yet California has some factors operating in its favor.

Shulman said Southern California still has a presence in the defense industry, albeit a diminished one, and it stands to benefit from the federal government’s increasing outlays for military hardware during the Ukraine war.

He also said that despite the increase in fuel costs, the state’s hospitality and tourism industries should benefit from the “huge pent-up demand for travel” now that few COVID-related restrictions remain in effect. Similarly, Shulman said, there’s a large unmet need for home and auto purchases that should sustain demand here.

On top of that, he said, “there’s huge capital spending coming around,” related at least in part to clean energy. “This, to me, doesn’t make a recession,” Shulman said.

What can you do to defend yourself?

Certified financial planner Barbara Ginty, host of Future Rich podcast, said the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of a personal emergency fund. She has heard clients call themselves “emergency-proof,” but “2020 proved that you, yourself, might not have an emergency, but you cannot prevent an emergency of a global event.”

“Having that good emergency fund can alleviate a lot of that financial stress” she said.

Nevertheless, millions of Americans don’t have a stash to draw on if things go south. According to a Bankrate survey last year, a little more than half of the people sampled didn’t have enough saved to cover three months of expenses, and a quarter of the people sampled had no emergency fund at all.

So although the economy is still humming along, it’s a good idea to try to set aside some money. And the place to start, financial advisors say, is by creating a budget.

“Budgets are your financial strategy,” said author Jesse Mecham, founder of the personal finance site youneedabudget.com. “And a strategy can involve cutting back. But it doesn’t have to mean that specifically or necessarily…. A budget is just a plan, it’s not a task master, it’s not a warden and you’re now in prison.”

Creating a budget is mainly an exercise in figuring out where your money is coming from and going to, and seeing which things can be adjusted and which ones can’t. The main point, Mecham and Ginty said, is understanding where your money is going and what’s most important to you.

“You just have all these different options if you’re very aware of what your money is doing and what you need it to do,” Mecham said. “Most Americans just really aren’t aware of what their money is doing. They’re very reactive.”

Thanks in part to the stimulus checks, Americans saved far more during the early days of the pandemic than they had in the previous four decades, although the savings rate has since come back down to Earth. How much you’ll need in your emergency fund depends on your personal situation and your dependents, Ginty said, but having enough to cover one month of expenses is a good starting point.

Mecham said a financial cushion can give people time to find the silver lining in a downturn. “For a lot of people it’s an opportunity,” he said. “You can be more picky about the job you accept, more picky about the clients you choose to work for, more strategic about how to share child duties.”

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.