She went to Colombia to exhume her grandfather — and returned with a blazing memoir

On the Shelf

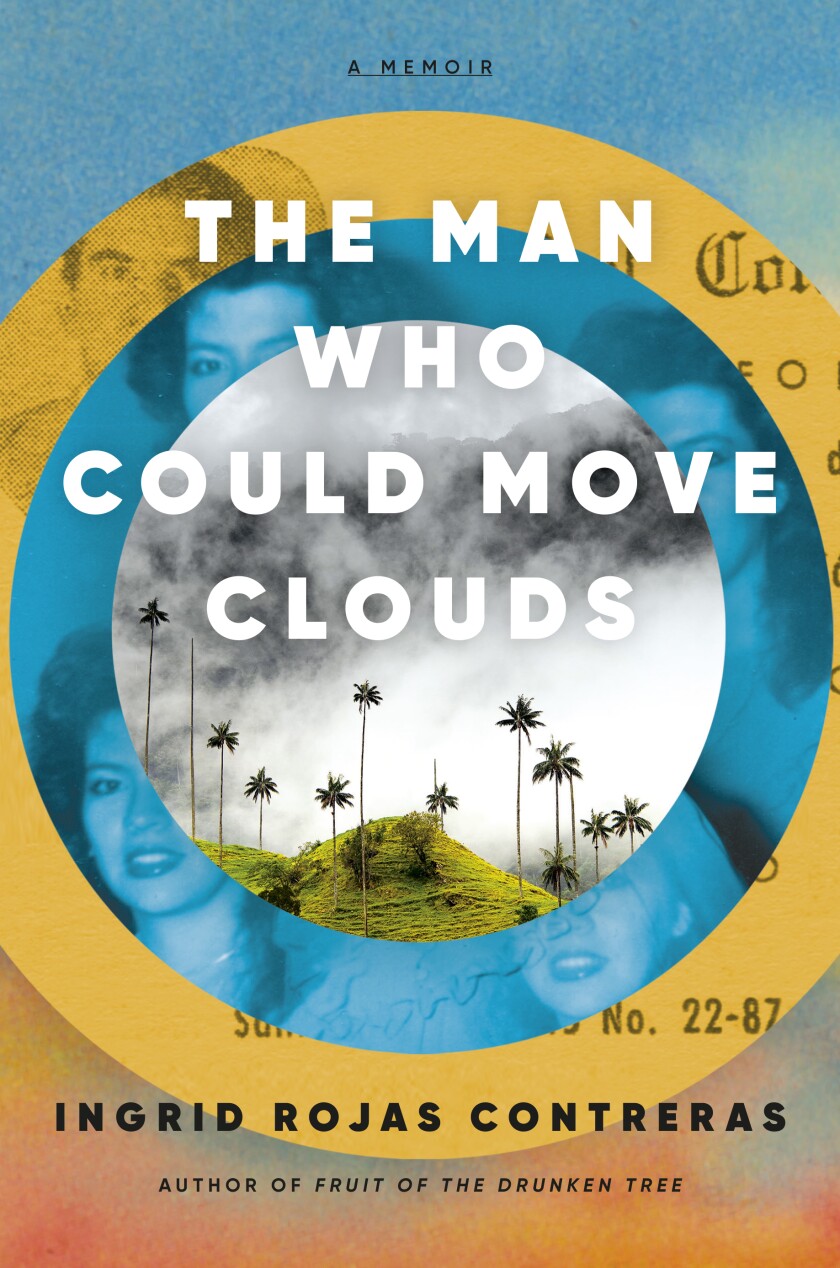

The Man Who Could Move Clouds

By Ingrid Rojas Contreras

Doubleday: 320 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

It’s no knock on Ingrid Rojas Contreras’ new memoir, “The Man Who Could Move Clouds,” to say that it sometimes reads like magical realism. The Colombian American writer’s journey to unearth her family’s legacy explores supernatural gifts (her mother a fortune-teller, her grandfather a curandero, or shaman), cycles of amnesia and a fateful disinterment, all against the backdrop of her native country’s past colonialism and modern-day violence.

As a teenage emigrant to the U.S., Rojas Contreras had shelved her family stories; they belonged to a past she had left behind after her parents left Colombia over guerrilla warfare and drug violence. It was only in the aftermath of a bike crash resulting in eight weeks of amnesia — an uncanny echo of her mother’s childhood accident — that the past reached into the author’s present, propelling her into a lyrically rich excavation of memory, mythology and history. “There are many types of hunted treasures,” the author writes, “secrets long buried, come to light. Knowledge long lost, then returned.”

Rojas Contreras’ writing becomes fable-like at times. Her grandparents’ tales alone feature a dry well as a site of treason, a domesticated anaconda becoming part of the furniture, a mysterious creature bathing in a lagoon and the improbable journey of a decorative skull. In other moments, as she strives to piece together her identity, the author’s sentences rings like incantations, as if she were casting a spell on herself and, by extension, the reader.

In this nonlinear memoir, Rojas Contreras’ deceptively free-flowing prose is in fact carefully structured. Each object in the narrative works as both image and metaphor and sometimes serves to illustrate an intellectual argument, taking on double and tripling meanings. Rojas Contreras, also the author of the novel “Fruit of the Drunken Tree,” spoke to The Times via Zoom from her Bay Area home about the gifts of amnesia and the necessity of writing for “the front row.” The conversation is edited for clarity and length.

You write that before coming to the U.S., you thought everyone “pored over dreams, received prophecies,” as your mother did. At what point did you stop seeing these stories or skills as commonplace and as something you wanted to explore in writing?

When I told Colombians and other South Americans that my grandfather was a curandero, I often received a story back: “Oh, my grandma used to say this,” or “In my family we do this.” Growing up, I assumed that this was how the world was. When I arrived in the U.S., I was 17 or so, and suddenly all these things were unheard of and there was no language for what my life had been before. As a new immigrant, I didn’t want to go through the effort of explaining myself. Then, I lost my memory, and post-amnesia it all came back with such a sense of wonder. At that point, I could not stay away from the page, I could not stop telling people the story.

Was there one central question or argument you kept coming back to in this sweeping account of family, fables and colonialism?

My aunt, my mom and I all dreamt of my grandfather wanting to be disinterred, and we decided in real life, “OK, there are three dreams, so we have to do it.” I knew this is where I wanted to start — travelling back to Colombia and going through the motions of the disinterment. When I was back in this apartment I hadn’t been in since I was a child and was assaulted by memory of life in Colombia, I understood that we were doing a physical unearthing of my grandfather and also an emotional unearthing of whatever it was that I tried to repress or had forgotten. That’s something that happens to immigrants: “Oh, I’m going to leave everything behind and I’m going to be a new version of myself.” Being back and doing this supernatural errand as a family, I was interested in the parts of myself that I had discarded.

You write about European settlers having reined in Indigenous traditions and the impact they had on natives’ sense of self. When did you realize this family memoir was also a political story?

There are many kinds of interruptions, and one of them comes from the way we were colonized in Colombia and the other one is this modern violence in the ‘90s and how a lot of people had to leave. To me, that felt political, and I felt I had to bring everything into the narrative.

I find your exploration of both personal and cultural amnesia fascinating: Amnesia as knowledge, as inheritance, as freedom, as survival, as deliverance, as abundance…

Culturally, we tend to think amnesia is bad, but I fell in love with how meditative it felt, living moment to moment. Because things did not have names, internally or emotionally it felt like they were exact and the moment I would put language to something it would become inexact. When things become fixed with the words we have for them — because language is inexact — our perception also becomes inexact. When I didn’t have words attached to things it felt like I knew what the world was. It was a complicated, beautiful experience.

You encourage writers of color to free themselves from the expectation of having to be “tour guides” in their stories for a white audience. Where is the fine line between telling stories in all their complexity, which can feel inaccessible to readers unfamiliar with certain cultures, and simplifying them to educate readers?

When I read stories in the U.S., not everything was explained because it was assumed that the audience was people who grew up in the U.S. I grew up reading things that weren’t for me and either had to put the book down and look things up or try to absorb the world the book was trying to build. Many writers of color have this experience and are comfortable with that. White readers are not used to not being the centered audience. It’s a disservice if your writing is geared toward a white audience and you’re excluding those you are trying to talk to. In a book, there are many opportunities to try to bring that outside audience in and explain a few things.

I think of it as an auditorium: In my first row are the people I am talking to and, in the back, people who are not familiar with Colombian culture. When I start to explain something, I try to be conscientious of whether this front audience will get bored. I try to keep that balance. As readers, we should all strain to be in the zone where we come to the work, as opposed to demanding that the work always comes to us.

Nasseri is a writer, journalist and former Middle East correspondent for Bloomberg.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.