Review: The tragedy and farce of Rudy Giuliani, explained

On the Shelf

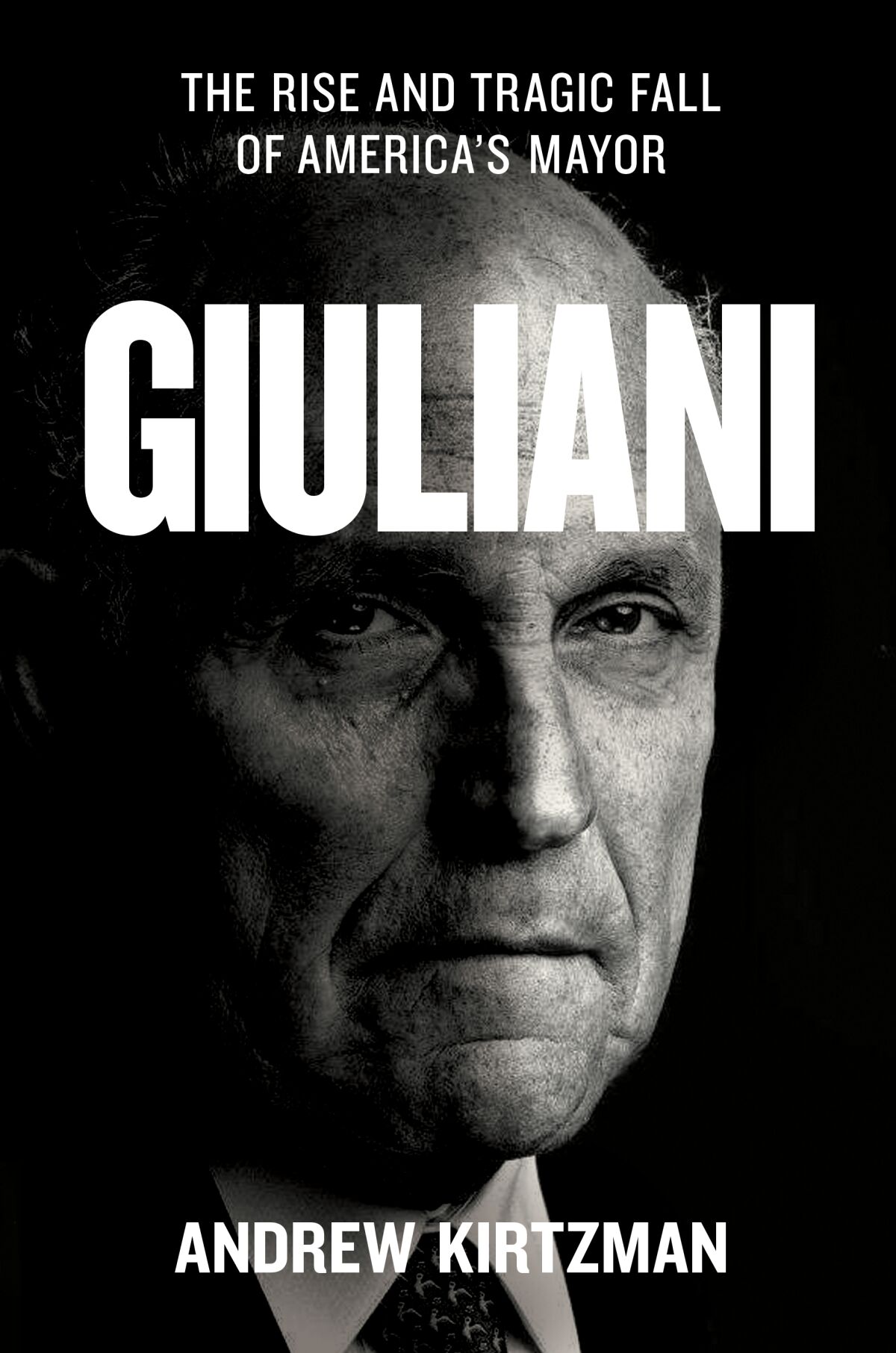

Giuliani: The Rise and Tragic Fall of America’s Mayor

By Andrew Kirtzman

Simon & Schuster: 480 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

After Rudolph W. Giuliani married his third wife in 2003, he used to leave her notes when he left for work in the mornings. He would write “I love you” at the end, then draw a heart around the words.

He also kept a baseball bat under the bed, just in case. He might have been at the pinnacle of his fame, splitting his time between estates in the Hamptons, Palm Beach and Manhattan, but he was still the son of a bone-breaking enforcer for loan sharks in Brooklyn.

It’s this mix of vulnerability, neediness, paranoia and hostility that lingers from “Giuliani: The Rise and Tragic Fall of America’s Mayor,” a new biography by Andrew Kirtzman. Out this week, the book cuts through the myth and caricature that has too often defined Giuliani, the former New York City mayor who has more recently served as a wingman for President Trump’s assault on democracy.

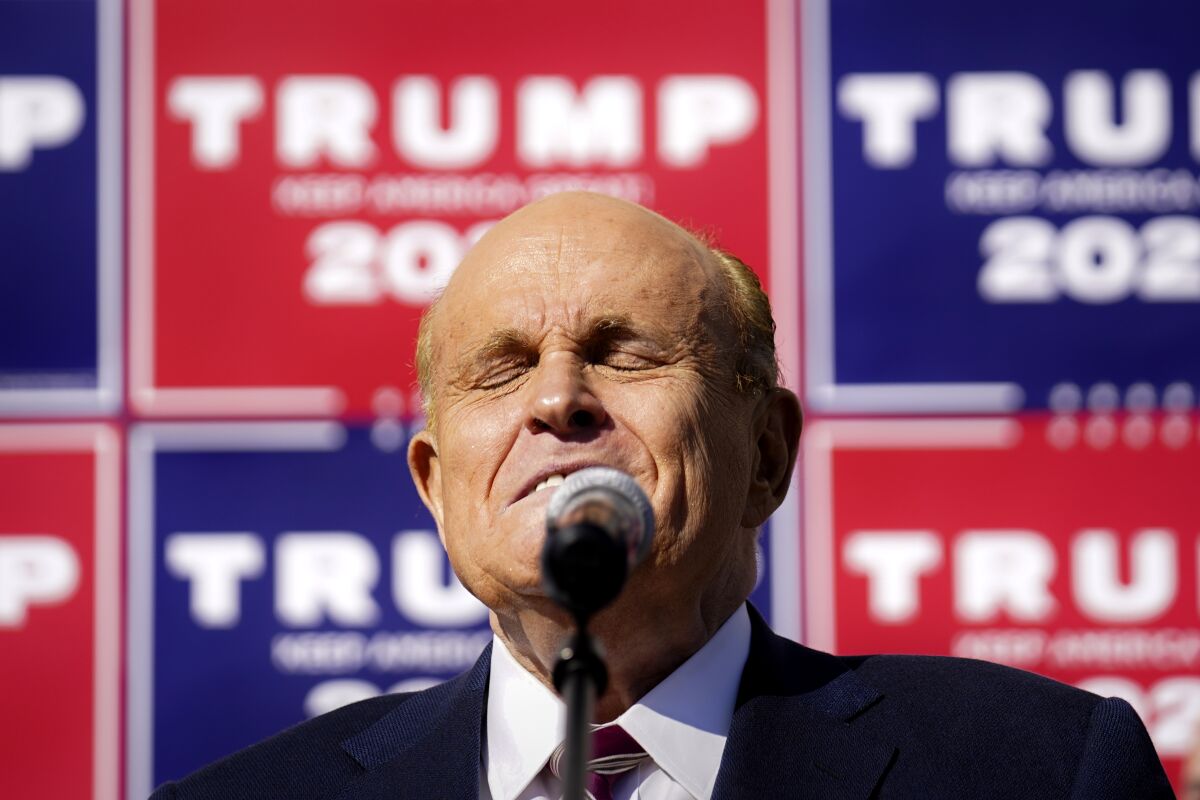

Rudy Giuliani at Four Seasons Total Landscaping on Nov. 7, 2020 during what many see as his darkest hour. In a new biography, Andrew Kirtzman connects the dots across the former mayor’s highs and lows.

(John Minchillo / Associated Press)

As a former television reporter for NY1, Kirtzman knows the man better than the pundits who have often scratched their heads about the Giuliani they thought they knew. In his first book about him — “Emperor of the City,” originally released in 2000 — Kirtzman wrote, “I thought of him variously as a great man and as a mean-spirited one, a visionary and an opportunist, a transforming leader and an intolerant one.”

His assessment is only grimmer now. If Giuliani’s story is a tragedy, Kirtzman argues that it’s self-inflicted through a combination of alcohol, sanctimony and a bottomless need for attention.

Although he is one of the country’s most recognizable political figures, the ex-mayor’s life is often summed up in two snapshots. The first is Giuliani caked with ash from the destruction of the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, shepherding his traumatized city through its darkest moment. The second is in a sweltering room at Republican National Committee headquarters, hair dye streaming down the sides of his face as he spins conspiracy theories about the election being stolen from Trump.

The greatest service of Kirtzman’s book is connecting the dots between these points, almost two decades apart.

“When he left the mayoralty, he lost his grip on the zealous mission that had driven him his entire career, which was to wield power and impose his view of right and wrong on others,” Kirtzman writes.

As Giuliani stayed busy by making money, consulting for corporations like OxyContin manufacturer Purdue Pharma, his third marriage, to Judith Nathan, was no refuge. She feuded with Giuliani’s staff, most memorably over a selection of hats that were picked out for her to wear to Buckingham Palace when Giuliani received an honorary knighthood in 2002.

Nathan also played on Giuliani’s insecurities when they argued. “Rudy would tell me, ‘Who do you think you are?’” Nathan recalled. She would reply, “Who the f— are you, your father was in Sing Sing,” a reference to the notorious New York prison where the elder Giuliani did time after being arrested for his role in an armed robbery.

Giuliani ran for president in 2008, entering the Republican primary leading in the polls, but it was a disaster. Kirtzman writes that “emerging with just a single delegate was a catastrophic ending to a lifelong ambition.” Nathan said she “couldn’t get him out of bed,” and they relocated to Palm Beach. He spent his days moping around his in-laws’ condo and smoking cigars on the terrace while wearing a bathrobe.

Andrew Kirtzman, author of “Giuliani: The Rise and Tragic Fall of America’s Major,” has reported on his subject for decades.

(Kyle Froman)

It was then, at one of Giuliani’s lowest moments, that his relationship with Trump deepened. After photographers found Giuliani at the condo, he moved to Mar-a-Lago. Kirtzman writes that he stayed with Nathan at a bungalow across the street and used a network of tunnels under the property to remain out of sight.

“Donald kept our secret,” Nathan said.

Giuliani and Trump had known each other for years, and Giuliani had been a sort of proto-Trump as mayor, with “an instinctive ability to press the outrage button at whim.”

The law-and-order mayor in fact lived and governed in a constant state of chaos. In 1999 and 2000, Giuliani stoked racial tensions after plainclothes cops killed a West African immigrant, battled prostate cancer, announced he was divorcing his second wife and then decided he wouldn’t run for the U.S. Senate against Hillary Clinton.

Rudy Giuliani, left, with Donald Trump during a skit played at a roast of the then-mayor in 2000.

(Kyle Froman)

Although his tenure as mayor had been deeply controversial, his international stature exploded after the Sept. 11 attacks. Kirtzman spent that morning with the mayor as they fled for their lives in Lower Manhattan. He doesn’t shortchange his subject’s bursts of inspiration. At a moment of terror, Giuliani found words to console and galvanize the city and the country. But Kirtzman argues that Giuliani also used his story of heroism as a shield against accountability. His administration had failed to prepare for potential attacks, and communication problems hampered the response.

“His performance on September 11 was a tapestry of inspired leadership and fatal mistakes,” Kirtzman writes. “The public saw only part of the picture that terrible day; the rest was shrouded in adulation for years.”

Giuliani’s service to Trump has eroded that. He helped defend the former president during the Russia investigation, then burned through his credibility in a foolhardy search to tarnish Joe Biden in Ukraine. The result was Trump’s first impeachment.

After Trump lost the election, Giuliani fueled his grievances and lies about voter fraud. Four days after the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, Giuliani’s girlfriend wrote a letter to Trump asking for three things for him— payment for legal services, the Medal of Freedom and a “general pardon.” (It’s unclear if Giuliani was aware of the letter, which Kirtzman says he reviewed, and it may never have reached Trump himself.)

“In a lifetime of crusades, this was his grand finale, and it ended in a crescendo,” Kirtzman writes.

Of course, Giuliani’s final act remains unknown. The New York Times recently reported that he is unlikely to face charges of illegally lobbying on behalf of Ukrainian officials. However, prosecutors in Georgia have described him as a target in a separate criminal investigation over efforts to overturn the last election.

Perhaps Giuliani has even farther to fall.

Megerian is the White House reporter for the Associated Press and a former staff writer for The Times

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.