When the top brass of supermarket chain Wm Morrison gathered for their away-day in November, the company’s response to the pandemic was not the only topic on the agenda. Its share price remained stubbornly low, and board members and senior managers discussed the odds that a lowball takeover offer would prove triumphant.

“We could see we might be vulnerable,” says one person who attended the meeting, held at the Bradford headquarters of a company that traces its roots to a 19th-century Yorkshire market stall.

Seven months later, Morrisons disclosed two takeover bids in quick succession from rival US private equity firms: an £8.7bn bid from Clayton, Dubilier & Rice in June that it rejected, and a £9.5bn offer from SoftBank-owned Fortress Group that it backed last weekend. Shareholders now expect a bidding war for the retailer, and Apollo Global Management, the private equity behemoth, has indicated it may enter the fray.

Morrisons is the latest example of a dramatic shift in corporate Britain — one that has accelerated during the coronavirus pandemic. For much of the past century, the economy has been dominated by companies listed on public markets — their shares available to investors to buy and their managers facing a certain level of accountability. But now a growing portion of the economy is being shifted into private hands.

The private equity industry, a clear winner from both the economic upheavals since the financial crisis and the market dislocations created by Covid-19, is striking larger and more frequent deals.

“Private equity is rampant . . . they are the dominant force now,” says Sir Martin Sorrell, founder and chair of the listed advertising group S4 Capital. “We seem to be moving away from the pandemic and everyone is feeling more ballsy. As long as interest rates remain low there is no reason for this to change.”

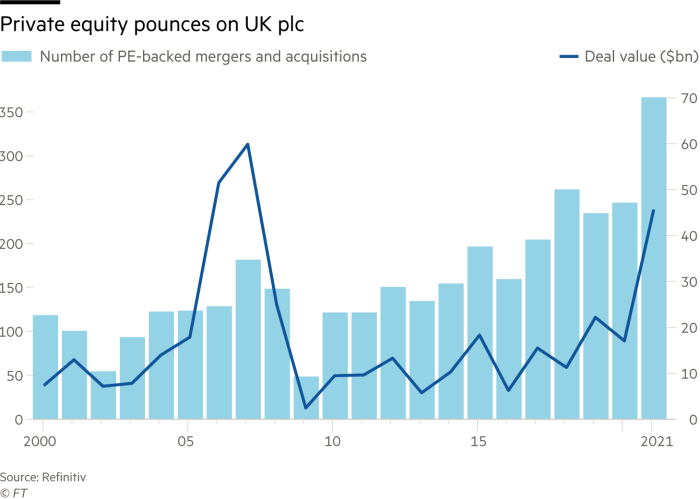

Private equity firms have struck more deals in the UK in the first half of the year than in the same period in any year on record. The number of UK buyouts is up almost 60 per cent in 2021 compared with the same period in 2019, according to figures from Refinitiv — while across the EU it is up just 14 per cent. Private equity firms have announced approaches to 13 listed UK companies since the start of 2021, having made no more than five in the same period of any year for the past decade.

The companies that have been bought in recent deals include household names such as supermarket chain Asda and breakdown service the AA. The leading buyout groups are staffing up their UK operations; US-based KKR, Blackstone and Carlyle have appointed additional dealmakers to focus on British companies.

The structural shift towards private equity is being driven partly by the low interest environment — a double benefit to the sector. First, it has led institutional investors, eager for higher yields, to plough money into buyout firms which promise generous returns. And second, it has made the borrowing that is central to the private equity model cheaper than ever.

The buyout industry is now sitting on a record $1.7tn of firepower, and it is under pressure to spend it.

Sir John Kay, one of the UK’s leading economists, says “market distortions set up by quantitative easing” have contributed to a long-term shift from public equity to private equity, which uses leverage to try to generate higher returns.

That money is increasingly being directed to the UK. Lionel Assant, European head of private equity at Blackstone, which this year bought Butlin’s owner Bourne Leisure, says the UK’s “pro-business environment” and “confidence driven by the rapid UK vaccine rollout” are among its attractions.

Others point to the UK’s liberal attitude towards takeovers, which makes it an easy place to buy and restructure companies — unlike a country such as France, where strict labour laws make mass lay-offs difficult and governments sometimes take a firm stance against foreign acquirers. Private equity firms have been able to lure senior executives with the prospect of higher pay and less public scrutiny.

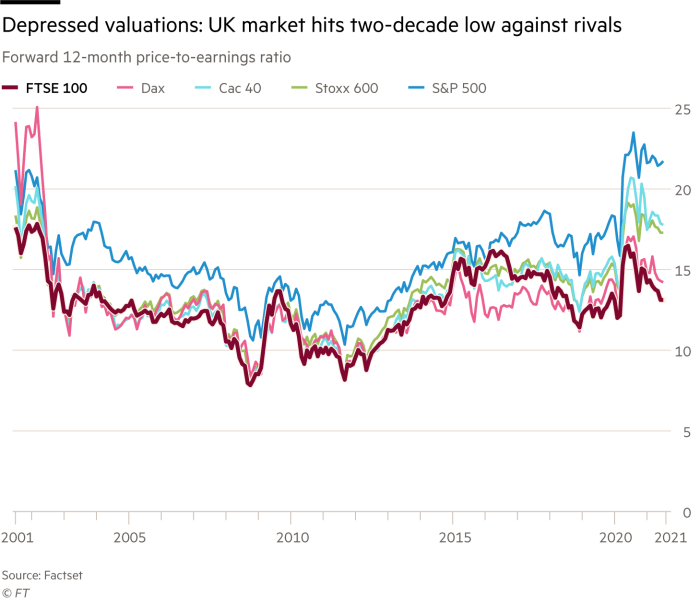

The boom in private equity deals in the UK is also being driven by the relative cheapness of equities compared with other markets. Since the Brexit vote in 2016, investors have pulled more than £29bn from UK equity income funds, according to figures from Morningstar.

That has left the UK stock market looking cheap compared with the US and Europe. On a price to earnings basis, the gap between the UK market and other leading economies is at its widest in the past two decades, according to JPMorgan.

“If you’re sitting in the States right now where the market is pretty bonkers, the UK [stock market] looks quite attractive,” says a senior dealmaker at another US private equity firm. “Brexit is behind us and the economy is looking pretty good on the basis of the Covid recovery.”

But private equity’s advance is causing alarm. Some politicians and industry executives fear that the increase in debt levels that accompanies such deals could lead to high-profile corporate failures. Others question whether it makes sense for it to be so easy to acquire a listed company.

“Britain is open for business in the same way that a car boot sale is open for business,” says Lord Paul Myners, the former City minister. “Basically any predominantly British-listed company, with one or two exceptions . . . is vulnerable to a takeover offer in a way that doesn’t apply elsewhere in the world.”

Short-term thinking

There has been a longstanding debate about whether Britain’s system of shareholder capitalism is too short-termist in its approach — a discussion that the flurry of private equity takeovers has renewed.

Myners says the vulnerability of listed companies is a result of shortcomings in the “rules of the game” of the UK investment management industry: an excessive emphasis by equity fund managers on short-term performance.

“This means it’s quite difficult to give up the share price pop that comes with a bid because it could be the difference between a good quarter and a bad quarter,” says Myners, who was chair of Marks and Spencer at the time of Philip Green’s failed bid for the UK retailer.

He criticises what he sees as “pretty supine boards of public companies, who rarely have the stomach to take on private equity firms”.

James Macpherson, former deputy chief investment officer of fundamental equities at BlackRock, says private equity’s offers can be hard for shareholders to resist. “‘When a big premium is offered for a company whose shares have gone nowhere for a few years, it’s very tempting to take that rather than give the current management the benefit of the doubt,” he says.

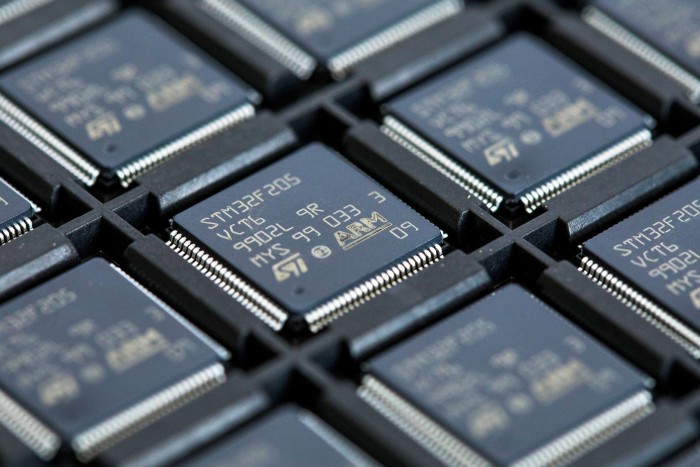

“Equally even for a great company, we’re all kicking ourselves for selling Arm at the price we did five years ago,” he adds, pointing to the case of the Cambridge-based smartphone chip designer which was acquired in 2016 for £24bn by SoftBank, despite the opposition of its largest shareholder, Baillie Gifford. The Edinburgh-based fund manager felt the deal would deprive Britain of a national tech champion, and Arm’s technology has become central to developments in the processing power of electronic devices.

“The Arm management were acquiescent [in the takeover] too,” says Macpherson, and Baillie Gifford was unable to muster up enough support to help Arm remain independent.

Danuta Gray, chair of St Modwen, the FTSE 250 property group that Blackstone has agreed to buy, says the approach from the private equity giant was a “frustrating” reminder of the gap in valuations between the public and private markets.

The board rejected Blackstone’s first five attempts to buy the business. Eventually they agreed a £1.24bn bid, which was raised to £1.27bn after shareholders objected to the price.

While the offer came with the promise of an accelerated investment programme, she says, if the company had a higher valuation in the public market “we could have talked to shareholders about our own equity raising to fund expansion plans”.

“UK equities are being undervalued compared to overseas peers,” she says. “It’s a shame to see a company like St Modwen taken from the stock market, but I am confident that the business still has a great future.”

The number of listed companies in the UK has fallen by about 40 per cent compared with 2008, according to a review of listings by Lord Jonathan Hill, the former EU financial services commissioner.

That has led large investors in listed securities such as Baillie Gifford to increase exposure to unlisted companies, notably in the US and China, in pursuit of returns. And venture investors are christening “unicorns” — private companies valued at $1bn — at a record pace.

“There’s been a shift in the allocation of investors such as pension funds and sovereign wealth funds from public strategies to private capital,” says Borja Azpilicueta, global head of HSBC’s financial sponsors group.

Life under private equity ownership

For the private equity firms and their advisers, the industry represents one solution to the excessive short-termism of the UK corporate sector. They contend that, in the absence of quarterly public reporting requirements and the need to appease shareholders hungry for dividends, they are able to get more out of companies by operating them differently.

“A lot of the things that create value in the long term can be unpopular in the short term,” says Azpilicueta. That includes selling off units, and making costly investments in operations that become profitable later.

But some fear that what private equity really sees in unloved UK companies is the ability to make a quick financial return in part by selling their assets, borrowing against them or piling on debt to pay themselves dividends, a phenomenon that is on the rise in the US.

Morrisons’ freehold land and buildings had a book value of £5.8bn, its accounts for the year to January show — more than the market value of the company as a whole, before disclosure of the takeover bid caused its shares to surge.

Morrisons’ prospective new American owners have spotted an opportunity to “pick up a bunch of real estate” cheaply at a time when bargains are hard to find in the US, one adviser to the private equity industry says. Even without selling stores, owners could boost their returns by borrowing against their value, he adds.

Critics point to the collapse of Debenhams this year, which has its roots in a period of private equity ownership more than a decade ago, during which it was saddled with debt, sold and leased back its properties, and paid large dividends to its owners.

“I’m concerned about the history of private equity in retail,” in which corporate collapses have left “important anchor shops on the high street closed and often a pension fund deficit”, says Darren Jones, a Labour MP and chair of the business, energy and industrial strategy parliamentary committee.

“I understand why [private equity firms] are interested in British supermarkets,” he adds. “But these are enormous employers with tens of thousands of staff. I don’t want to end up in a situation in a few years’ time where my committee and I are having to intervene at the point of a collapse.”

Private equity “is very good at its best and very bad at its worst”, says Kay. “The kind of private equity that is squeezing margins for a couple of years before flipping the business back into public markets is . . . pretty bad.

“The kind of private equity that’s willing to stick with a business for 15 years and make a positive contribution to its growth and strategic development is a very good thing.”

One consequence of the industry’s growing role will be increasing levels of corporate indebtedness — at a time when there is growing concern about the prospect of interest rate rises and the return of inflation.

European private equity deals typically use debt of about six times a company’s earnings, figures from Refinitiv show, far higher than is common among listed companies.

The impact that private equity can have on industry is highly contested. The most significant recent study on the topic, published in 2019, found that when firms buy listed companies, employment shrinks by 13 per cent over two years. The study, which analysed private equity takeovers of US companies from 1980 to 2013, found average earnings per worker fell 1.7 per cent after a company had been bought by a private equity firm.

“We find the buyouts in general perform more poorly regarding employment than similar firms,” says Josh Lerner, a Harvard Business School professor and one of the report’s authors. However, private equity acquisitions are also “associated with large productivity gains in many but not all circumstances”, he adds.

“This mixture of consequences presents serious challenges for policy design, particularly in an era of slow productivity growth but also very substantial concerns about economic inequality.”

New rules?

Many of these arguments about the benefits and drawbacks of private equity have crystallised around the bidding battle for Morrisons.

This week Fortress wrote to the UK government offering reassurance that it would be a “supportive and responsible owner of Morrisons”. It pointed to its 2019 acquisition of Majestic Wine, all of whose stores have been kept open.

Ministers are monitoring the situation with Morrisons, but officials admit they are largely powerless to stop the takeover on existing grounds, which are limited to financial stability, media plurality, national security and public health emergencies.

Jones, the Labour MP, says it appears that “there are no teeth for ministers or regulators at all” and says they need “enforcement powers so that any commitments at the point of purchase were binding in some way . . . because the taxpayer is ultimately the backstop if things go wrong”.

The bidding war for Morrison’s comes amid a push by UK policymakers to make it more attractive for businesses, notably fast-growing tech companies, to list on the London stock market.

But management teams say this is undermined by the increasingly onerous burden of being a listed company in the UK, citing detailed pay and environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure requirements. At Morrisons, which suffered the UK’s largest investor rebellion over pay this year, management has the prospect of earning higher pay if the Fortress deal goes ahead.

One way to remove some of private equity’s advantages would be to apply some of those rules to companies that are privately held. Ministers are consulting on plans to bring larger private groups within the definition of a “public interest entity”, which demands more disclosures and director liabilities.

Nigel Wilson, chief executive of Legal and General, says the US private equity industry’s focus on the UK is an “inevitable consequence” of shortcomings in Britain’s own buyout sector. “The UK needs to build a much bigger venture and growth capital industry and use long-term capital from pension funds to support homegrown companies that are strong enough to remain independent.”

But investors warn that the raid on UK plc is likely to continue.

“By establishing this bifurcated world of highly-regulated quoted companies and unregulated private companies,” says Macpherson, the former BlackRock executive, “we’re creating the opportunity set for US private equity groups to plunder these assets that are weighed down by the weight of regulation and expectation.”

Additional reporting by Jonathan Eley, Attracta Mooney and Adam Samson

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.