There was awe in the eyes of everyone Pele ran into. He had a smile for everyone, a word here, a wave there…

| Photo Credit: Getty Images

It didn’t come as a shock, he had been slipping for a while. Yet, all death is a shock, for while there is life there is hope. Pele is not just the greatest footballer ever, he is the face of sport itself, in the manner that Einstein is the face of science and Picasso, the face of art.

Eduardo Galeano’s ‘Soccer in Sun and Shadow’.

Great sportsmen inspire great writing on sport. Here’s Eduardo Galeano on Pele: “Once he held up a war: Nigeria and Biafra declared a truce to see him play. To see him play was worth a truce and a lot more. When Pele ran hard, he cut right through his opponents. When he stopped, his opponents got lost in the labyrinths his legs embroidered. When he jumped, he climbed into the air as if it were a staircase. When he executed a free kick, his opponents in the wall wanted to turn around to face the net, so as not to miss the goal… those of us who were lucky enough to see him play received moments so worthy of immortality that they make us believe immortality exists.”

Hugh McIlvanney put it less poetically but with equal emphasis: “If all the qualities that make football irresistible to countless millions have ever been embodied in one supreme player, that man is Pele.” He wrote that in 1990, after Diego Maradona had led Argentina to two successive World Cup finals, winning in 1986.

Interacting with Pele was probably the highlight of a mid-career shift to Dubai I made in the 90s. When we met, my books not having arrived yet from India, he signed the one I had — now the only cricket book signed by Pele! His guiding principle seemed to be: thou shalt not disappoint.

I had gone to the airport to meet him, and was startled at how little space he occupied. He wasn’t more than 5’8”, but had a combination of sturdiness and balance. His hooded, sleepy eyes spoke of a man thoroughly relaxed, an image he projected even in his playing days.

We shook hands on that occasion — by the time we said goodbye a day-and-a-half later, he was treating me like an old friend, and nothing short of an embrace would do.

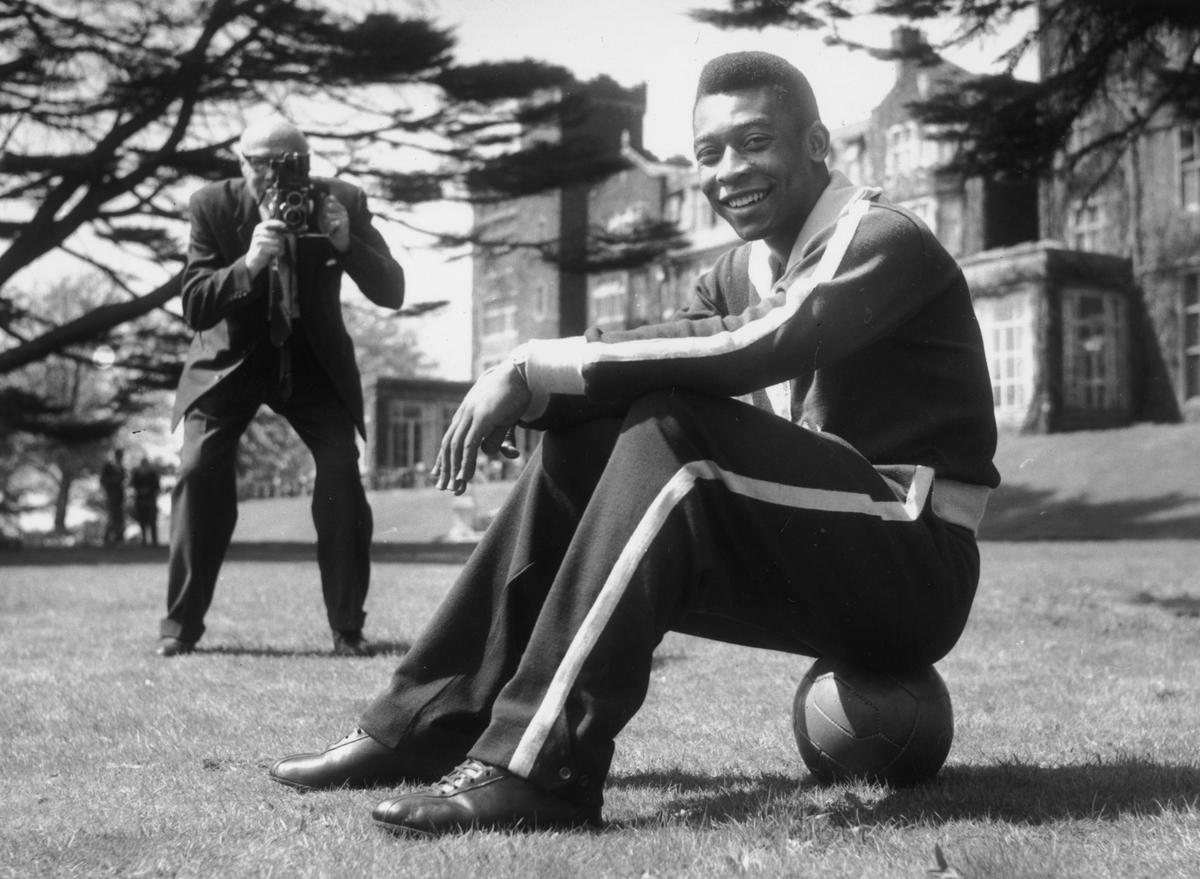

Pele: the most recognised face on earth

There was awe in the eyes of everyone he ran into, from the tea-boy to officials everywhere. Pele didn’t accept this as merely his due, nor did he avoid eye-contact. He had a smile for everyone, a word here, a wave there. Decades of being the most recognised face on earth hadn’t sharpened his craving for privacy.

Pele takes a break from training, in England, 1963.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

He had trademarked his name — only Coca Cola had greater brand recognition around the world. I asked Pele if he ever tired of signing autographs and posing with fans. “I believe I was put on earth to make people happy,” he said. It sounded trite at first, but through that meeting and others, I realised he really felt that way.

Pele (10) shakes hands with boxer Muhammad Ali before a game at Giants Stadium, New Jersey, U.S., 1997.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

“You and I are the greatest,” boxer Muhammad Ali told Pele when they met. Pele was criticised for lacking Ali’s political consciousness and for not doing enough for blacks. For years, when Pele was the best-known Brazilian, his country was ruled by the dictator Emilio Medici. There were human rights abuses, persecution of dissidents, media censorship, but Pele didn’t speak out; he was photographed with the rulers. Ali, younger than Pele, had lost three years at his peak for standing up to the U.S. government and refusing to fight in Vietnam.

But it was the same Medici who convinced Pele to play in the 1970 World Cup after the player had decided not to. He had been hacked down in 1962 and 1966 by defenders given the task of doing exactly that. Not yet 30, in 1970, he gave the world some of the greatest exhibition of goal-scoring and goal-assisting.

Pele’s famous ‘no-look’ pass

Goals not scored by Pele took on legendary status too. Against Czechoslovakia, he noticed the goalkeeper off his line when the action was in the Brazilian half and unleashed a huge drive that had him desperately flailing as the ball narrowly missed the goal. Against Italy, he set up a goal for Carlos Alberto with his famous ‘no-look’ pass, sending the ball to his right where no one else had seen an advancing Alberto who then scored. Pele could have scored himself, but Alberto had a free run.

The French footballer (and occasional poet) Eric Cantona said of that pass: “I will never find the difference between the pass from Pele to Carlos Alberto and the poetry of the young Rimbaud.”

Pele had a relationship with the football that was unique, and went beyond mastery. The football was part loyal friend, part dancing partner, part mate in mischief. It obeyed his loudest instructions and gentlest whispers. Pele was fiercely competitive but this didn’t affect his sheer joy at playing the game. Sometimes he did things simply because he could.

It meant he occasionally pushed the ball between an unwary defender’s legs or bounced it off his shin to change its course. It was a tribute to his sense of fun. The beautiful game could be enjoyed at many levels.

At a training session in Dubai, noticing (out of the corner of his eye while he was speaking to some officials — that ‘no-look’ again) that a player was slow to the ball, he turned to me and said, “If you have a talent, you have the responsibility to keep fit.” He could have been speaking for athletes in general.

A couple of years later we met again. This time I had his autobiography, My Life and the Beautiful Game. Pele signed on the title page by right. It was one of the first books on soccer I had bought.

Let the artist Andy Warhol have the last word: “Pele was one of the few who contradicted my theory: instead of 15 minutes of fame, he will have 15 centuries.” Exaggeration is the first test of greatness.

The writer’s latest book is ‘Why Don’t You Write Something I Might Read?’.

For all the latest Sports News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.