Oppenheimer’s big screen odyssey: The man, the book and the film’s 50-year journey

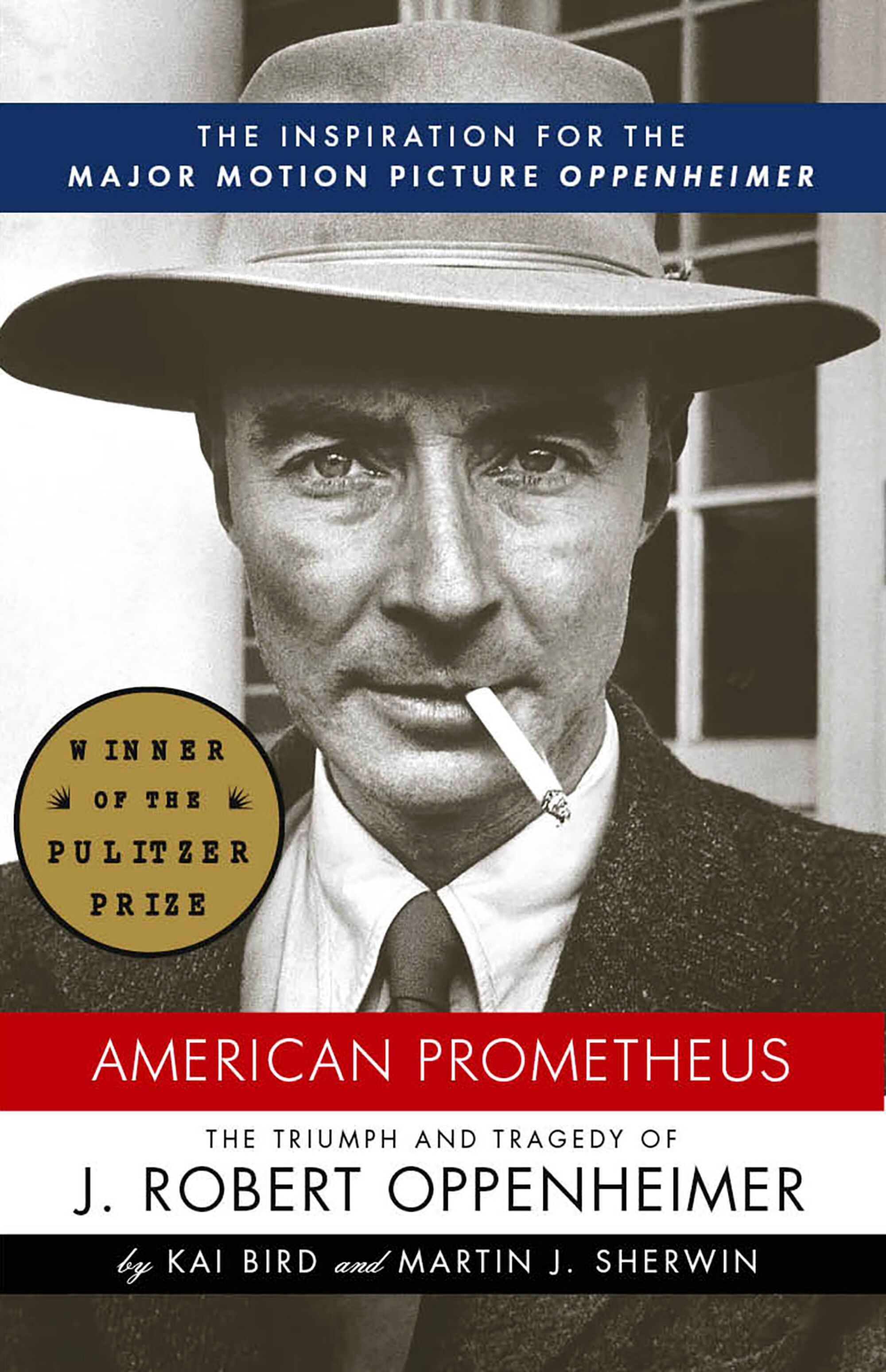

Among the many astonishing facets of Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” is the speed at which the movie came together. In early 2021, the director read “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” a sweeping biography by Martin Sherwin and Kai Bird of the physicist known as the father of the atomic bomb. Riveted, Nolan immediately began adapting it into a screenplay. Less than a year later, he was filming. The movie, among this summer’s most anticipated, premieres on Friday.

But that’s only half the equation. By another metric — befitting one of history’s most complex figures and a filmmaker drawn to labyrinthine narratives — the adaptation of “Oppenheimer” can be seen as a multigenerational saga nearly half a century in the making. Nolan’s epic movie builds on an epic book with an epic industry backstory. The writing of “American Prometheus” took 25 years, and since its publication in 2005, the book had been floating through Hollywood like an atom no one could figure out how to split: always under option, never moving past development.

This origin story begins in 1980, when Martin Sherwin, then 43, signed with Knopf to write a biography of Oppenheimer. Marty, as everyone called him, poured himself into the research, taking his family on a trip to New Mexico to meet Oppenheimer’s reclusive son, Peter, and tracking down just about every living person who had known the scientist. In time, Sherwin amassed some 50,000 pages of declassified government documents outlining Oppenheimer’s years as director of the Los Alamos lab and the subsequent loss of his security clearance during the panic of McCarthyism.

What Sherwin did not do, however, was sit down and write.

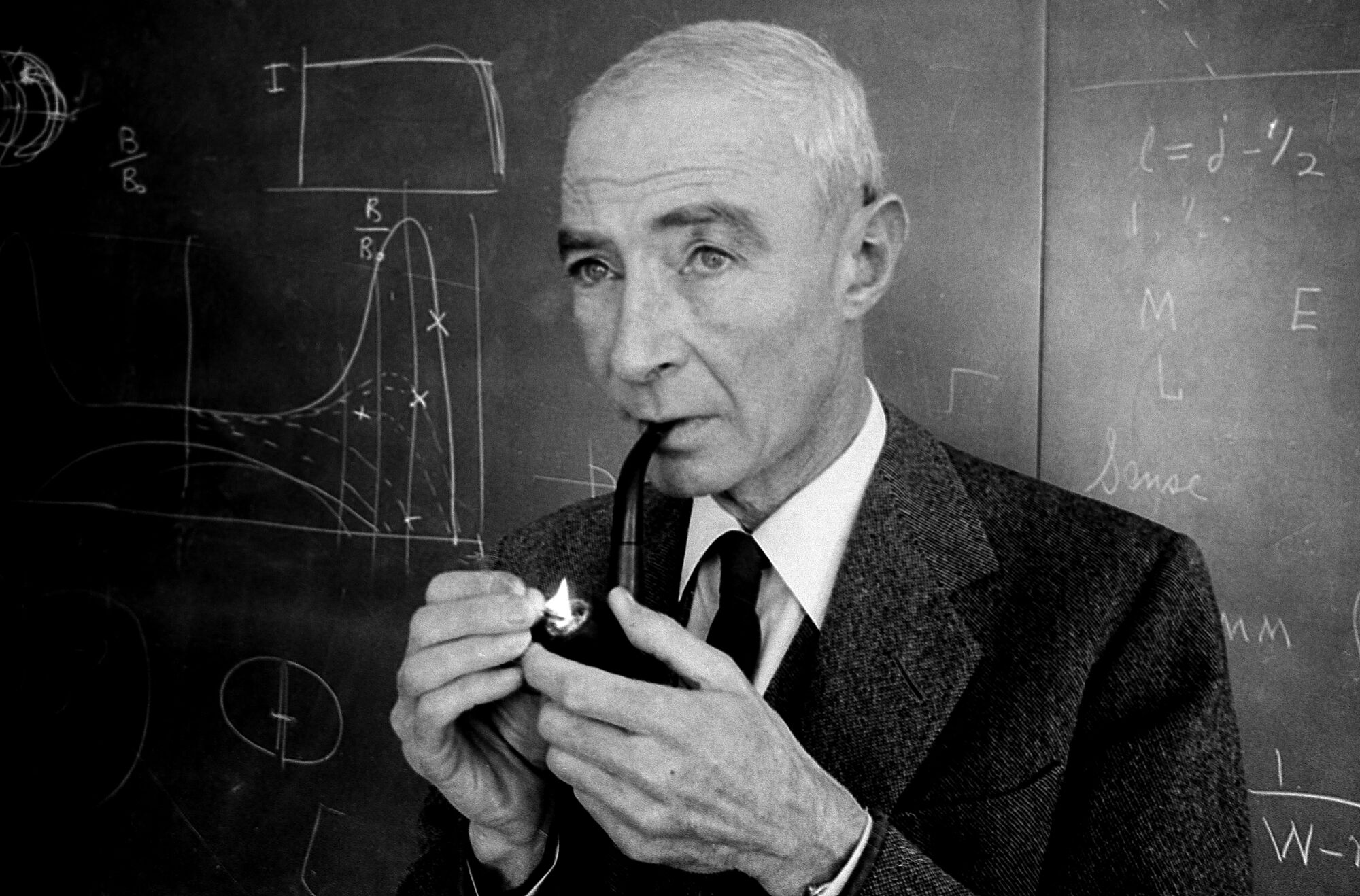

J. Robert Oppenheimer, creator of the atom bomb and subject of a magisterial biography and now an epic film, at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., on April 5, 1963.

(Eddie Adams / Associated Press)

A singular collaboration

The deadline came and went, many times over. Sherwin’s son, Alex, recalls his father’s unwritten book as a subject of frequent ribbing at the dinner table of the family’s Boston home. “It was a great source of pleasure,” Alex said in a recent conversation. “He would say to me, ‘Do your homework,’ and I would say, ‘Write your book!’ He had a great sense of humor about it.”

Far from the cliché of the tortured writer, Sherwin was, if anything, diverted by his own rabid enthusiasm. He took a professorship at Tufts University, where he established the Nuclear Age History and Humanities Center. Presaging the internet era, Sherwin pioneered what he called a “space bridge,” using a satellite during the late 1980s to hold live discussions between his classes and those at Moscow State University. He also wrote numerous essays and op-eds about the nuclear age.

But by the late 1990s, nearly 20 years behind schedule on his book, Sherwin’s attitude toward the project became less sanguine. “At several points, the light at the end of the tunnel got very dim,” he later noted to an audience at a book fair. His wife, Susan, recalled in an interview that Sherwin began remarking that he was going to take the book to the grave.

“That became his joke,” she said, “that it would be on his tombstone.”

Sherwin came up with a bold solution: He would bring in a partner on the project — specifically, his friend and fellow historian Kai Bird. The two had met in 1980 and grew close in 1995, when both were involved in addressing a divisive Smithsonian exhibit of the Enola Gay, the plane that released Oppenheimer’s bomb over Hiroshima in August of 1945. (When the plane was again exhibited in 2003, they co-authored an op-ed for The Times about it.)

While Bird was intrigued by the subject, he didn’t immediately warm to the idea of working together.

“I told him no — that I liked him too much,” recalled Bird, whose first book had begun as a collaboration with a friend that ended acrimoniously. Bird’s wife was adamant that he not take on another.

Sherwin was undeterred. Over the next six months, he traveled regularly from Boston to Bird’s home in Washington, D.C. “He seduced the two of us into thinking this was a good project,” said Bird. The two wrote a proposal, and Knopf agreed to a new contract in 2000 — offering them a book advance that came to $290,000 (after subtracting $35,000 paid to Sherwin in 1980). Bird recalled that Sherwin gave him a “bigger chunk” of the money since the book would be Bird’s sole income.

“Part of Kai and Marty’s story is the story of something that’s been lost in the publishing,” said Susan Sherwin. “The industry had a willingness to nurture people and projects in a way that’s kind of unimaginable today.”

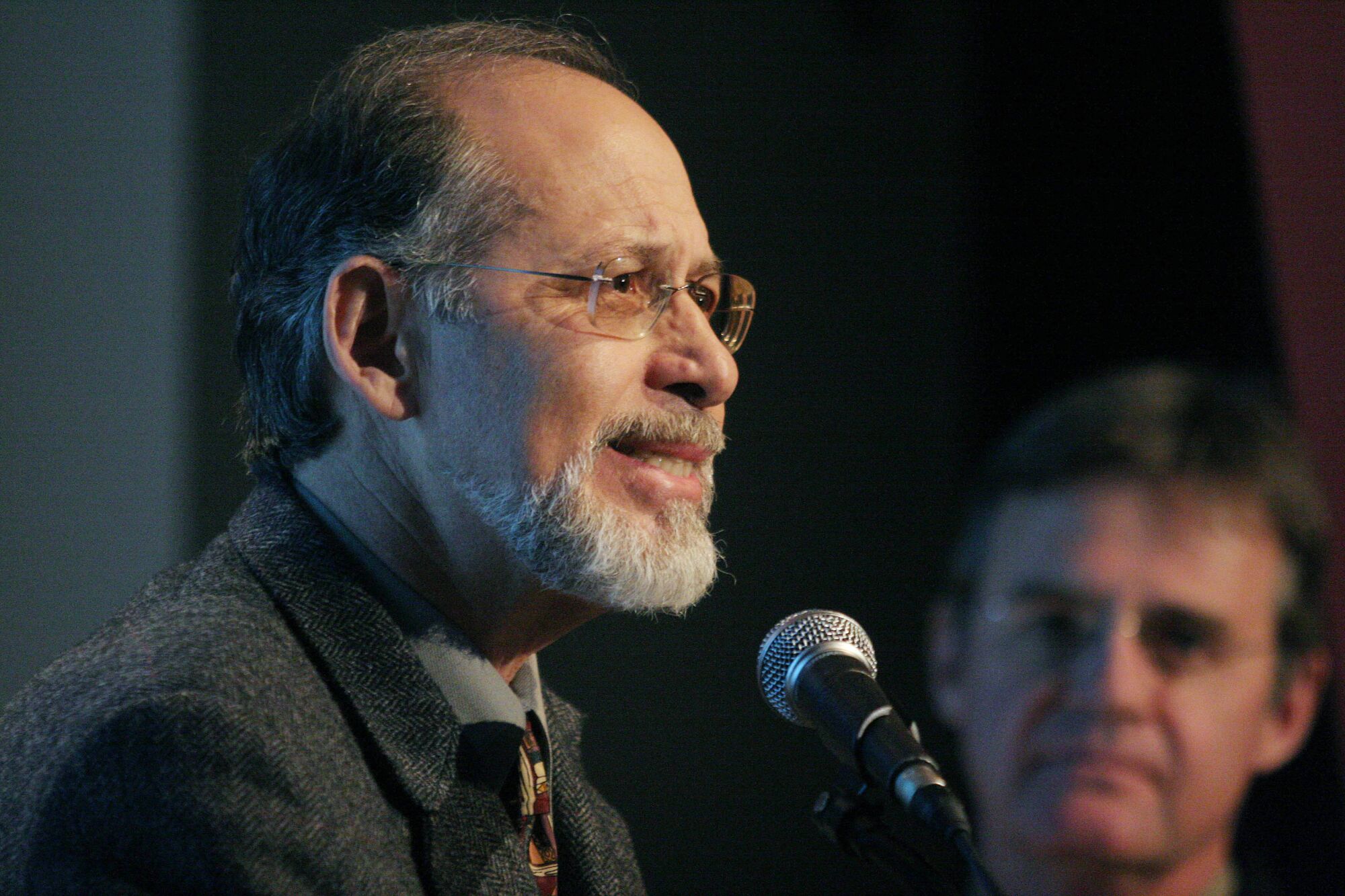

Martin Sherwin, left, speaks as Kai Bird stands by, accepting a National Book Critics Circle prize for their biography “American Prometheus” in 2006.

(Tina Fineberg / Associated Press)

The men celebrated the deal with martinis, christening the project with the same toast favored by Oppenheimer with the scientists of Los Alamos: “To the confusion of our enemies!”

Over the course of four years, they volleyed chapters back and forth to produce what became “American Prometheus,” a 721-page biography that is both grand in scope and granular in personal detail. Rapturously reviewed in 2005, the book won a Pulitzer Prize, an honor the writers took as a tribute to their singular collaboration.

A movie Marty would have loved

Immediately following its publication, the book seemed to be on a fast track to becoming a movie when Sam Mendes, the director then known for “American Beauty” and “Jarhead,” optioned it.

“We were very excited and completely naive,” said Susan, describing a familiar story of Hollywood entropy: unbridled enthusiasm morphing into development snags before petering out completely. Though the book continued to spark interest and remained under option by various producers, its authors stopped believing a movie would ever emerge.

“We acquired what you could call a more jaundiced view of Hollywood,” Bird said.

Christopher Nolan, left, and Cillian Murphy on the set of “Oppenheimer.”

(Melinda Sue Gordon / Universal Pictures)

Then in September of 2021 — 40 years after Sherwin started the book and 16 since it was published — a friend of Bird’s sent him a curious item in Variety noting that Nolan’s next project would be about Oppenheimer. Bird and Sherwin had heard nothing about this. “I assumed maybe he was using a different book, or just going from the public record,” Bird said.

But Nolan was indeed basing his movie on “American Prometheus,” thanks in part to the tenacity of someone who had never worked in Hollywood. Since 2015, the film rights had been under option by J. David Wargo, a successful New York businessman who studied physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and was itching to get into movie production. Various scripts had been commissioned and rejected.

“Then, during the midst of the pandemic, Wargo got frustrated with the project and flew out to L.A. on a rented private plane and went to Hollywood,” Bird explained. Wargo met with Charles Roven, one of Nolan’s longtime producers, who handed the book to the director.

As it happened, Nolan had recently completed “Tenet,” a movie that references the atomic bomb, and one of its stars, Robert Pattinson, had given the director a book of Oppenheimer’s speeches as a wrap gift.

“I’m always pushing various things forward, but this is one where a lot of different planets aligned,” Nolan explained during an interview, recalling the particular scene from “American Prometheus” that hooked him: “Los Alamos, this place that will always live in history or infamy, was first a place where Oppenheimer and his brother loved to go camping. Suddenly, like a bolt from the blue, I’m looking at the most personal possible connection between a character and a massive change to the world that couldn’t be undone.”

“It was all very slow,” said Bird, “until suddenly one day it wasn’t.”

That fall, Nolan called Bird, asking if he and Sherwin could come up to New York from D.C. (where Sherwin had also moved) to meet with the director. Sherwin, then 84, was at that point too weak to travel. Two years earlier, he had been diagnosed with small-cell lung cancer.

Cillian Murphy as Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer in a scene from “Oppenheimer,” left, and the real Oppenheimer on the test ground for the atomic bomb near Alamogordo, N.M., on Sept. 9, 1945.

(Universal Pictures; Associated Press)

“We met for two and a half hours, and Nolan humored my probing about the project,” Bird said. “But he made it clear that he worked confidentially and was not sharing the script.”

Nolan, for his part, found their meeting quelled some of his own jitters about the adaptation.

“One thing Kai said to me which gave me an enormous sense of confidence was that he believed any film should be framed around the security clearance,” said Nolan, whose script and final film is structured around that drama. “I breathed a large sigh of relief knowing he wouldn’t think I’d done anything so radical.”

Bird, after raising a glass to Nolan and toasting him with Oppenheimer’s words — “To the confusion of our enemies!” — was able to extract one kernel about the film.

“Did that line make it into the script?” he asked Nolan.

“It was in there,” the director said, “but I had to cut it for space.”

Back in Washington, Bird rushed over to Sherwin’s home to tell him about the meeting. “He was gratified,” Bird recalled, “but still skeptical.”

Two weeks later, on Oct. 6, 2021, Sherwin passed away.

Those closest to him have spent the last year savoring the making of “Oppenheimer” on his behalf. Susan and Alex Sherwin spent a day on the film’s set in Princeton, N.J., where they met Cillian Murphy, who plays Oppenheimer, and were startled to see in 3-D a version of the world Marty had dedicated so much of his life to researching.

Just before filming, Nolan let Bird read the script, putting the writer up in a downtown Manhattan hotel and waiting in the lobby for him to finish. Bird was struck by how faithful it was to the book, capturing what was always most important to Sherwin: the paradoxes at the heart of Oppenheimer’s character and the intimate details that dovetailed with enormous plate shifts of world history.

“He died knowing it was in the works, but it’s sad that he can’t be here to see the hoopla,” said Bird. “Marty would have loved it.”

Amsden is a writer based in Los Angeles.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.