Omicron cases less likely to require hospital treatment, studies show

A lower share of people infected with the Omicron coronavirus variant are likely to require hospital treatment compared with cases of the Delta strain, according to healthcare data from South Africa and Denmark.

The findings by separate research teams raise hopes that there will be fewer cases of severe disease than those caused by other strains of the virus, but the researchers cautioned that Omicron’s high degree of infectiousness could still strain health services.

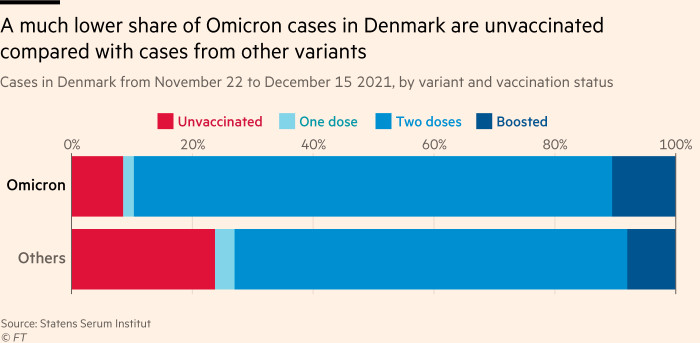

The reduction in severe illness was likely to stem from Omicron’s greater propensity, compared with other variants, to infect people who have been vaccinated or previously infected, experts stressed.

Unvaccinated groups remained the most at-risk but as the vast majority of breakthrough infections and reinfections caused by Omicron are mild, the proportion of all cases that developed severe disease is lower than with other variants. The strain now accounts for a majority of Covid-19 cases in several countries, including the US.

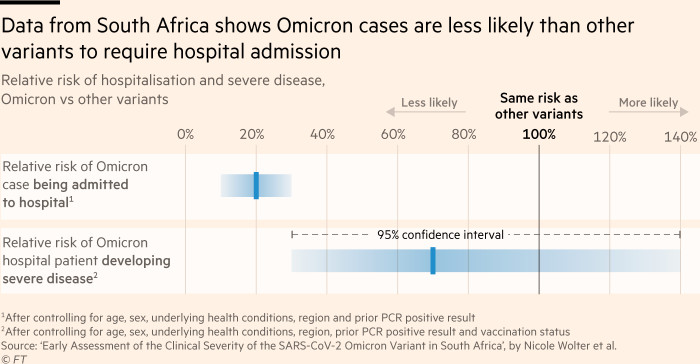

The South African study, carried out by the country’s National Institute For Communicable Diseases, found that among people who tested positive during October and November, suspected Omicron cases were 80 per cent less likely than Delta cases to be admitted to hospital, after adjusting for factors including age, underlying health conditions and previous infection. But researchers stressed they did not account for vaccination status in this analysis, and data on prior infections were unreliable.

A second analysis from the same research team, this time controlling for vaccination status, found that once admitted to hospital, Omicron and Delta cases from recent weeks had a similar likelihood of progressing to a serious condition. The analyses included more than 10,000 Omicron cases and more than 200 hospital admissions.

“There is something going on . . . in terms of the difference in the immunological response for Omicron vs Delta,” said Prof Cheryl Cohen, an epidemiologist at the University of Witwatersrand and one of the study’s authors.

She said the findings suggested that breakthrough infections and reinfections from Omicron were “less severe” and that immune protection from T-cells and B-cells “mediated” Omicron’s “progression to severe disease” despite the fall in antibody protection.

Cohen said the reduced burden on hospitals had allowed South Africa to handle the Omicron wave without imposing a lockdown but she cautioned that the findings may not be applicable to western nations with older populations.

“It’s about what [Omicron] means in terms of absolute numbers as, if the numbers are so big, it can still cause a substantial public health problem even if per case the risk of severe disease is less,” she added.

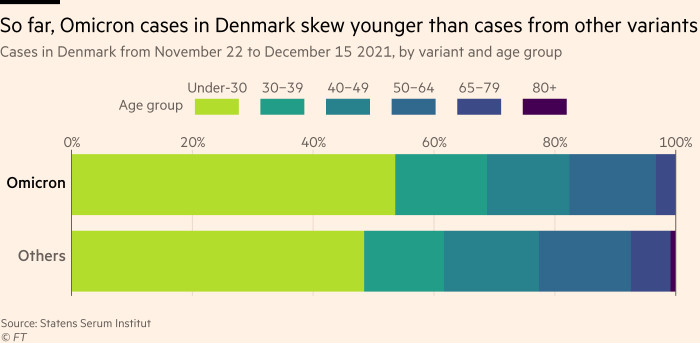

Separately, Danish data showed that among people who tested positive between November 22 and December 15, Omicron cases were three times less likely to be admitted to hospital than cases with other variants. But experts warned that the concentration of Omicron outbreaks among younger groups could skew the data.

“It is primarily young and vaccinated people who are infected with Omicron, and when we adjust for this, we see no evidence that Omicron should result in milder disease,” said Henrik Ullum, director of the Statens Serum Institut, Denmark’s public health agency, in a press conference on Wednesday.

But while there is no evidence yet for any intrinsic reduction in severity, this does not preclude Omicron resulting in less severe outcomes at the population level, due to a greater share of cases being among people with some protection against severe disease through either prior infection or vaccination.

“Due to Omicron’s higher immune evasion, this pattern [of fewer cases being hospitalised] will persist in a population-level assessment,” said Prof Samir Bhatt, professor of machine learning and public health at the University of Copenhagen and a member of the UK government’s SPI-M modelling group.

The UK government is awaiting fresh data on the severity of Omicron before deciding on further restrictions in England. But Bhatt said the UK approach was “Panglossian”, adding that it “overstates the hope offered by reduced severity”.

“I feel that the build-up of hospital pressures will be slower and lesser because the vaccine seems to still be protective,” said Prof Thea Kolsen Fischer, head of virus and microbiological specialist diagnostics at the Statens Serum Institut.

But she added that policymakers should be a “little careful about making the narrative that it’s more mild” because it would be “some weeks” before the variant’s impact on hospitals becomes clear.

“I fear that because of the infectiousness of Omicron . . . what we see right now will be very different in just about two weeks’ time,” she said.

On Sunday, Denmark introduced a suite of measures to contain Omicron’s spread, including the closure of theatres and museums and capacity limits in bars, restaurants and shopping centres.

Prof Peter Garred, a clinical immunologist at Copenhagen’s Rigshospitalet, the largest hospital in Denmark, said a drop-off in severity could make the decision of countries, such as England and US, not to impose restrictions “just about tenable”.

“The question of whether Omicron is mild or not has not really fed into the discussion about new restrictions [in Denmark],” said Garred. “The government is foreseeing problems because the infection rates are increasing so dramatically, regardless of severity.”

University of Witwatersrand’s Cohen said the Omicron wave could “pan out differently” in the northern hemisphere because of it coinciding with winter but she added that the positive signs from South Africa had “a lot of relevance to other countries and how they respond”.

“Most populations have either previous infection or vaccination or both at this point,” said Cohen. “If it holds up, it is likely true that all countries will see a similar effect to us.”

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.