Naveen Kishore’s ‘In a Cannibal Time’: The dark (and light) unleashed

Naveen Kishore’s In a Cannibal Time is a show of reverence. It treats theatre like a monolithic goddess, remembering the past and foretelling the future to anyone who cares to listen. In this case, through the lens of self-taught photographer (and founder of Kolkata-based publishing house Seagull Books) Naveen Kishore’s recording of four styles of theatre, over the course of the last quarter of a century.

Naveen Kishore

| Photo Credit:

Emami Art

The photographs — currently on exhibit at the gorgeous Kolkata Centre for Creativity, at Emami Art, in collaboration with Chatterjee & Lal — are from four of Kishore’s significant bodies of work: The Epic and the Elusive (1997), Performing the Goddess (1999), In a Cannibal Time (2002), and The Green Room of the Goddess (2003). It documents what it means to be caught in a holocaust of trauma, to be victims, to be broken and remade. As curator Ranjit Hoskote explains: “In his various works, Kishore never loses sight of the anguish and the exhilaration of the human adventure. The mandate of testimony, the urgency of bearing witness to ideologically fraught and emotionally demanding histories, is central to his work.”

Naveen Kishore with Ranjit Hoskote

| Photo Credit:

Vivian Sarky

Makers of life, drama and goddesses

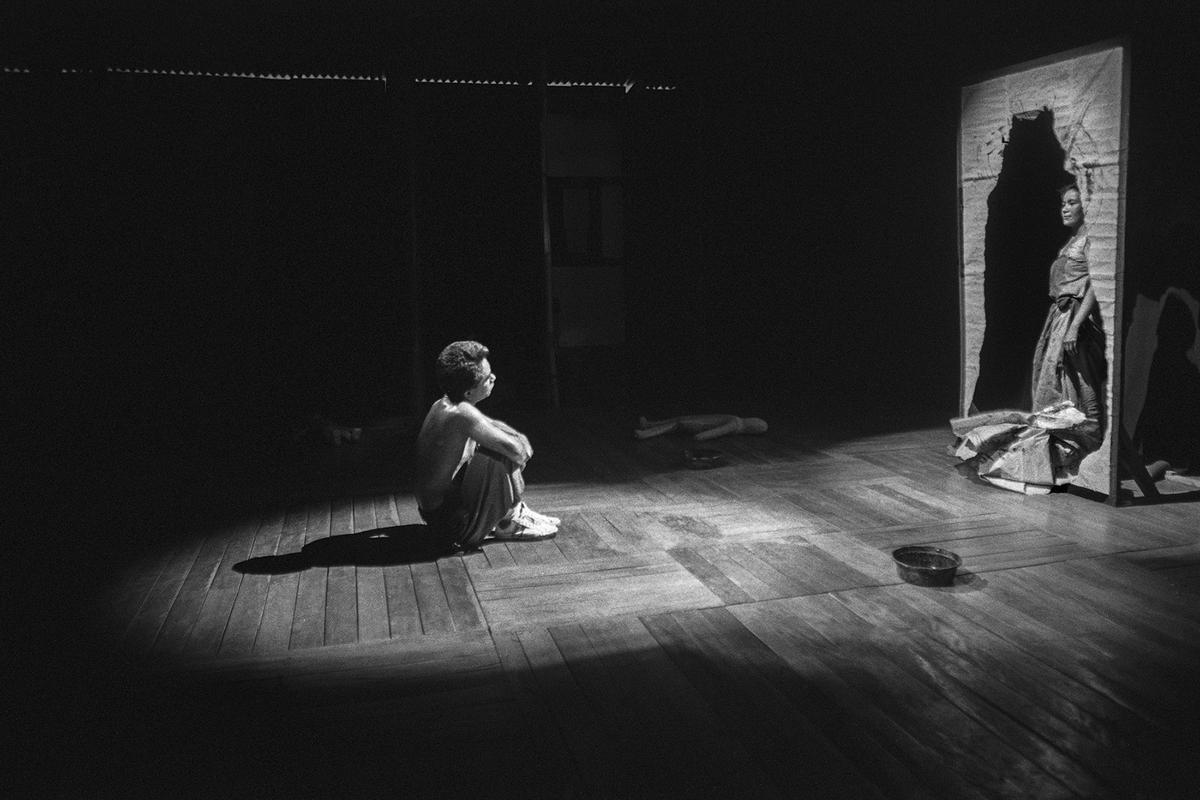

The Manipur theatre series, The Epic and the Elusive, is especially evocative, given the current situation in the state as well as the history of warfare its people have faced — both with the government of India for 50 years, and the repeated episodes of violence among the ethnic groups in the State. Kishore captured the powerfully present actors when he and editor-playwright Anjum Katyal were documenting the work of various theatre groups in Manipur during a time of political unrest.

The Manipur theatre series is especially evocative, given the current situation in the state as well as the history of warfare its people have faced

| Photo Credit:

Vivian Sarky

A photo from The Epic and the Elusive series

| Photo Credit:

Emami Art

Performing the Goddess, or the Chapal Bhaduri series, is his most famous. It also made a living legend of Chapal Bhaduri, the last female impersonator in Bengali jatra (street theatre), who performed under the name Chapal Rani. As actors such as Moon Moon Sen started performing in jatras in the ’70s, he fell into obscurity, till the only role he could find was playing Shitala Mata — the incarnation of Goddess Parvati that cures pox — in four-hour-long performances for 50 nights in a year.

Performing the Goddess, or the Chapal Bhaduri series, is Naveen Kishore’s most famous

Interspersed are photos from The Green Room of the Goddess, depicting the creation of pujo idols in Kumartuli, the warren of tiny lanes in north Kolkata that is both home and workshop to artisans, potters and artists. One catches glimpses of Kali standing astride Shiva in the frames, garlands of hands covering waists, partially-painted faces of the goddess, disembodied heads, workers, and structural debris. As Mortimer Chatterjee, of Chatterjee & Lal, says as an introduction to the show, “Kishore emotes through his photography — whether it’s an inanimate mannequin or an actor. He is able to tease out incredibly intense moments of action and dynamism.”

Pujo idols in Kumartuli

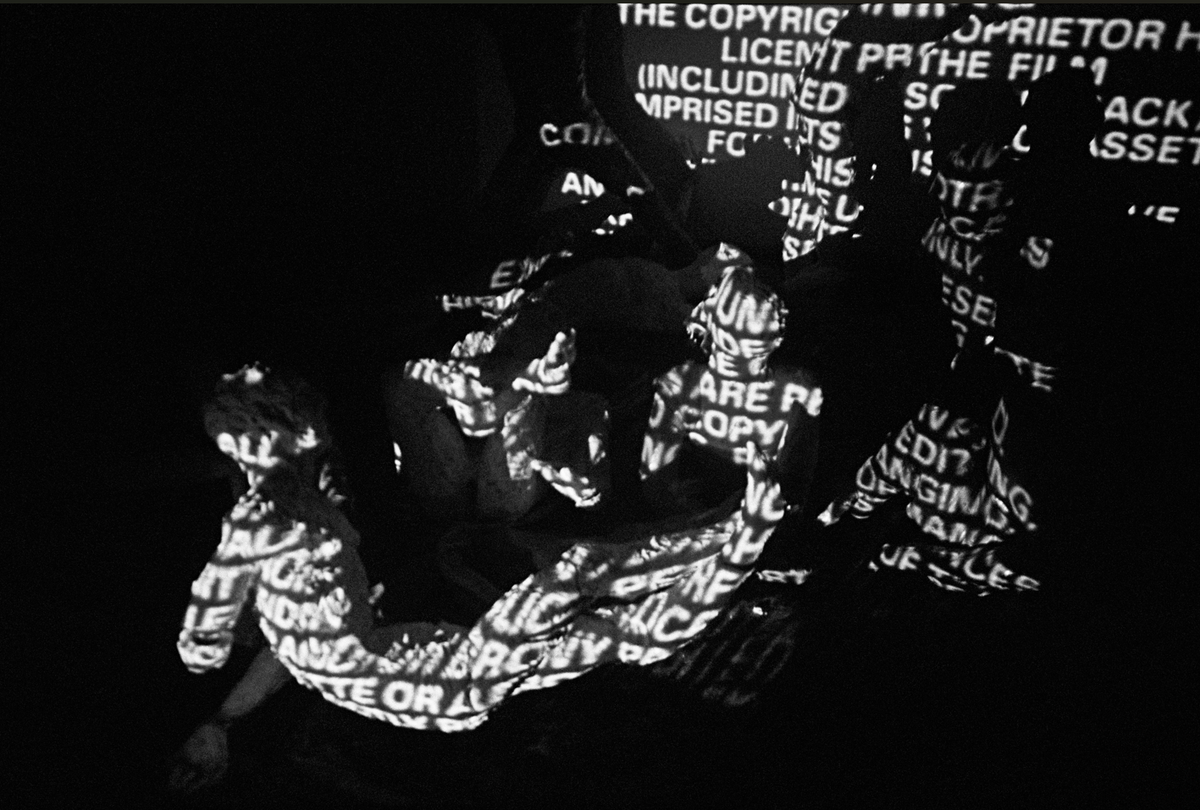

The last series, which lends its name to the exhibition, was created in 2002. In January that year, artist Tom Lai designed the Seagull Book Stand for the Calcutta Book Fair, using a series of life-size faceless and genderless clay statues from Kumartuli. They were situated in various aspects of suffering and captivity, expressing the lack of agency allowed to the common people. Later that year, Kishore re-used the statues — this time placed against light, smoke and projections in a theatrical shoot — to comment on what the genocide in Godhra portended for India.

In a Cannibal Time

Naveen Kishore used life-size faceless and genderless clay statues to comment on what the genocide in Godhra portended for India

‘The non-doing exhausts’

Given Kishore’s decades-old interest in theatre and lighting, In a Cannibal Time is a masterclass in the use of lighting and space. The size of the photographs (they were blown up for the first time to around 22×30 inches because the space allowed for it) impresses when you first walk in, along with the usage of colour in the Goddess series versus the black-and-white in the Manipuri theatre and Cannibal series.

The lighting is muted, too. “I’ve kept it at 70% intensity,” says Kishore. “Each photograph has its own light source, either daylight or artificial light.” The overall effect is that of a subdued whisper.

In a Cannibal Time is a masterclass in the use of lighting and space

| Photo Credit:

Vivian Sarky

‘Cannibal times have happened throughout history’

| Photo Credit:

Vivian Sarky

Kishore maintains the objectivity required of a photographer who must “select frame after frame of anguish, print and install it and invite others to see, feel and remember”. But why ‘a cannibal time’? (It is believed that by the end of Kali Yuga, people will lose track of their common sense and their moral compass, and resort to cannibalism). “It’s not new. Cannibal times have happened throughout history,” he shares. “[Historian] Dr. Romila Thapar will tell you that; Hannah Adams’ dark times have happened. [Playwright-poet Bertolt] Brecht talks about it. In my head, somewhere, cannibal times are more appropriate today. The dark times seem almost romantic and less threatening.”

‘Don’t you get tired of caring, given the cyclical repetition of dark times,’ I message Kishore later. “The caring is intuitive. One cannot create without caring. The non-doing exhausts,” he WhatsApps me back.

In a Cannibal Time ends on June 25.

The writer is the author of a fantasy series, and an expert on South Asian art and culture.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.