Mixed media artist Pamela Smith Hudson was told to ‘stay in one lane.’ She refused

In her early years as an artist, Pamela Smith Hudson often heard a familiar refrain: Stick to one medium. “I was told that ‘you’re either a printmaker or a painter: Stay in your own lane. Stay in one lane,’” Hudson recalls. Instead, she had another idea: Why not merge disciplines together, combining techniques and artistic forms to create her own unique mixed media? So she did. “I didn’t listen to them,” she says. “I’m glad I didn’t.”

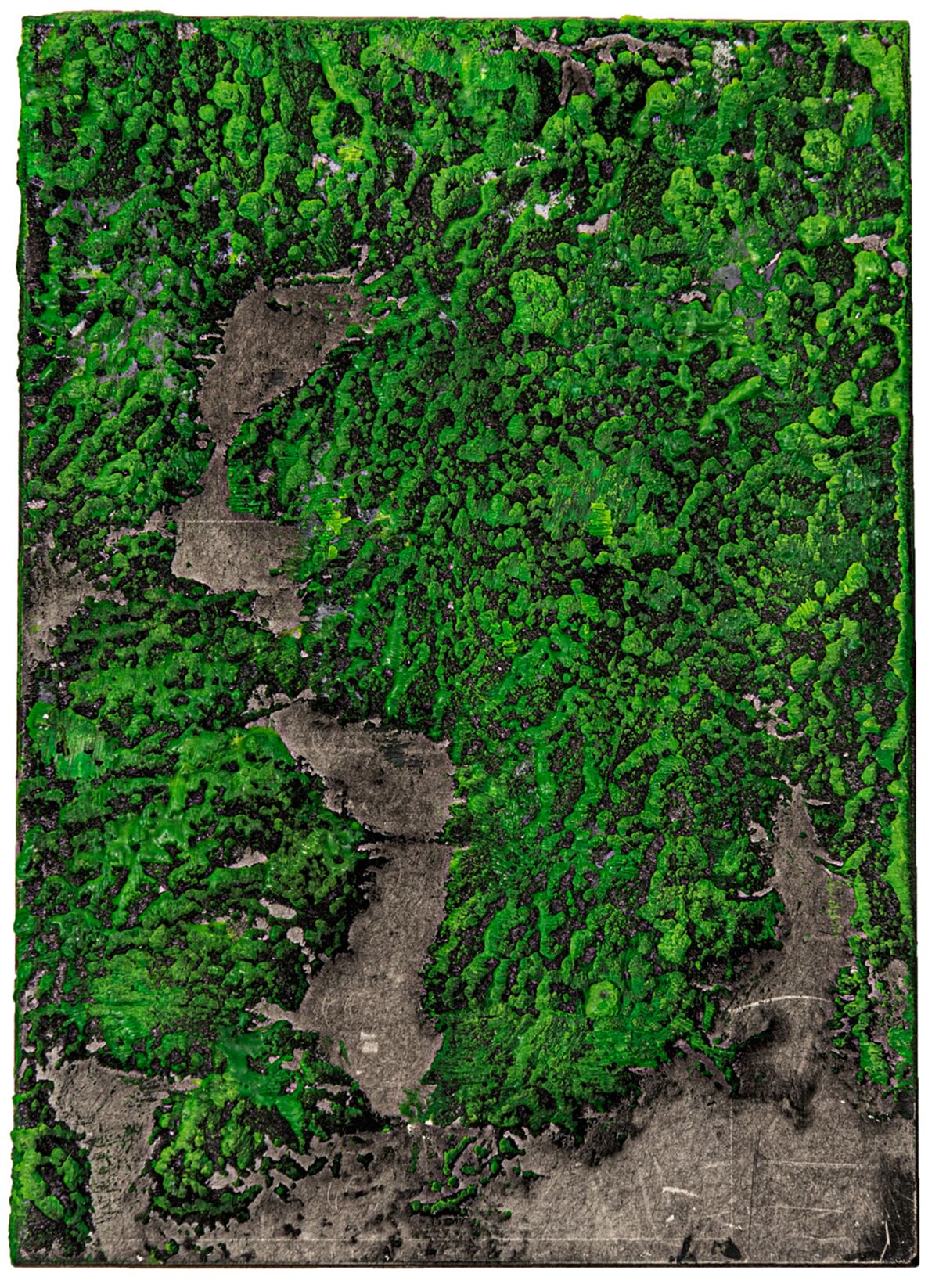

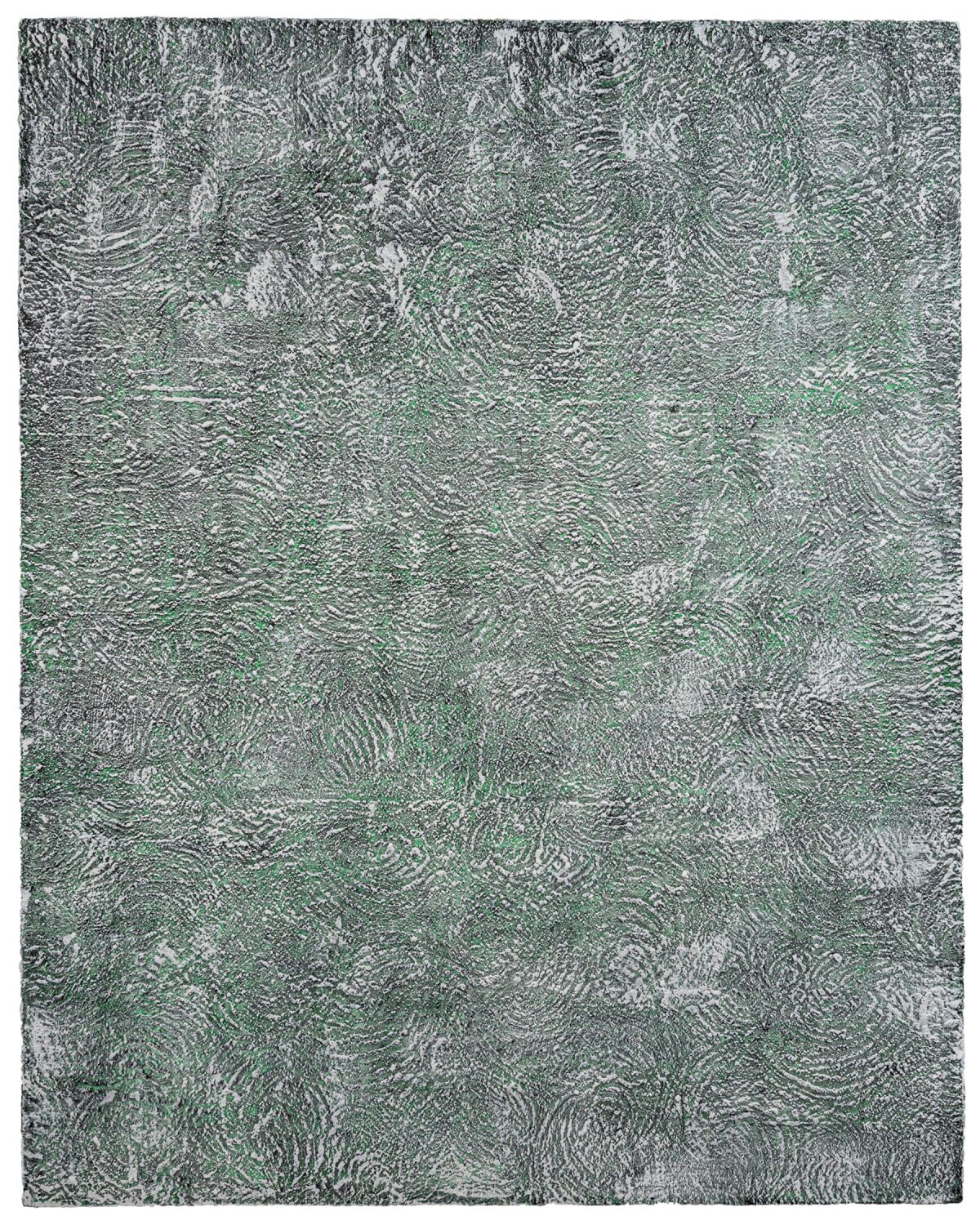

The artist’s current solo show, “Empty Space” at Craig Krull Gallery, features abstract mixed media with limited palettes . The pieces include clear nods to the natural environment while also creating a feeling of being transported. The mixed media works often echo the texture of sand or craters, bringing to mind sidewalks or striations. The Earth-like feel of many pieces comes from Hudson’s experimentation with materials like clay, graphite, watercolor and encaustic elements.

“Big Green,” encaustic mixed media on panel, 5×7, 2022.

(Erick Cortes)

Growing up in Compton, Hudson was used to seeing “mortar, plaster, grout” and other materials in her backyard. Her father was a cement mason. Her mother was a nurse and a “wonderful seamstress” who made hats and jewelry — Hudson later learned that she used to paint, but stopped when she had kids. Music often drifted throughout the house, especially since all the kids played instruments (Hudson played the clarinet and oboe). All these elements would later come to influence Hudson’s work as an artist. Much of her work is encaustic mixed media; the method uses heat, wax and pigments in a manner that traces back to ancient civilizations.

The importance of cultural identity and community-building was clear to Hudson from a young age. She says her sister took her, as a kid, to the Black Panthers’ breakfast program. Compton, in the ‘60s and ‘70s, buzzed with the energy of the civil rights movement. Hudson also spent a lot of time with her maternal grandmother, whose mother was Choctaw and grew up on a reservation. “Her saying was always, ‘I make good cornbread and I make good fry bread,’” says Hudson. The mixed-media pieces “Rain Dance 1” and “Rain Dance 2” pay homage to her grandmother and to the artist’s Afro-Indigenous roots (which come from both sides of the family). Before crafting her art practice, however, Hudson started on a very different path. As a student at Centennial High School, she was part of the Medical Counseling, Organizing and Recruiting program (Med-COR), with the goal of working in medicine. Hudson ultimately enrolled at UCLA as a biology major.

“Rain Dance 1,” encaustic mixed media on khadi paper, 22.5×30, 2023.

(Erick Cortes)

On campus, though, she gravitated toward peers working in the arts, from dance majors to film students. Here was a world beyond science — Hudson took art history classes, interned at the Museum of Cultural History (now the Fowler Museum at UCLA) and went on archaeological digs. She changed her major to anthropology, shifting her focus from a traditional career to one in the humanities.

After graduating, Hudson visited friends in Berlin and Oxford, England, taking in as much art as she could and attending the Documenta art fair in Kassel, Germany. There, she started to think more about environmental issues, learning that Europe was ahead on systems like water conservation and recycling.

Back in the States, Hudson spent many of her days in stores like Graphaids Art Supply and Zora’s (a now-shuttered store run by late art materials specialist Zora Sweet Pinney and her husband, Edward). The artist saw few women of color working for major art supplier companies, and her curiosity for the field grew as she spoke with chemists and learned more about the field.

“I had access to how these materials were made,” says Hudson. “That’s the science part. I loved it, I loved materials. So that just fueled me to explore so many different types of materials in my work — working with wax and encaustics and all kinds of materials, and experimenting with putting them all together.”

“Little Green,” collage of watercolor, graphite and encaustics on panel, 48×60, 2023.

(Erick Cortes)

Suzanne Temp, a painting teacher, first suggested that Hudson work with printmaking. Soon, Hudson started an apprenticeship with Dan Freeman, of Freeman Editions and Gemini G.E.L. He urged Hudson to look at Jasper Johns’ work, which used encaustics — something that Hudson began to explore more closely.

Through the years, Hudson has woven her fascination with Los Angeles into her work. Hudson uses “images of prints of tire tracks” to highlight the emphasis on cars in the city; the tracks, she says, “almost look like ancient symbols of displacement.” Hudson often reflects on how there’s “less land and open space” in the city.

“Gouge Away 12,” clay on clay panel with dry pigment, 8×8, 2022.

(Erick Cortes)

“You have the mountains. You could drive not too far and be in the desert, or you can be up in the mountains in the snow. Or be on the beaches,” says Hudson. “Yet you still have all this concrete around you and more buildings.” In 2018, Hudson’s work was on display at the California African American Museum as part of the exhibition “Charting the Terrain: Eric Mack and Pamela Smith Hudson,” which focused on how both artists captured the topography of the West Coast.

Hudson’s lens is both local and global, and she says audiences often describe her work as both macro- and microscopic. Whether thinking about increasing homelessness or the effects of climate change on the natural environment, Hudson uses her art to document her connections to the city, and to the land. “Empty Space” showcases her attention to the clash between greenery and concrete, between outer space and the sprawl of the city.

“I want people to look into these small works and see a lot of things going on,” says Hudson. “I think it’s our place and existence. We have a little, small part in this huge, huge universe.”

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.