Looking back at ‘American Prometheus’, the book that inspired Christopher Nolan’s ‘Oppenheimer’

Cillian Murphy as J. Robert Oppenheimer in the newly-released Christopher Nolan film.

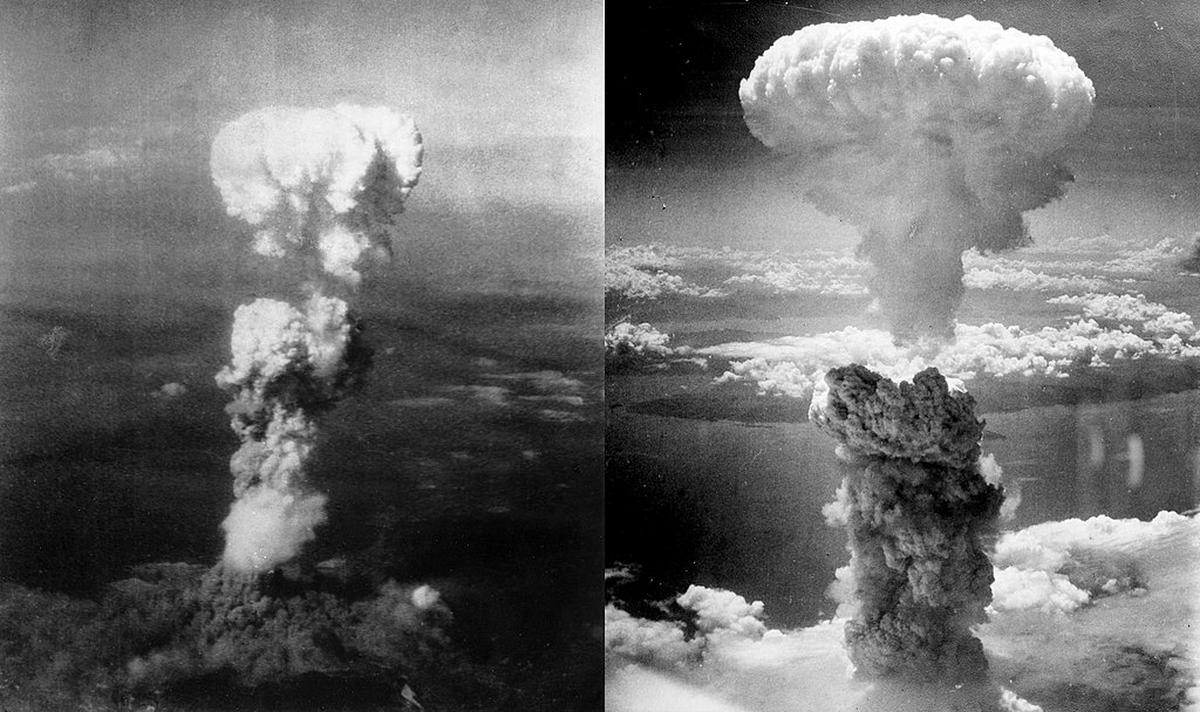

On August 6, 1945, at 15 minutes past 8 a.m., an atomic bomb flashed over Hiroshima, Japan, killing over 100,000 people. Six survivors wondered “why they lived when so many others died”, wrote John Hersey, an American journalist, in The New Yorker (1946).

On August 7, 1945, Japanese radio had broadcast an announcement that a new type of bomb had been used at Hiroshima. It was a time when America was routinely bombing Japanese cities towards the end of World War II. But Hiroshima, and then Nagasaki, were obliterated by the atomic bomb, the first time the weapon had been used.

Atomic mushroom clouds over Hiroshima (left) and Nagasaki (right.)

| Photo Credit:

Wiki Commons

It all began with the Manhattan Project, led by J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb”, a brilliant American theoretical physicist who had learned quantum physics in Germany in the 1920s. His family had moved to the U.S., made wealth in business, and he went from New York to Los Alamos in New Mexico to lead a team of scientists to invent “the gadget”.

‘A Faustian bargain’

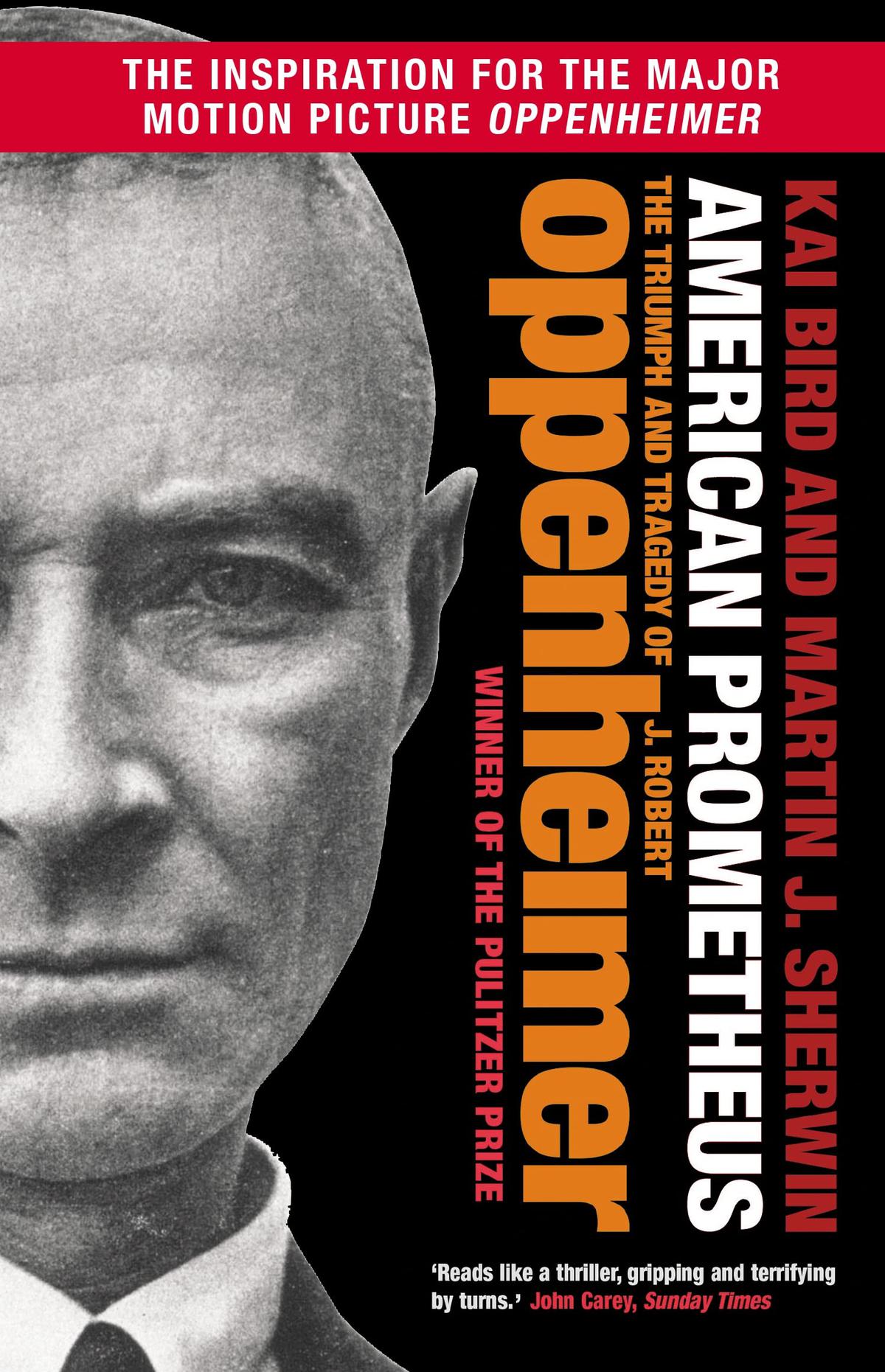

Oppenheimer was “America’s Prometheus”, who headed the effort to “wrest from nature the awesome fire of the sun for his country in the time of war”, write Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin in their gripping Pulitzer-winning biography, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (2005). The book, the primary inspiration for British director Christopher Nolan’s latest film, Oppenheimer, traces the rise and fall of a scientist who was an enigma guided by “his extraordinary intelligence, his parents, his teachers at the Ethical Culture School, and his youthful and professional experiences”.

The insightful biography profiles “Oppie” and his many ambiguities, by talking to his family and colleagues, fellow scientists and brilliant minds. It quotes physicist Freeman Dyson who saw deep and poignant contradictions in Oppenheimer. “He had dedicated his life to science and rational thought,” Dyson observed. Yet, Oppenheimer’s decision to participate in the creation of a genocidal weapon was “a Faustian bargain”. Like Faust, Oppenheimer tried to “renegotiate the bargain” — and was punished for doing so. “Oppenheimer had led the effort to unleash the power of the atom, but when he sought to warn his countrymen of its dangers, to constrain America’s reliance on nuclear weapons, the government questioned his loyalty and put him on trial.”

The first half of the book outlines Oppenheimer’s rise to fame and iconic status in the 1940s; his personal life and tragedies, such as the passing away of his girlfriend; his politics; and the fact that he loved to quote from the Bhagavad Gita, and gift it to his friends. When the bomb was tested for the first time and the mushroom cloud was sighted, Oppenheimer said this line had come to his mind: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds,” which scholars have said should read, “I am time… the source of destruction of all the worlds.”

Tide of anti-communist rising

Emily Blunt as Kitty Oppenheimer and Cillian Murphy as Oppenheimer in a still from the 2023 Christopher Nolan film.

The second part chronicles his downfall, quickened by the tide of anti-communism rising in post-war America. “His post-war resistance to the Air Force’s plans for massive strategic bombing with nuclear weapons — plans he called genocidal — had angered many powerful Washington insiders.” And for this, he had to endure unimaginable agony and humiliation in 1954. He died in his sleep when he was 62 years old, and his wife Kitty confided in a friend how his passing was pitiful. “He turned into a child first, then an infant. He made noises. I couldn’t go into the room.”

It’s impossible to read American Prometheus and not think of one cold fact: that the nuclear path could have been avoided for military purposes. The war was already ending. Japan had sent feelers that it was willing to surrender. The compelling reason behind the nuclear race was no longer an issue. Germany had not come out with an atomic bomb despite whispers to the contrary. Today, the nuclear Damocles’ sword hangs over every powerful and not-so-powerful country.

In 2017, Daniel Ellsberg of the Pentagon Papers fame wrote in his devastating book, The Doomsday Machine, that senior American army commanders were discussing in the 1960s how many people would die if, in the event of war, 40 megatons of N-bombs were dropped on Moscow: the “curve of deaths” was estimated at 100 million with more than half the population of the Soviet Union killed from radioactive fallout alone.

The world has not learnt its lessons, as Oppenheimer had hoped.

The writer looks back at one classic every month.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.