Literary boomer Ann Beattie refreshes her stories — COVID-19, neo-Nazis and all

On the Shelf

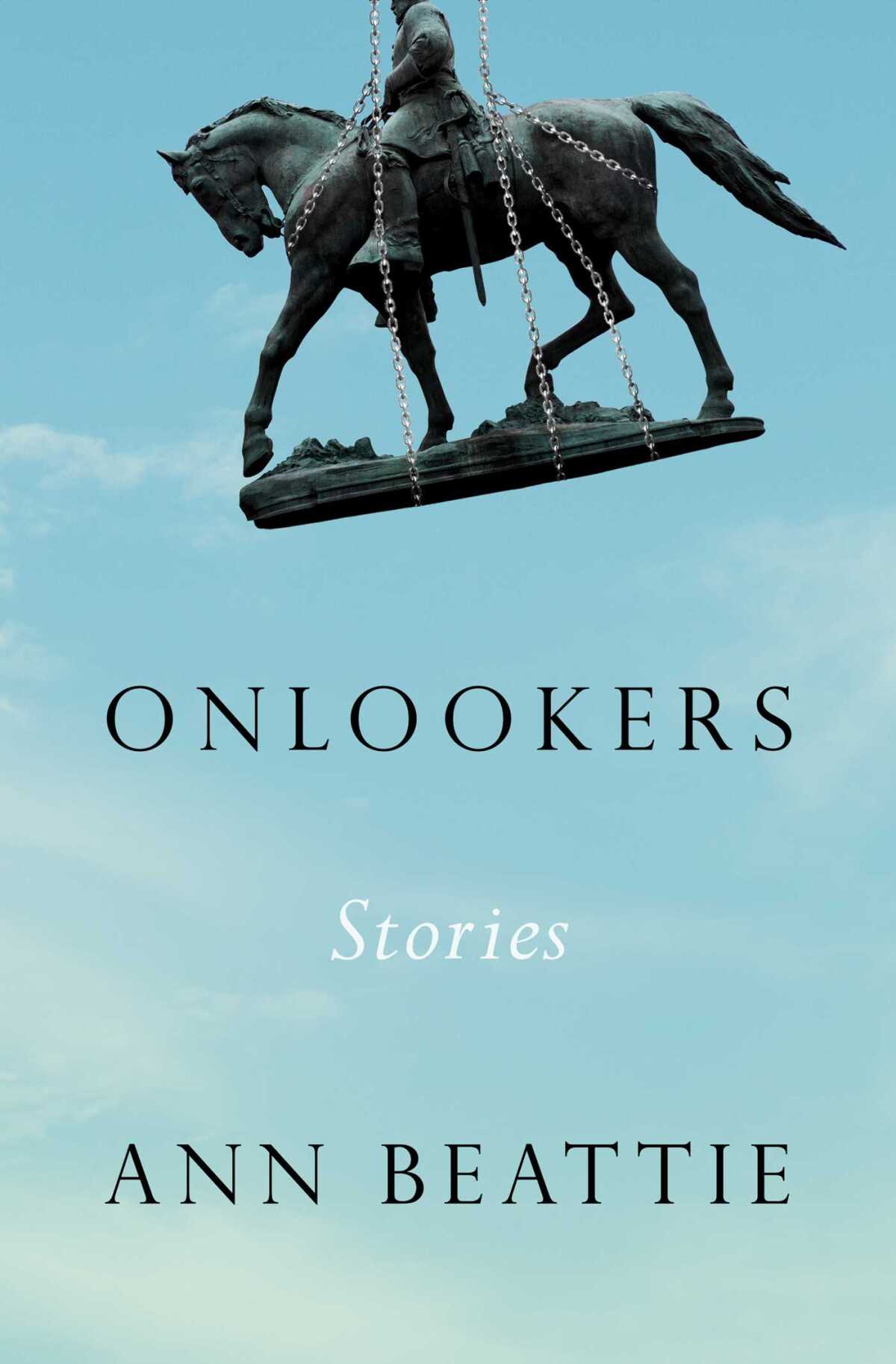

Onlookers: Stories

By Ann Beattie

Scribner: 288 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Consider me a latter-day re-convert to Ann Beattie.

I first read Beattie when I was newly out of college. Her 1976 debut novel, “Chilly Scenes of Winter,” was a touchstone book. Still, for all the acuity with which it and Beattie’s other early efforts (“Falling in Place,” her second novel; the collections “Distortions” and “Secrets and Surprises”) traced the drift of their post-1960s characters, the vision came to feel a little thin. That changed for me with the 2010 novella “Walks With Men,” which reframed that elusiveness, that opacity, by widening the authorial point of view.

“What a strange world it had turned into,” a character thinks in Beattie’s new book, “Onlookers,” which gathers six long linked stories set in contemporary Charlottesville, Va., a city facing a pair of reckonings: COVID-19 and the aftermath of the Unite the Right rally in 2017.

All of us remember what took place: the Nazi flags and tiki torches, the “You will not replace us” chants, the killing of Heather Heyer by a white supremacist. Beattie, however, is less concerned with reenactment than effect, and rightly so; fiction, even when it addresses a particular time and place, is not about history but nuance. It is a mechanism of emotional truth. With “Onlookers,” that makes for a vivid circling as Beattie introduces and re-introduces characters moving in a kaleidoscope of narrative — from the periphery to the center and back again.

The opening story, “Pegasus,” establishes the dynamic: A woman named Ginny, after her fiancé decamps to Japan for an acting gig, moves in with his father, Robbie, “a lovely man, retired, a doctor,” so neither has to ride out the pandemic alone. It’s April 2021, and vaccines have just become available, which makes this a suspended moment in all sorts of ways.

First, there’s that fiancé, Darcy — “(yes, as in Mr. Darcy),” Beattie tells us. (Her parentheticals offer a vivid meta-commentary throughout.) Then there is the doctor’s dead wife, who may or may not keep calling, and his memory, which is suspect. Most of all, there’s Ginny and her feelings for the old man, on whom she’s come to depend. “In spite of his age,” Beattie writes, “in some ways she felt closer to him than she did to Darcy.”

What’s that I was saying about nuance? In Ginny’s reflections, Beattie’s intentions begin to announce themselves. The house is large and well-stocked; no one has to leave to go to work. There is a dog — the delightful Blanche, perhaps my favorite canine character in recent memory — and plenty of outdoor space. That this is fraught goes without saying; “however privileged she and Robbie were,” the author (and character) acknowledges, “how disgusting, in some people’s eyes: Robbie would be the man who’d stayed far away from Lee Park during the Unite the Right rally; he belonged to the country club; there was a cleaning person.”

This is more than character detail or observation; it is a central tension of the book. “Onlookers” is both a title and a state of being, as again and again, Beattie introduces people living at a distance, whether because of COVID-19 or their own independence, which takes many forms. In “The Bubble,” Stacey, the head nurse at an assisted living facility, revisits the area where the rally exploded into violence: “Meanwhile, a rainbow flag flew from the building on the corner, and here she was, driving through the town about which it had been said — more with envy than as a put-down — that it existed in a bubble. But in Lee Park, that bubble had popped — as had her own protective bubble.”

“Nearby,” on the other hand, reflects on the events from a different vantage point, a penthouse apartment overlooking the site. “She could look down on everything,” Beattie notes of Rochelle, the story’s protagonist, “like Dr. T.J. Eckleburg in ‘The Great Gatsby.’” The reference is one it is assumed we’ll understand. Rochelle, after all, is a teacher, filling in at the university for a “famous visiting writer” who has bailed on his responsibilities — privilege in another form.

Beattie does not mean to judge, or not exactly. What she is seeking, rather, is a more expansive empathy. For Stacey, that means looking after the young people who work with her, including George, the damaged son of a friend from church. Rochelle finds herself similarly enmeshed with a student for whom she buys a pair of tires.

Such generational interplay recalls Ginny and Robbie, as well as another character, Monica — who anchors two stories — and her nephew, Jonah. All these people are doing their best to deal with circumstances that are beyond them; all are taking responsibility as they can. That it is not enough, that it can never be enough, is the challenge. “Should they be having this feast,” Rochelle wonders of a takeout dinner, “… when everything that had created the opportunity for it had been discredited, when they were only ascendant because they hadn’t yet died out?”

That’s a question with no answer, the kind only fiction can explore.

Throughout “Onlookers,” Beattie does not shy away from politics; she has nothing good to say about the former president, who haunts these pages like a ghoul. Still, it’s less debate or diatribe that interests her than narrative, which cannot be so definitively resolved.

“It was going to be one of those days,” she observes in “Monica, Headed Home,” “when she’d have to will herself to function.” Beattie may as well be writing about us all. What else can we do in a world where “everybody had their own crazy story”? There is no other option, “Onlookers” insists, except to carry on.

Ulin is a former book editor and book critic of The Times. His novel “Thirteen Question Method” will be published in October.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.