Lex in depth — remittance fintechs herald a payments revolution

For the past few years, Pedro Coelho has been periodically sending £400-£500 at a time home to Portugal. “My grandparents needed surgery so I got together with family to fund it,” he says of one payment. The entrepreneur, who lives in London, is among 170m expatriate workers around the world. Their cash pulses through the veins of the financial system, reinforcing family ties and nurturing weaker economies.

When he first started sending remittances, Coelho, 25, initially used banks. “There was no alternative,” he says. “They charged a steep fee and a big exchange rate.” He now uses a money transfer service operated by Revolut. The upstart digital bank, valued at $33bn in a recent funding round, allows customers one free transfer per month. Coelho pays a subscription for some other services.

Fintech start-ups are finally getting traction in their mission to disrupt banking. Remittances — defined as smaller cross-border payments between individuals — have been an excellent entry point to financial services for many of them. The steep charges of banks and traditional money agents have encouraged tech-conscious customers to shop around. Convoluted legacy systems are ripe for disruption by app-based services.

Specialised businesses are mounting a broader land grab in payments. The industry transfers an estimated $18tn across borders every year. The landscape is highly fragmented, littered with legacy businesses and their systems. That creates an opportunity for well-financed acquirers to snap up rivals. By serving bigger client bases with better technology, they can reduce costs while maintaining profitability.

“It is all about scale”, says Ron Kalifa, a UK government adviser on fintech and chair of Network International, a payments group focused on the Middle East. The urge to consolidate triggered more than $54bn in cross-border takeovers in 2020 and 2021, according to Dealogic.

Investment capital is flooding into an industry once dismissed as “plumbing” by bankers. “In the past, people would drift away from you at a party if you said you worked in remittances,” says Michael Kent, founder and executive chair of Azimo, a payments business specialising in developing countries. “These days you tell them you’re in fintech and they get excited.”

The remittance revolution is challenging traditional money agents such as Western Union and MoneyGram, once seen as operating rock-solid franchises. There is a threat to banks as well. Digitally based rivals aim to unbundle the services they bring together, of which money transfers are just one example.

At either end of complex webs of financial relationships are expatriate earners such as Coelho. Families back home can look forward to bigger remittances from expatriate earners like him because technology and competition are reducing costs. This is before the much ballyhooed — and for the moment entirely theoretical — possibility that blockchain-based digital currencies will create a frictionless, fully automated world payments system.

The trick for investors will be distinguishing between businesses building valuable territories and those staking claims to worthless badlands.

Kalifa’s comment on scale applies here, just as it would in ecommerce, social networks and streaming. The more customer demand and data you can aggregate, the more impregnable your position will become. But there is peril for would-be consolidators too. In every business land grab, some contenders always overpay for acquisitions that bring few benefits and brake rather than accelerate their progress. Here it is vendors, including founders of fintech start-ups, that stand to gain the most.

Wise vs world

Like any comic book hero, a would-be consumer champion needs a good back-story. The tale told and retold by Kristo Kaarmann is of self-help that turned into Wise, the money transfer business he co-founded.

Kaarmann, an Estonian, was working in London for Deloitte. Taavet Hinrikus, a UK-based friend, was toiling in Estonia as a financial consultant. “I was sending money to Estonia and he was sending money to the UK. We were both losing thousands in hidden foreign exchange mark-ups,” Kaarmann says. “So we set out to do transfers without banks. Every month we looked up the exchange rate. I topped up Taavet’s UK bank account and he topped up my Estonian account by the equivalent amount.”

The beauty of the arrangement was that no money needed to cross borders. The contrast was with correspondent banking, the traditional, friction-laden route for retail payments to cross borders. Here, a remittance sent by a customer of a purely domestic bank may pass through three other institutions before it reaches a recipient overseas: a process described as “nonsensical” for customers by Leon Isaacs, a payments consultant.

For incumbents, it is a decent earner. Each bank in the chain may be able to take a fee and a foreign exchange mark-up.

Wise claims its money transfers are up to eight times cheaper than UK high-street banks. A transfer of £1,000 costs just £3.75. Wise also aims to be faster, with four out of five payments arriving in a day or less. Remittances via the correspondent banking network can take two to five days, with each link in the chain settling on consecutive days.

Kaarmann and Hinrikus originally hoped their “netting” — reciprocal payments in matched countries — would be the bedrock of their business. In practice, it constituted only around 15 per cent of $74bn in transfers via Wise last year, because flows between two countries are typically lopsided. Chief technology officer Harsh Sinha says the efficiencies that make Wise price competitive come largely from bulk dealing in currencies and connecting domestic payments systems in each country where it operates.

For investors, Wise’s equity capitalisation is more eye-catching than its financial plumbing. The business recently joined the UK stock market via a direct listing that valued it at £9.3bn ($12.6bn). That means the start-up is worth around one-third more than Western Union. The latter, thanks to its 170-year history and agents in 200 countries, is the world’s best-known remittance specialist.

New York-listed Western Union has an enterprise value twice estimated revenues for next year and eight times earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation. The equivalents for Wise are 18 times sales and 75 times ebitda.

Some people would demur at the comparison. These are quite different businesses. But that is the point. Wise has characteristics investors prize. It is fast-growing, purely digital and appeals to young, early adopters in white-collar occupations. Western Union is pushing into online payments in a bid to modernise. But its other distinguishing features deter most investors. Only one quarter of transactions were initiated electronically last year. The vast bulk of transfers for a loyal but typically lower-waged customer base of migrant workers were completed in cash.

It is easy for payment start-ups to attract capital, harder to outpace competition from their own kind. For Wise, Revolut is a case in point — Coelho is among customers who have switched from the former to the latter.

Lex views Wise as an investment that will either fly or flop, disrupting a staid industry or never transcending its niche status. “It’s not quite a case of Amazon versus Barnes & Noble,” says Kent, pondering the contrast between Western Union and groups like Wise, “but some of the same factors are at play.”

Remittances for development

For the World Bank, tech disruption of global payments is something to celebrate. The development institution is sometimes accused of pushing for economic efficiency at the expense of individual welfare. The two mesh harmoniously in falling remittance prices.

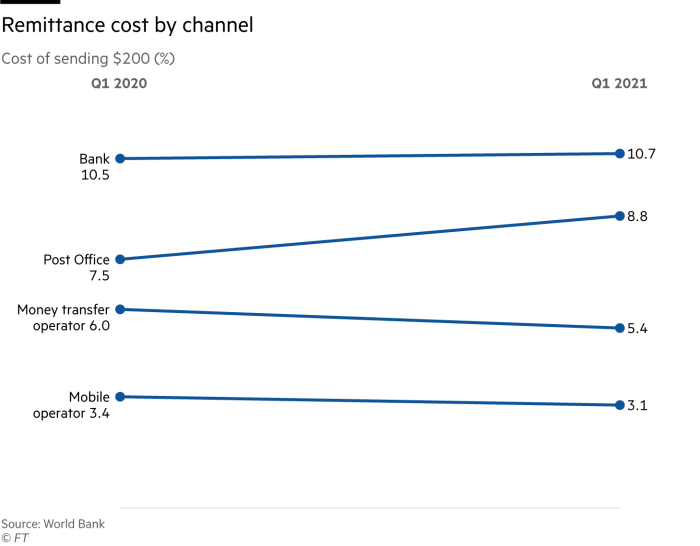

Figures compiled by the bank show the global average charge has dropped from around 9 per cent in 2011 to 6.4 per cent today for a cross-border transfer of $200. That is still high compared with the cheap or free services offered by start-ups such as Wise and Revolut in the developed world.

Charges below 5 per cent in five years, a target adopted by the G8 in 2009, has been achieved when measured as an average weighted for the value of transactions. This has fallen to 4.54 per cent. A 2030 target of 3 per cent or below is “within reach”, according to Mayada Elzoghbi, managing director of the Center for Financial Inclusion, a charity based in Washington DC.

Correspondent banks, however, are dragging the anchor. On average, they charge almost 11 per cent for a $200 switch. Money transfer operators such as Western Union are around 50 per cent cheaper. Mobile phone-based services typically cost two-thirds less than the banks.

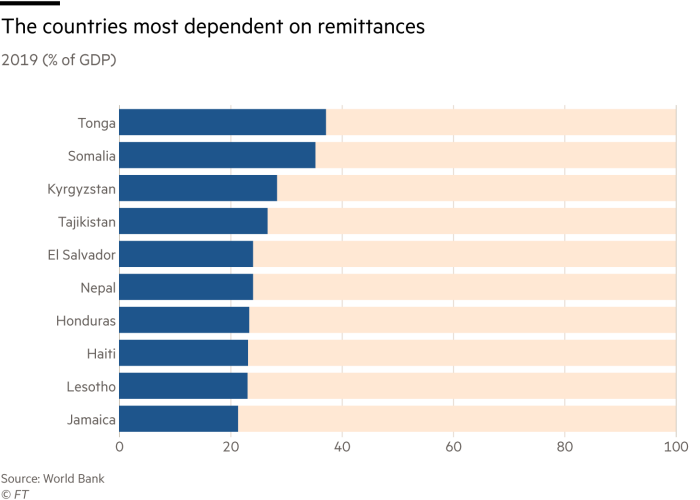

Lower costs benefit poor countries by increasing the sums recipients there can invest in healthcare and education. Remittances are a lifeline for the developing world. They were worth $548bn in 2019, slightly more than the entirety of foreign direct investment. Development spending, most of it from governments in wealthy countries, was a relatively puny $166bn. Remittances are equivalent to more than a third of gross domestic product in Somalia, Lebanon and Tonga.

The projected 1.54 per cent drop in the weighted average cost of transfers is equivalent to $9bn in extra yearly income for developing nations.

The World Bank predicted remittances would fall sharply in the pandemic, as transport routes seized up and migrant workers were short of work. Instead, payments fell only 1.6 per cent. Avril Sharp, a caseworker at Kalayaan, a UK charity that helps lower-paid female migrant workers, says: “Their focus is always on remitting money home. They will sacrifice their own welfare to do so.”

While acknowledging the dedication of migrants, Elzoghbi also points to structural factors. Lockdowns pushed cash on to formal, regulated platforms when much of it would normally cross borders in the pockets and luggage of travellers. Governments loosened anti-money laundering controls, making it easier for workers to register digital accounts.

That has played out against a broader trend of tighter restrictions on flows from the developed world. A clampdown on dirty money — including drugs trade proceeds and terror funding — was needed. An unintended consequence was to encourage “de-risking” by multinational banks such as HSBC. The lender paid more than $1.9bn to US authorities in 2012 for permitting money laundering. Pulling out of small, chaotic and marginally profitable territories makes sense as a business strategy. But it can increase the cost and lower the availability of remittances crucial to the welfare of some inhabitants.

Technology can at least reduce financial exclusion in poor but relatively populous countries where mobile phone penetration is high. The classic example is M-Pesa, the app-based mobile money service pioneered by Kenya-based telecoms operator Safaricom which has attracted 46m active users in seven countries.

“Mobile transfer services have significantly lowered the cost of money to the unbanked, and it has done so at scale,” says Mahesh Uttamchandani, practice manager for financial inclusion at the World Bank. “And there is further disruption on the way.”

Tiny increments, vast totals

The same applies to the broader global payments industry, of which remittances are just a subset. Cross border payments amount to $18tn annually, around $2tn of which falls into the “personal” bucket, according to estimates from Edgar, Dunn & Co, a consultancy.

The World Bank’s Uttamchandani sees similarities between global payments and the airlines industry when the first low-cost carriers emerged: “Back then, scrappy new operators picked off valuable airline routes. Many fintechs are picking off valuable payment corridors without offering a full global service.”

The implication is that banks and traditional money agents will always struggle to compete, constrained by broad customer service promises supported by large physical distribution networks.

Payments is a business where banks — with the exception of a few large players — will increasingly depend on specialist service providers and network companies to move customers’ money around. Lenders will remain at the heart of the system, taking deposits and making advances on credit. Most of the new entrants do not want to shoulder the regulatory capital costs that come with this. But the reach of the banks will be reduced.

That thesis has triggered a race among payment businesses to bulk up in capital-light payments.

Worldpay is the most striking — and for banks, discomforting — example of a missed opportunity in payments. Cash-strapped Royal Bank of Scotland sold the processing business to private equity at an enterprise value of some £2bn in 2010. After £1.5bn of investment and six bolt-on acquisitions, Advent and Bain floated Worldpay at a valuation of £6bn in 2015.

Two years later, US rival Vantiv, bought Worldpay for a couple of billion more. Another American payments group, Fidelity National Information Services, snapped up the combined business at a $43bn valuation in 2019.

The expanded FIS, spanning payment processing for merchants, banks and capital markets, is now valued at $92bn on the New York Stock Exchange. It handles 80bn transactions worth $10tn annually, generating ebitda of around $4bn.

Its vital statistics — equivalent to 5 cents of earnings per transaction — shows that taking a small turn on every deal adds up to a lot when you have plenty of deals.

Rival US payments business Square has a higher profile thanks to tech billionaire founder Jack Dorsey. It recently struck a deal to acquire Australia-based buy-now-pay-later specialist Afterpay for $29bn in stock. It is still dwarfed by non-bank incumbents in payments. These are led by Visa, which runs the world’s largest cards-based network, and is capitalised at more than $500bn. Online payments specialist PayPal is another, with a market worth of $350bn.

Incomers are poorly placed to challenge these giants. But there is plenty of territory they can still wrest from banks, as changes in the remittances sector illustrates. “Ultimately you will have big payments groups controlling whole regions,” says Kent.

Elzoghbi at the Center for Financial Inclusion sees “big risks of monopolistic behaviour down the line”. But in online payments, the network effects — where customers become increasingly captive — may be weaker than in other areas of tech. When switching is easy and charges are transparent, competition may simply compress prices, as it has in mobile telephony.

That moment has already arrived in parts of the remittance industry. Tamara Ristic, 28, a City of London solicitor, used to pay £15 every time she sent money home to Cyprus via banks to repay a loan covering study costs. “I never understood why it cost so much,” she says. Now she uses the free service offered by Revolut, a business that for the moment is running at a loss. Such thrifty and unlucrative customer habits may prove hard for payments companies to break as they build up their disruptive networks.

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.