Kids want to know: ‘Will It Be Okay?’ — this book answers that question

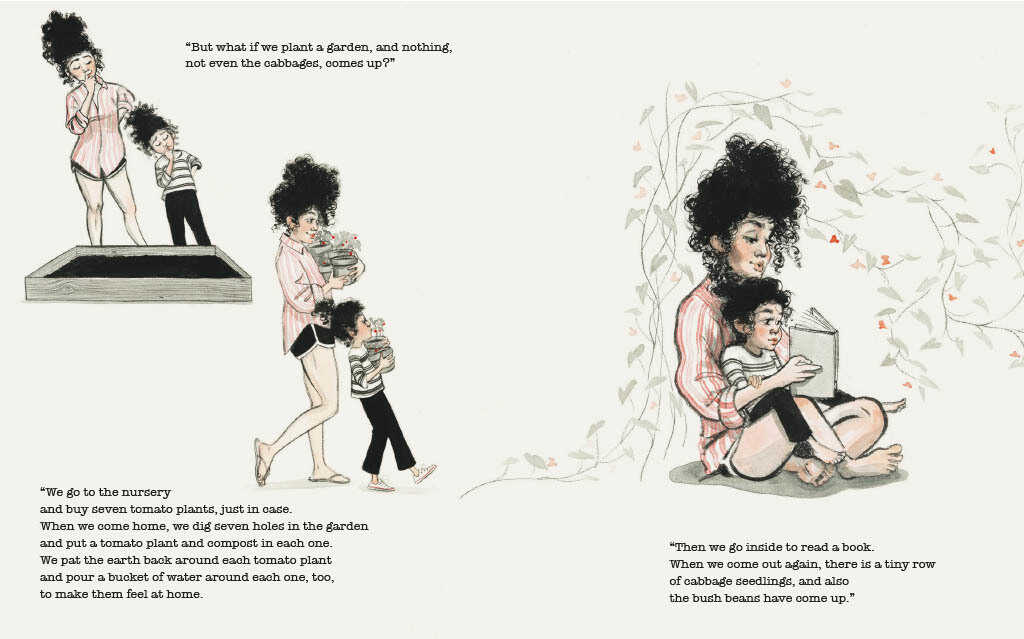

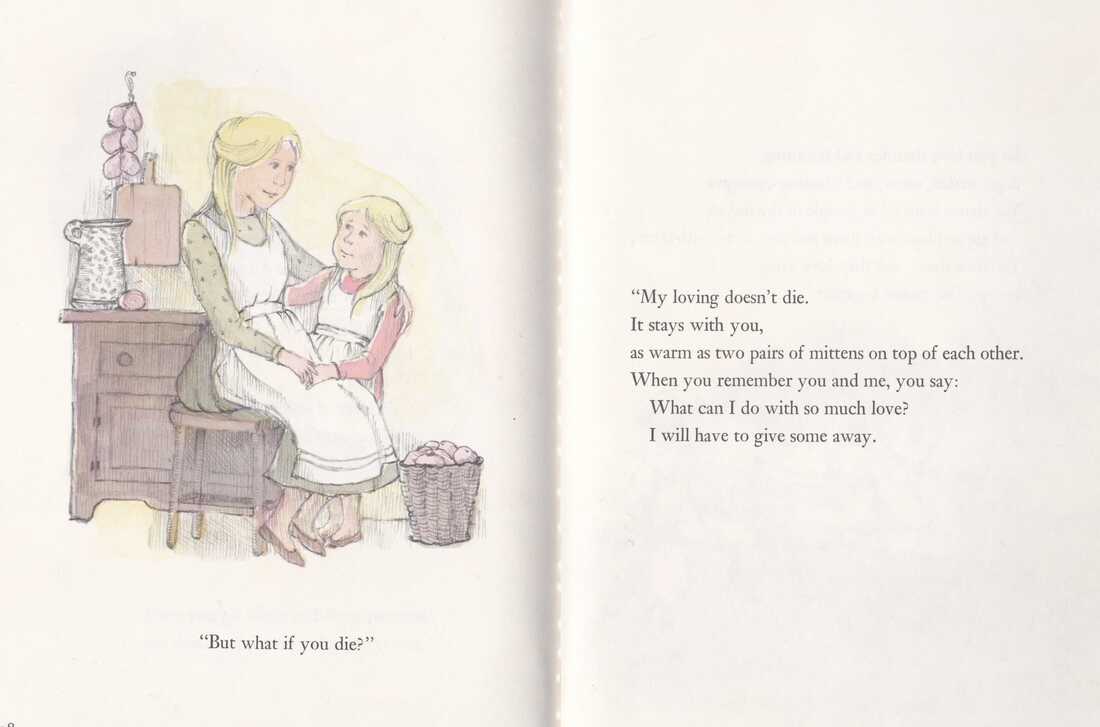

“Will it be okay?” “Yes, it will.” At left, a page from the 1977 edition of Crescent Dragonwagon’s Will it Be Okay? illustrated by Ben Shecter, and, at right, the same page from the 2022 edition, illustrated by Jessica Love.

Ben Shecter / HarperCollins / Jessica Love/Cameron + Company

hide caption

toggle caption

Ben Shecter / HarperCollins / Jessica Love/Cameron + Company

There are a lot of “what ifs” when you’re a kid: “What if a bee stings me?” “What if I forget my lines in the school play?” “What if people don’t like me?”

At the heart of all these questions is a desire to know: “Will it be okay?”

That’s the title of a 1977 book written by Crescent Dragonwagon — a story told entirely in dialogue between a mother and her child.

“I’ve always had a healthy respect for the feelings that children have,” says Dragonwagon, “so in the story the little girl asks the questions and her mother answers them in a way that is not condescending. It’s funny. Sometimes it has some wisdom in it.”

Dragonwagon was in her mid-20s when she first published Will It Be Okay?— a time when she says she was much more the child in the story than the adult. Now 70, Crescent Dragonwagon has written more than two dozen children’s books, as well as novels, cookbooks and poetry.

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit in 2020, Dragonwagon says she felt like she needed something to do. She and her husband started reading children’s books out loud every night.

“The first book that I chose to read was Will It Be Okay? because it’s my most reassuring book,” Dragonwagon says.

Jessica Love/Cameron + Company

But the book had been out of print since 1991. She decided to give it a new life. She re-wrote parts of it (taking out, for example, a line about a “Thanksgiving play” and swapping in “school play” instead). And she made one other big change: all new illustrations.

The 1977 illustrations by artist Ben Shecter were soft and sentimental. Dragonwagon says she liked the way he captured the fear of the little girl — but felt the illustrations didn’t really show her strength.

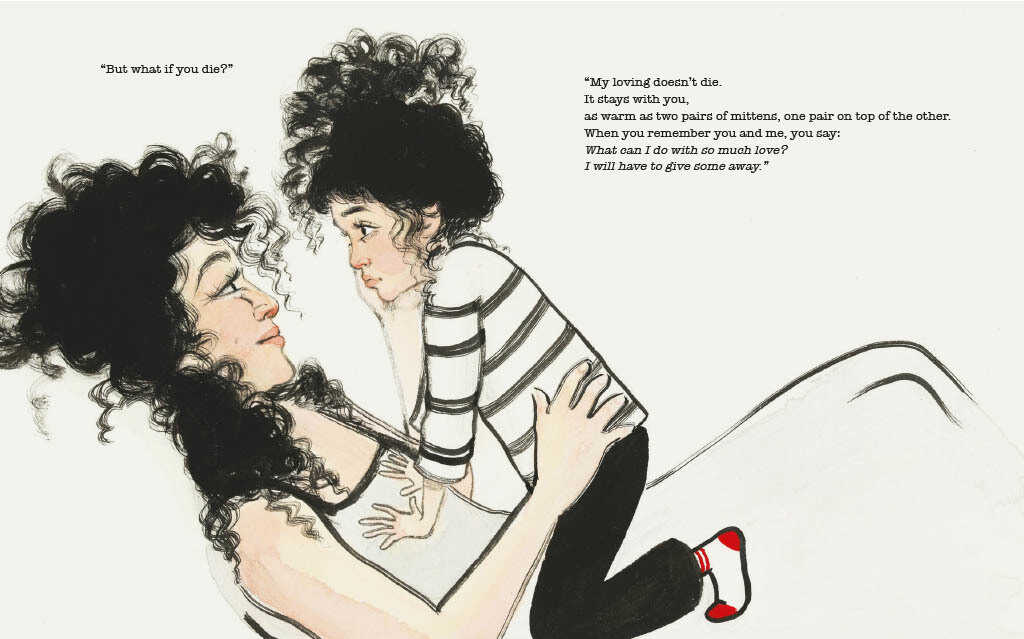

For the new book, Dragonwagon turned to Jessica Love, the critically acclaimed author and illustrator of Julián Is a Mermaid.

“I made it three lines, maybe four, before I felt absolutely certain that if someone took this job from me, I would have to hunt them down and get it back,” says Love.

Love says she intentionally did not look at the earlier version of the book — she knew she wanted her illustrations to have the feeling of a print: punchy and graphic. She did the illustrations by hand with thick lines of Sumi ink.

“I kind of dry it out so that the line doesn’t look wet,” she says. “It looks a little draggier … almost like a pencil.”

She limited herself to three colors: black, red, and yellow — which she mixed together to create a variety of pinks and peaches.

“I wanted the artwork to have a similar structure to it, and restraint to it,” says Love. “In the way that the text is limited to these questions and then answers.”

The mother and her daughter both have big, curly black hair, pink cheeks and expressive eyes. They dance and spin across the pages — they look like best friends.

“When I saw Jessica’s pictures, I just thought ‘Wow!’ ” says Dragonwagon. “It’s just so delightful, goofy, and powerful. … She exactly gets the emotions across.” The child’s absolute horror when she forgets her lines in the play. Her feeling of triumph when she makes up new ones.

Will It Be Okay? written by Crescent Dragonwagon and illustrated by Jessica Love.

Jessica Love/Cameron + Company

hide caption

toggle caption

Jessica Love/Cameron + Company

Though Dragonwagon and Love did not collaborate directly on this children’s book, Dragonwagon did look Love up online.

“When I first started in children’s books, they attempted very vigorously to keep the artist and the writer separate,” she explains. “However, in the age of the internet it’s not so easy to keep people apart.”

Mostly they just exchanged a few emails about how thrilled they each were to be working with each other. They didn’t speak face-to-face until this interview, but say it felt like working with a kindred spirit.

“It’s that thing that happens when you read someone’s writing that speaks just like it’s being whispered into your ear,” says Jessica Love. She especially connected, she says, with the way the mother speaks to the child.

“It’s the quintessence of the way I longed to be spoken to as a child,” she says. “You can feel it when you’re talking to a little kid and they sense that they’re being taken seriously.”

“What if someone doesn’t like me?” the child asks in the book.

“You feel lonely and sad,” the mom answers. “You walk and walk until you come to a small pond. You kneel in the grass by the edge of this pond and you see something move. You put out your hand and a tiny frog no bigger than your thumbnail hops into it. Very carefully you lift your hand up to your ear and the frog whispers, ‘Other people like you, other people love you.’ “

One of the things that Love says she found the most helpful in Dragonwagon’s writing was the practical advice: get up, take a walk, move your body, rub an onion back and forth on your bee sting. “It gives you a scaffolding, a framework, to harness the galloping horse that is your frightened child brain,” she says.

Ben Shecter / HarperCollins

Ben Shecter / HarperCollins

Because, of course, the child in the book is working herself up to asking the biggest, scariest question of them all: “But what if you die?”

Dragonwagon says she doesn’t want to hide the truth from kids — life is full of upsetting things! Instead, she hopes this book helps kids, and adults, get through it.

“My feeling is that feelings want to be felt,” she says.

And so the mother answers the child: “My loving doesn’t die. It stays with you, as warm as two pairs of mittens, one pair on top of the other. When you remember you and me, you say: What can I do with so much love? I will have to give some away.”

Dragonwagon says she doesn’t know how she came up with the answer to this question when she was in her 20s. But now, decades later, and after having lost her parents, friends, and two husbands, she is certain that it is true.

“There’s not a day that I don’t think of them,” she says. “But truly their loving doesn’t die.”

“So it will be okay?”

“Yes, my love. It will.”

Jessica Love/Cameron Company

Jessica Love/Cameron Company

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.