Iran’s storytelling tradition spans centuries. A woman in Tehrangeles has revolutionized it

In a lavish West Hollywood banquet hall adorned with the colors of spring, the Iranian epic storyteller Gordafarid strides across the stage like a mythical heroine, dressed in a white embroidered vest, black bell sleeves and white knee-high boots. A silver beaded scarf is arranged like a crown on top of her long, dark hair.

It is Nowruz — the Persian New Year — and the Iranian American Jewish Federation has invited the 46-year-old to perform along with other Iranian female artists — drummers, dancers and singers. The event and fundraiser is a celebration of the country’s cultural heritage and a tribute to the female artists back home who are forbidden by the government to sing, dance or play music in public.

The audience falls quiet as Gordafarid’s commanding, raspy alto fills the room with melodic Persian. With a mixture of prose, poetry, stomping and pantomime, she captivates the audience as she has others for more than 25 years, with tales from the Shahnameh — the national epic poem of Iran completed by the poet Ferdowsi in the year 1010.

For centuries, skilled Iranian storytellers known as Naqqals have transfixed audiences in traditional coffeehouses with stories from the 50,000-verse Shahnameh, but historically it was an art performed by men, for men. Gordafarid, whose life story is an epic in itself, is the first known female Naqqal to have learned the craft the traditional way, from the Morsheds, or Naqqali masters.

Gordafarid’s fearlessness and determination have made her a beacon of inspiration to Iranian audiences around the world at a time when female-led protests have erupted across her homeland after the death in custody last year of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, arrested by Iran’s morality police for allegedly not covering her hair properly.

“When you hear a young lady like Gordafarid, who is so devoted to preserving the heritage that the Islamic Republic has tried very hard to annihilate over the years, it is reminiscent of what we’re seeing from the youngsters on the streets of Iran,” said Zohreh Mizrahi, an immigration lawyer in L.A. who served as emcee for the Nowruz event. “People feel like there is hope, and we see that hope in her.”

Los Angeles resident Gordafarid is the first known woman to have mastered the ancient Iranian storytelling art of Naqqali.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Gordafarid moved to Los Angeles from Tehran in 2010, after the government banned her from speaking in public. People often cry when they see her perform.

“I think I touch their heart with my energy because I am onstage with all of myself, all of my soul, in every word,” she said.

The night of the Nowruz celebration she explained the origins of the festival as a tribute to Jamshid, whom the Shanameh describes as the greatest Iranian king. Then she told the story of another ancient king who stumbled across a beautiful palace while searching for his mythical horse, Rakhsh. In rhyming couplets, she described the wonders of the castle, speaking faster and faster until the audience stood on its feet, applauding with awe.

“It’s incredible, just incredible,” said Saleh Mishael of West Hollywood, who was wearing a deep V-neck top and black leather skirt. “The way she was saying all the adjectives and that she memorized it all, it was incredible.”

Column One

A showcase for compelling storytelling from the Los Angeles Times.

After a buffet dinner, Gordafarid returned to the stage to tell the story of her namesake — the female warrior Gordafarid, who rode into battle to defend her country when the men were too afraid to fight.

Even a non-Persian speaker could make out the key elements of the tale — Gordafarid donning a helmet to obscure her femininity, riding her horse fearlessly into battle, sending her arrows flying through the wind. When her attacker finally removes her helmet with a spear, he is stunned to discover his adversary is a beautiful young woman with long, flowing hair.

“Like Joan of Arc in Western culture, Gordafarid epitomizes the character and strength of women from ancient times,” Mizrahi said. “Any time you deal with a woman who is very strong and very determined, and not afraid of anything, we call her a Gordafarid.”

A few weeks after the performance, the modern-day Gordafarid (she officially changed her name to Gord Afarid after receiving U.S. citizenship) pushed a basket of flatbread to the side at a Persian restaurant near her home in Encino and apologized. “It’s not fresh,” she said. “I don’t know why.”

Then she opened Google Translate on a silver laptop to help her more accurately express herself in English as she prepared to tell her own story.

It begins in the city of Ahvaz in the southwest of Iran, where she grew up the daughter of a farmer and a homemaker, the eldest of five children. The 1979 Islamic Revolution began two years after she was born, and for the next nine years, Ahvaz, which sits near the Iraqi border, was engulfed in war. On her computer she calls up photos of tanks in city streets, men with large guns, piles of rubble where buildings once stood.

“I think I touch their heart with my energy because I am onstage with all of myself, all of my soul, in every word,” Gordafarid says.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

“I remember all of this,” she said, scrolling through the images. “A lot of rockets, a lot of people died; some of my family died. That’s why I say, my city was so beautiful, but after the war. … I remember all these things.”

Her family members, most of whom still live in Ahvaz, are Muslim, but in her teens she decided she didn’t like religion. When her father tried to force her to marry at 15, she refused. She rebelled at school, but always loved theater and tales of adventure.

Many Iranians grow up hearing the stories of the Shahnameh, known in English as the Book of Kings, from their parents. But Gordafarid knew only the few tales she learned at school. It wasn’t until 1998, when she was a university student in Tehran, that she saw her first Naqqali performance. She was drawn to it instantly.

“In its own way, it is a one-person theater,” she said, stirring a pat of butter into her white- and saffron-colored Persian rice. “A Naqqal edits his own scripts, directs the performance himself, and creates various characters. He does not hesitate to imitate the lion’s roar, the horse’s neigh, and the roar of the dragon.”

She asked the performer — a student himself — to teach her Naqqali, and after just a few lessons she was invited to perform at a private salon for 300 people. A friend introduced her, and let the spectators know they were about to witness something historic: The first woman known to perform Naqqali before an audience.

Gordafarid remembers stepping quickly onto the stage and beginning with a traditional song, from which she took courage. Then she recited from the Shahnameh for the next half-hour.

Nowruz celebrants applaud Gordafarid at her performance in West Hollywood.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

“It was my first time in front of people, and they were shocked because I memorized 30 minutes of Shahnameh,” she said. “They clapped for me, and then they got my phone number.”

She met her mentor, the late Naqqali master Morshed Torabi, a few months later. She had been invited to give a public Naqqali performance for Nowruz, but because reporters and news cameras were going to be present, this time she felt she needed help.

The men at the theater building where Torabi worked refused to give her his phone number because she is a woman. “They were closed-minded,” Gordafarid said. “They made excuses, like, ‘He doesn’t have a phone.’” Eventually she found his number and called him. “His voice was warm and scratchy,” she said. “A rusty voice.”

She told him she needed a toomar, or traditional Naqqali script, that would be appropriate for Nowruz. He told her she must recite the story of Jamshid and how the festival came about. She asked if she could come meet him, and he agreed.

She traveled across town to the same theater building where she had originally been turned away. They spoke for a few minutes, and then he handed her a few lines written on a piece of paper — a brief outline of what she should say.

“Morshed said, based on this summary of explanations, ‘You write, you edit, you organize your own toomar,’” Gordafarid said. “He was very rough and tough.”

Soon she was following Torabi around the city, silently taking notes on his performances in the all-male spaces where Naqqali is traditionally done. Although he let her know where he would be, he did not offer to teach her. “He was very impatient, so I didn’t ask him any questions,” she said. “I was very patient, and I had a lot of respect for him.”

One day an old man at a traditional coffeehouse asked the Naqqal about the girl in the corner. Torabi thought and thought. “She is my student,” he said at last.

“It was hard for him because it is taboo,” she said. “But he admitted he had never seen so much follow-up, effort and respect from his male students.”

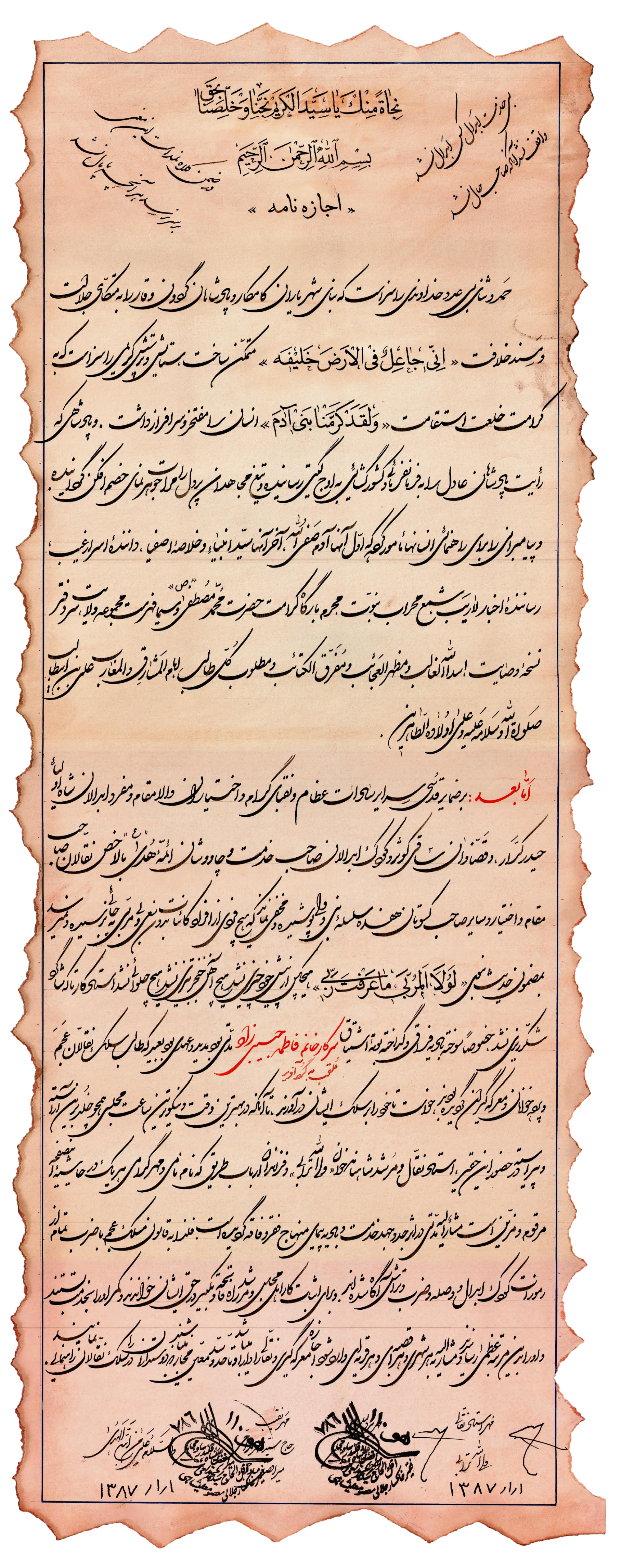

A certificate signed by four famous Naqqals declares Gordafarid the first female Naqqal in history.

(Courtesy of Gordafarid)

Two years later, at the famous City Theater in Tehran, Torabi presented Gordafarid with his sturdy wooden cane — a public acknowledgment that she was not just his student, but his heir.

“Always when I have a goal, I focus on it with all my cells,” she said. “Everything. And maybe I don’t care if it is a taboo or not. Several times I broke taboos, not just this. I fought with my father, the city, school rules, because everywhere was a dictatorship.”

As a scholar and performer of Naqqali, she traveled across Iran to study with other teachers. She spent four hours a day strengthening her voice and taught Naqqali to others. She performed in front of audiences of tens of thousands and received a certificate signed by the top Naqqals in the country declaring her to be the first female Naqqal in Iranian history.

Naqqali was placed on the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage in need of urgent safeguarding in 2011; photos and video of Gordafarid’s performances were included alongside those of other masters.

But around 2009 and 2010 she found it increasingly difficult to find work in Iran. In addition to performing Naqqali, she also worked as a writer, programmer and presenter for television and radio. Along with many other women, she was banned from working in those fields by an increasingly conservative government.

“In that time it was forbidden for a woman to raise her voice in public, and I did, a lot,” she said.

Falling into a depression, she decided to move to Los Angeles, wondering if she would have to take a job at McDonald’s.

Instead, she started getting Naqqali work in L.A., which is home to more than 130,000 Iranians, the largest population outside of Iran. She was invited to perform at museums, universities, for cultural federations. She toured Europe and Canada.

“That was good,” she said, as she cut into the sweet and sticky zoolbia, a crispy fried dough dessert at the Encino restaurant. “I thought maybe they will forget me in history, but no.”

Last year, Gordafarid was commissioned by the Farhang Foundation, a nonprofit devoted to celebrating and promoting Iranian art and culture, to make a video in honor of the Iranian winter solstice holiday, Shab-e Yalda.

In the video, released on YouTube at the end of December, she is dressed in form-fitting black velvet with her signature bell sleeves and a thick belt around her waist. Images appear behind her to illustrate a different tale from the Shahnameh: The story of the malevolent King Zahhak, who falls under the sway of an evil spirit who curses him. The spirit makes two serpents grow out of his shoulders; they must feast each day on the brains of young people.

For some, the story serves as a gruesome metaphor for the Iranian government’s deadly crackdown on the many young people who took to the streets last fall to protest the country’s restrictive clerical rule after Amini’s death. Government agents were responsible for the deaths of at least 44 children during the months-long uprising, with hundreds more detained, according to Amnesty International and other human rights groups.

Gordafarid whispers conspiratorially when she speaks as the flattering evil spirit. When she is Zahhak, her arms turn into two vicious snakes that hiss at the air.

“It’s really a David and Goliath story, and it is very relatable to what is going on in Iran,” said Alireza Ardekani, executive director of the Farhang Foundation. “The great thing about the epic Book of Kings is there’s always a story that can be relatable to anything in life.”

Gordafarid says she can never go back to Iran. “I would love to go, but I’m sure if I go there — straight to jail,” she said.

She misses her home country, but she has made a life for herself in Los Angeles. When she is not performing Naqqali, she works as an occasional instructor for UCLA Extension, where she teaches Persian language, Naqqali and the Shahnameh. Recently, she was hired by Disney as a mythologist to advise writers on a project due out in 2024. And she makes ends meet by working as a medical assistant at an inpatient anorexia clinic.

In the meantime, she is an inspiration to a new generation of female Iranian artists, some of whom are incorporating the art of Naqqali into their own performances.

They may study her work on YouTube rather than at the traditional coffeehouses of Iran, but they, too, are learning the ancient art of Naqqali from a master.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.