India’s 1983 World Cup triumph: The game changer | Cricket News – Times of India

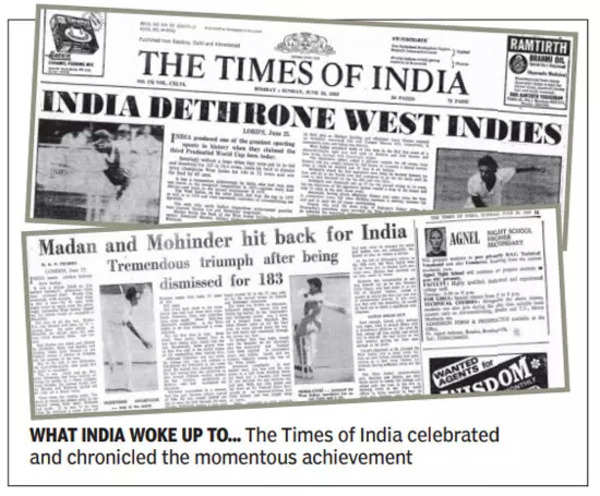

It was a day “when cannon fodder turned cannon”, London’s Sunday Times reported. It was a day when “the World Cup no-hopers stopped the Calypso kings in their tracks,” said Englandgreat Denis Compton in Sunday Express.It was a day when the unthinkable happened. Andcricket in India was never the same again.

The World Cup triumph — the first ever in cricket — came when the country was at the cusp of a technological revolution. In the 1970s, even in the early 1980s, international cricket was primarily about listening. Test matches were physically watched by thousands in packed stadiums in the metros, but radio pleasured millions across the land.

From government offices to bus stops, from cigarette shops to railway stations, running radio commentary was both a personal and a shared collective activity cutting across classes. You could interrupt anyone with the transistor for the latest score. Now change was happening.

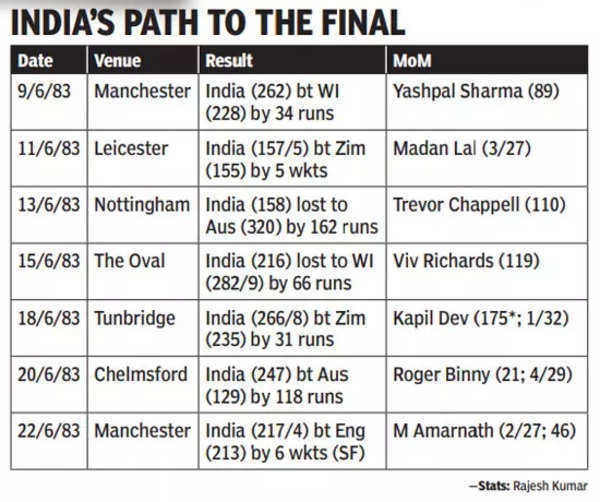

In 1982, Doordarshan started national programming. Colour transmission began the same year. Well-heeled metropolitan India watched the 1982 Delhi Asian Games live on colour TVs. Many more saw Kapil and company produce the improbable at Lord’s, the first cricket World Cup shown on television. Small-towners like me, though, followed the national team’s fortunes — 66:1 was India’s title odds when the championship began — on BBC World Service. I was aware of Berbice and had rejoiced at the team’s Old Trafford triumph.

But a victory in the final against Clive Lloyd’s almighty Windies seemed a dream too fanciful, a prospect as improbable as Uruguay’s win over Brazil in the 1950 football World Cup final. I see-sawed between agony and ecstasy listening to the radio commentary that evening.

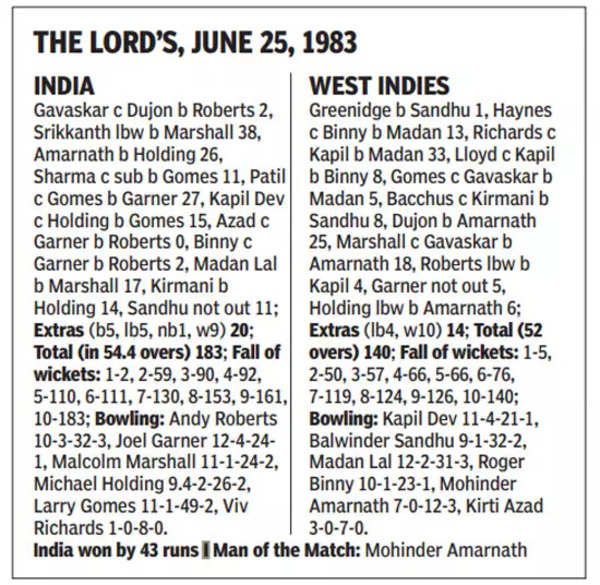

In a few weeks, the video recording of the Lord’s final was available for viewing in masochistic, makeshift auditoriums for a price of Rs 5. I sat among a bunch of hardscrabble men in a smoke-filled room next to a coal depot to watch Srikkanth deposit Andy Roberts to the square-boundary. Wisden described it as ‘a pistol

shot.’

I watched a cocky Vivian Richards produce a T20 cameo in times of 60-over ODIs. I gasped as Kapil Dev ran backwards to take India’s most remembered catch ever. When Amarnath trapped Holding leg before, the room cheered as if we were watching the game live.

Till then, BCCI had largely ignored ODIs. But the cricket public had now been truly seduced by the game’s shortened variety.

“In September 1983, a sort of one-cricket wave swept the country,” wrote Mihir Bose in A History of Indian Cricket. India won both ODI matches against the touring Pakistanis as well as the unofficial third match in Delhi, India’s first-ever floodlit game. “Crowd in large numbers came to these matches; but few came to the Tests that followed,” he wrote.

The crowd’s enthusiasm for the game’s shortened variety, their indifference to Tests and the ever-widening reach of television forced a BCCI strategic rethink. Right through the 1980s, hundreds of transmitters were set up nationwide drawing small towns and kasbahs into the television fold. TV was the new must-have gizmo for every middle-class home.

Substantial changes were made in the team’s playing calendar. Between 1974 and 1983, India had played roughly 5.5 games every year; between 1984 and 1989, the number

vaulted to 19 games annually.

Cricket on television soon emerged as a market rival to cinema.

Two months before the 1987 Reliance World Cup (Oct 1-Nov 9), Film Information, a trade magazine, noted, “This being the biggest opposition one can think of, no major film will be released during this period.”

Post-1983, the gap between cricket and other sports widened. Football had failed to produce anything spectacular even at the Asian level in the 1980s. Hockey had the 1975 World Cup victory and the 1980 Olympic gold, admittedly in a shriveled field, to flaunt. But the 7-1 rout at the hands of firm foe Pakistan in the Delhi Asian

Games rankled many.

Aided by more market-savvy administrators, cricket would use lucrative television deals to hegemonise the sporting public’s mind even in smalltowns and kasbahs. With the coming of satellite television in 1991, TV deals would eventually graduate from rupee to dollars. The impact of cricket on TV would be seen in India’s next World Cup triumphs.

The winning squads of 2007 (T20) and 2011 (ODI) were led by small-towner MS Dhoni and filled with players with similar backgrounds such as Harbhajan, Raina, Sreesanth and Munaf Patel, who was born in south Gujarat’s Bharuch district just a few weeks after India’s 1983 triumph.

The 1983 victory also gave the Asian cricket boards the confidence to dream big. The first three editions of the World Cup were held in England. Now India and Pakistan joined hands to host the Reliance World Cup in 1987. This was the beginning of the shifting of global cricket’s power centre.

The bonding between the two South Asian neighbours would break due to matters beyond the pitch but BCCI would eventually emerge as the Big Daddy of world cricket. India now not only has a seat at the high table, but is pretty much the table itself.

Sadly, 1983 also marked the end of the age of innocence in Indian cricket. 1983 gave us heroes. India savoured the triumph for weeks; much like the lingering aftertaste of an unexpected but eventually delightful feast.

Lord’s has endured long enough in our consciousness for Bollywood to invest in a multi-million rupee film in 2020. In contrast, the stars of 2011 were playing in the IPL a week later.

The 1983 triumph showed us the shape of cricket’s future in India. It also ushered in the future.

For all the latest Sports News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.