In honoring Annie Ernaux, the literature Nobel Prize gets it exactly right

On the one hand, it couldn’t be more timely. Annie Ernaux, the 82-year-old French writer who won the Nobel Prize for literature this morning, is perhaps best known — in the United States, at any rate — for her 2000 book “Happening,” which chronicles the illegal abortion she underwent in 1963 at the age of 23 and inspired Audrey Diwan’s film of the same name. The movie was released here this past May, not long before the Supreme Court upended nearly half a century of federal protection for reproductive rights by striking down Roe vs. Wade.

In that sense, it hardly seems a stretch to suggest that the Swedish Academy, which administers the Nobel and in the past has used its selection process to make pointed political statements — Harold Pinter’s 2005 acceptance speech, for instance, framed a devastating critique of American foreign policy leading up to the invasion of Iraq — is doing something similar here.

At the same time, and as much as I support that intention, the choice of Ernaux as this year’s laureate is a victory for literature. First and foremost, it represents an overdue recognition of an author whose idiosyncratic brilliance has been, over the course of a nearly 50-year career, as bracing as it is rare. As I once wrote in these pages, Ernaux is ruthless, which is the highest praise I have to give. In more than 20 books, 15 of which have been translated into English, she has effectively deconstructed not just the memoir as a form but also the very question of memory and identity. “Maybe the true purpose of my life,” she observes in “Happening,” “is for my body, my sensations and my thoughts to become writing.”

What Ernaux is getting at is the idea that all of us, whether or not we write or read, re-create ourselves in language, in the stories by which we seek to shape our lives. The fact that these stories are conditional, subjective, sits at the center of Ernaux’s work. She is not interested in taking narrative at face value or using it to blur or soften; there is not a sentimental sentence in her oeuvre. Rather, she resists the idea that memory can be consoling — or even contained. “My mother died on Monday 7 April in the old people’s home attached to the hospital at Pontoise, where I had installed her two years previously,” she starts her 1987 reminiscence “A Woman’s Story,” which echoes Albert Camus’ opening sentence in “The Stranger”: “Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know.”

I use the word reminiscence rather than memoir for a reason; Ernaux also resists the simplification of form. Memoir comes with a set of baked-in expectations: that it will arc in some way, or build to resolution, which is the last thing the author has in mind. She knows, as both a human and a writer, that epiphany is a fiction, that writing at its best functions as excavation, confrontation — not least with everything we cannot rise above. Such an intention emerges in her first book, “Cleaned Out” (1974), which calls itself a novel even as it represents an early exploration of the material to which she would return in “Happening.”

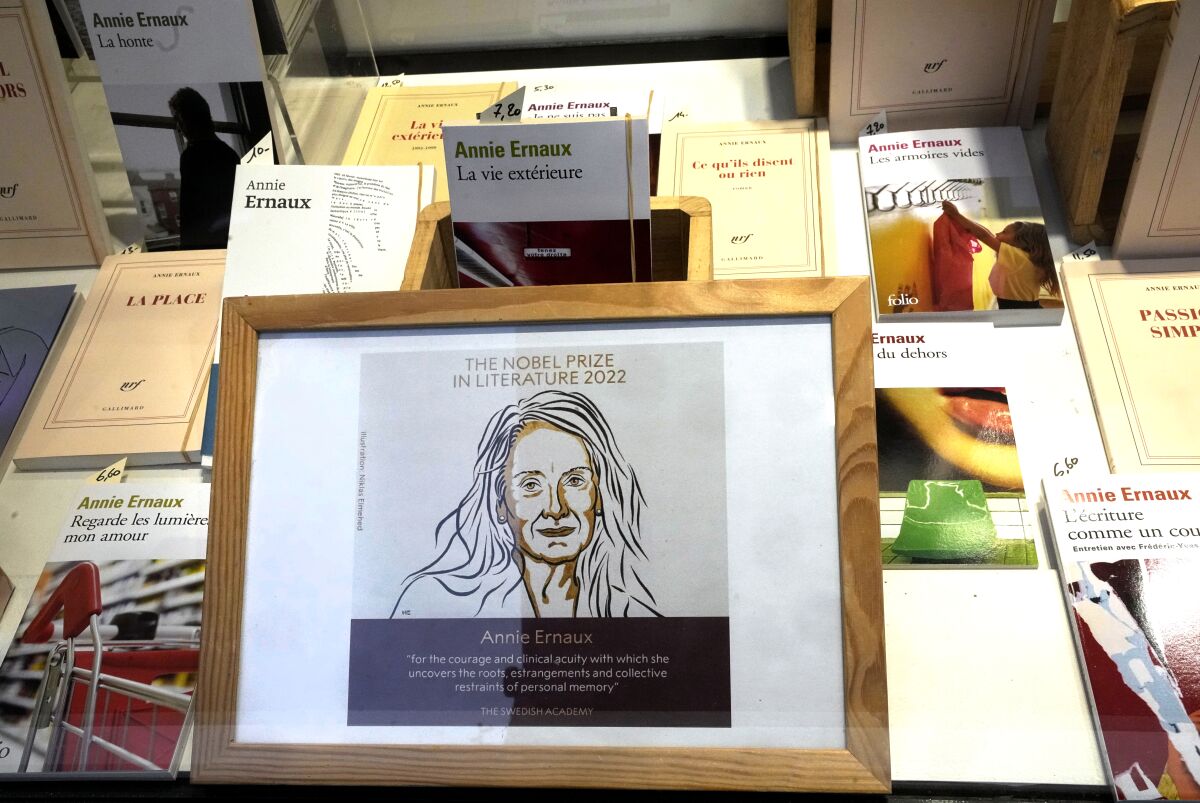

Books of Annie Ernaux on display in a library window in Paris. The 82-year-old was cited for “the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory,” the Nobel committee said.

(Michel Euler / Associated Press)

All these memories, all these experiences, swirl around each other in her imagination. “Trace it all back,” she writes in “Cleaned Out,” “call it all up, fit it all together, an assembly line, one thing after another. Explain why I am shut up here in a crummy dorm room, terrified of dying and of what’s going to happen. Figure it out, get to the bottom of it all between contractions. Find out where the whole mess began.” Life writing — in other words, autofiction — call it what you will.

Ernaux is not the first autofictionalist to win a Nobel. That would be Patrick Modiano, another French writer whose slim, impressionistic narratives trace a line between memory and place. But if Ernaux’s work recalls his in some sense, what distinguishes her writing is its abiding air of complicity. In a world where memory itself is conditional, how do we know anything? How do we know who we are? Ernaux’s books exist in the space opened up by these questions, framing narrative as inquiry rather than a statement of any kind.

Both “A Woman’s Story” and its companion volume “A Man’s Place” (1983) represent cases in point. On one level, each is about the death of a parent. On another, they are idiosyncratic explorations of grief. “A Man’s Place” is composed in retrospect, reflective if not exactly backward-looking. “It’s taken me a long time to write,” Ernaux admits. (Her father died in 1967.) “By choosing to expose the web of his life through a number of selected facts and details, I feel that I am gradually moving away from the figure of my father. The skeleton of the book takes over and ideas seem to develop of their own accord.”

A similar conundrum motivates “A Woman’s Story,” which unlike “A Man’s Place” unfolds almost entirely in real time. One of the ways Ernaux develops this book is to circle back, more than once, to the opening sentence, using it as a kind of echo that punctuates the narrative. “Tomorrow, it will be three weeks since the funeral,” she writes at one point. “It was only the day before yesterday that I overcame the fear of writing ‘My mother died’ on a blank sheet of paper, not as the first line of a letter but as the opening of a book.”

Such a move highlights not only the immediacy of writing as an act but also the emotions Ernaux can’t resolve. “I shall never hear the sound of her voice again,” she writes in the closing paragraph of “A Woman’s Story.” “It was her voice, together with her words, her hands, and her way of moving and laughing which linked the woman I am to the child I once was. The last bond between me and the world I come from has been severed.” It is, I think, the only way to end the book, with such an unrelenting word.

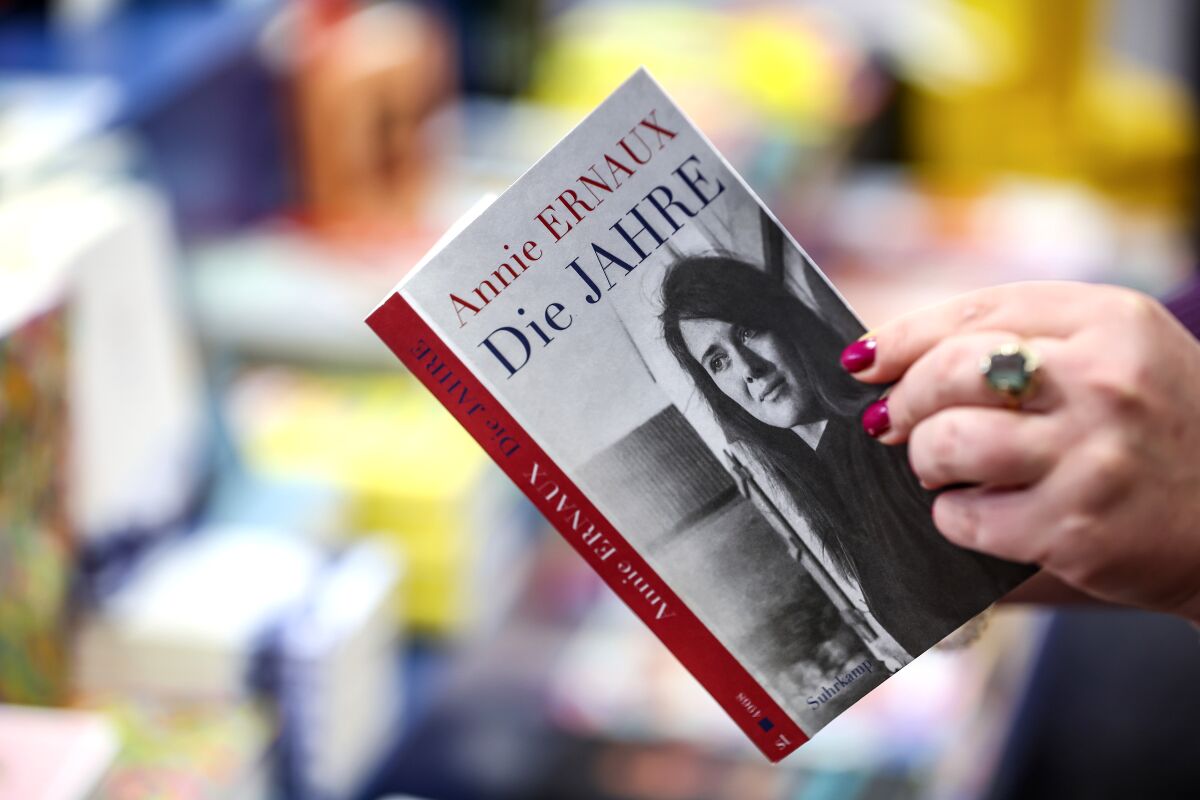

A woman opens “The Years” by Annie Ernaux in a bookstore in Leipzig, Germany. That memoir’s avoidance of the first-person “changes the game,” David Ulin writes, in a suitable capstone to her career.

(Jan Woitas / Associated Press)

Still, even as the author has been severed, her history — her memory — lingers. What to do about that? In “The Years” (2008), Ernaux addresses the issue head on, seeking out “a language no one knows.” The solution she enacts explodes our preconceptions of voice and person, sliding between the singular and plural, using pronouns such as “we” and “she” while eschewing the memoir’s defining posture: “I.”

Do I need to say how exciting this is? How this changes the game? By ceding the “I,” Ernaux effectively also cedes her own centrality, writing toward a perspective that is more collaborative — or, at least, more shared. A chorus in which individual experience becomes rendered as collective, and we are all implicated for good and ill.

That’s what makes her selection as laureate so exhilarating. It feels (I don’t know quite how else to say it) like an existential win. “No lyrical reminiscences, no triumphant displays of irony,” she insists in “A Man’s Place.” Simplicity of expression and clarity of voice. That’s the source of her genius, along with her unwillingness to take anything for granted, to let herself or anyone off the hook.

“This will not be a work of remembrance in the usual sense,” Ernaux reminds us in “The Years.” “It will be a slippery narrative composed in an unremitting continuous tense.” She may as well be describing her whole body of work.

Ulin is a former Books editor and critic for The Times.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.