In a New York cathedral, Joan Didion is memorialized — as a Californian

With the sun as bright as a typical day in Los Angeles, thousands of people gathered in New York on Wednesday to pay tribute to Joan Didion, the iconic author who died at 87 in December. The massive stone Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Divine was gray inside, and somber.

Didion had a particular affection for the cathedral; the Very Rev. Patrick Malloy told the audience that at a ceremony in April, the author’s ashes were placed in its columbarium. The cathedral also holds the ashes of her husband, John Gregory Dunne, and their daughter, Quintana Roo — subjects of Didion’s two great memoirs of mourning.

Speakers at Didion’s service included friends, family and fans, as did the audience, a mix of New York literati, Hollywood stars and the writers working today who owe a debt to Didion’s style, clarity and relentless craft. Vanessa Redgrave read, nephew Griffin Dunne remembered and Patti Smith sang.

Among the most surprising people to take the stage were former Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, who knew Didion when they were children in Sacramento, and former California Gov. Jerry Brown (via a taped video), who had stayed with Didion and Dunne in New York during his 1992 presidential campaign.

For those who knew Didion only through her writing, it was an opportunity to get a glimpse behind the guarded candor of her nonfiction. Actor and director Griffin Dunne recalled meeting his aunt Joan for the first time — she didn’t join those laughing at him when he had a bathing suit mishap. He directed the 2017 documentary “Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold.” Although they discussed some “desperately sad subjects” in the film, Dunne said, “Working with her was one of the highlights of my life.”

Writer Susanna Moore, best known for her novel “In the Cut,” drew life lessons from her decades-long friendship with Didion: the social observations from 1960s Los Angeles, including “Evil is the absence of seriousness” and “Crazy is never interesting.” The acidic cautions: “Drop the whole idea of knowing the truth,” “Whatever you do, you’ll regret both,” “Stop running away.” Most brutal and useful for an author: “Write it again.”

Actress and filmmaker Susan Traylor, who was friends from childhood with Quintana Roo, revealed a different side of Didion. She spoke of the laughter and cheer at their family dinners, of feeling protected by Didion’s nurturing side.

In addition to providing a peek at the private Didion, the memorial celebrated her work, which spanned six decades of nonfiction and fiction. Calvin Trillin read from one of her essays. Jia Tolentino spoke of her influence. Hilton Als described her coming into her own. All three writers are on staff at the New Yorker, a mismatch not lost on the magazine’s editor, David Remnick, who also spoke.

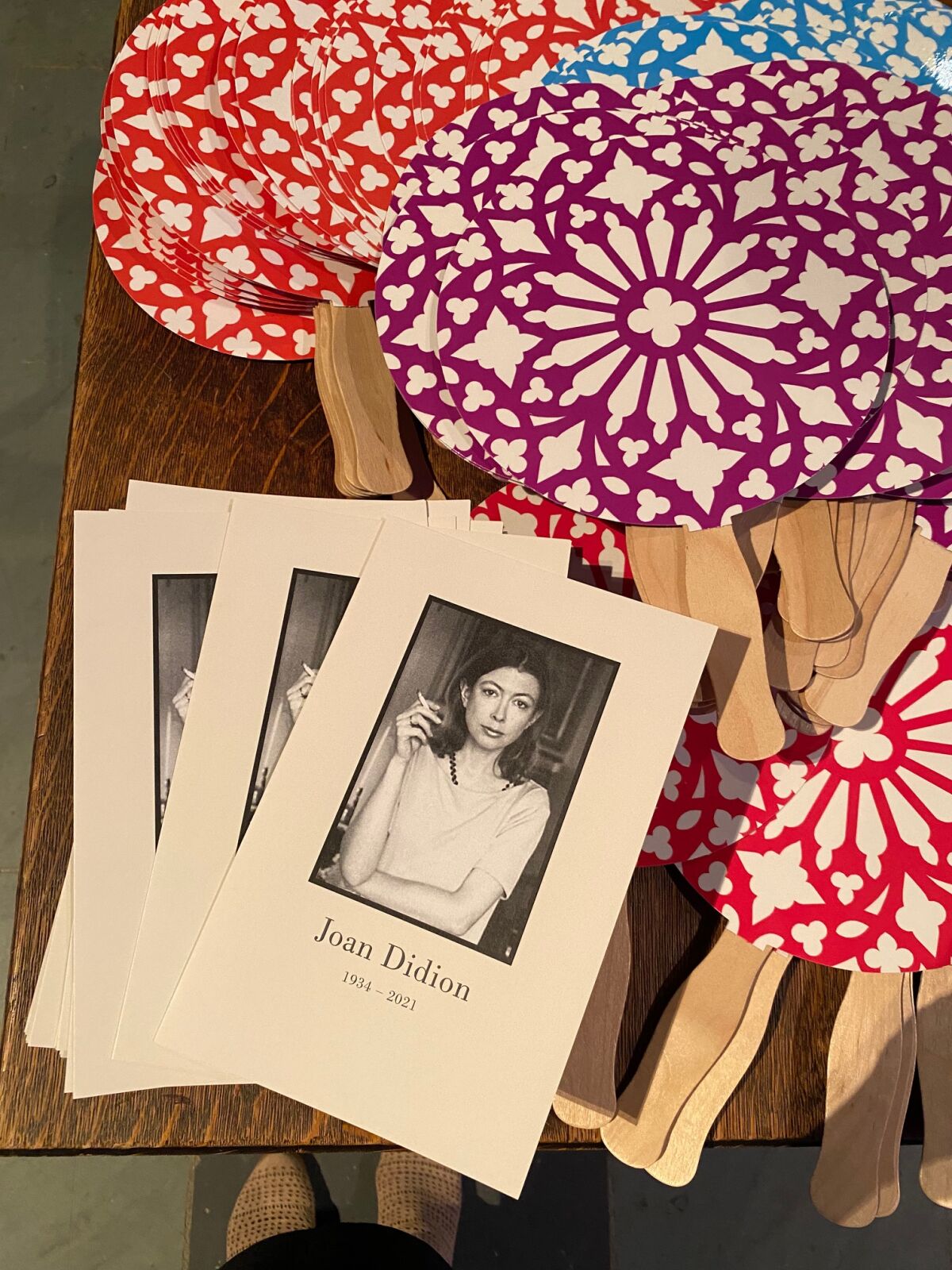

An assortment of programs and hand fans greeted guests at Wednesday’s memorial tribute to Joan Didion at New York’s Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

(Carolyn Kellogg)

“I was rarely fortunate enough to publish Joan Didion,” Remnick admitted. “When Joan took time to write for magazines, she almost always did so — brilliantly, daringly, and with an overwhelming sense of security — for Bob Silvers at the New York Review of Books. Of course Bob is among the missing today, and when it comes to the world of Joan Didion, the cathedral is crowded with ghosts. Bob. Barbara Epstein. Jason Epstein. Susan Sontag. Nora Ephron. Toni Morrison.”

Didion frequently brought a personal edge to her nonfiction, but when her husband died of a heart attack in 2003, she brought a new level of vulnerability to her writing. Her memoir about what happened next, “The Year of Magical Thinking,” won the National Book Award for nonfiction, became a bestseller and was turned into a play by David Hare starring Vanessa Redgrave.

Redgrave took the stage at the cathedral with the aid of her son-in-law Liam Neeson, who carried a book bag for her. From it she took a hardcover. “Joan Didion. The Year of Magical Thinking. Signed at Book Soup,” Redgrave declared. The audience laughed, as if Book Soup was a silly name. “In Los Angeles,” she added, seriously. Redgrave spoke about the making of the play, and Didion’s attendance, eating dinner in the wings offstage.

The slideshow before the event began had included photos of Didion and Redgrave at that time. In one, Didion looked thin and frail, tiny on a couch next to the robust Redgrave. But now the Oscar-winning actress, though still striking and able to galvanize a room at 85, seems frail. It was a painful reminder of what a memorial like this is about — time. And how art survives.

Literary New York and California both tried to claim Didion as one of their own during her lifetime. She was born and raised in Sacramento, moved to New York City, moved to Los Angeles, then moved back to New York. She was a native Californian, yes, but by the numbers and by choice, New York was her home.

After the memorial, I wanted to find out what her friends and admirers thought: Was Joan Didion a New Yorker or a Californian?

Humorist and über-New Yorker Fran Lebowitz, who’d been in the audience, was outside having a cigarette. “California,” she said, before I could finish my question. “I know she lived in New York, but [California] would be the first thing I would think about Joan. I know that many people would be angry about this — although many of them are dead — there are no other writers from California of that era.” (Lebowitz’s favorite piece by Didion is “Trouble in Lakewood” from 1993, about the Spur Posse, class and America.)

I found Trillin inside. “I think Californian,” he said carefully. “I visited her in both places. You know she used to go back to the house she grew up in to finish books.”

At that moment, Carl Bernstein walked up, and after thanking him for his work, I asked him the same question. He didn’t hesitate. “In both places,” he said, “she was the greatest reporter of our time.”

Earlier, Patti Smith had closed the event with the Bob Dylan song “Chimes of Freedom,” accompanied only by Tony Shanahan on acoustic guitar. It was a transcendent performance, beautiful and haunting and powerful. When it concluded, there was no applause. Just the echo of the cathedral, and the shuffling of a crowd that knew it was time to go.

Kellogg is a former book editor at The Times.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.