‘I’m afraid for her life’: Riverside women’s coach harassed in equality fight

Cheryl Miller is livid, her voice rising, her words coated with frustration, alarm and incredulity. The ire of one of the greatest women’s basketball players of all time is locked on the plight of a junior college coach in Miller’s hometown of Riverside.

“Right now, I’m afraid for her life,” Miller said. “She has way too much fight and she’ll fight and fight and fight, not for herself, but for her players. My greatest concern is for her safety. Absolutely. Someone will end up hurting her.”

Miller pauses to breathe. “If that happens, if somebody doesn’t step up and protect her, I will hold all of Riverside City College accountable.”

Outwardly, Alicia Berber doesn’t behave like someone under attack. She shows up for work every day, teaches classes and coaches the women’s basketball team, same as she’s done for 22 years. The Riverside City College campus is her turf. She played basketball there as Alicia Rubio, was a Kodak All-American and was inducted into the school’s sports hall of fame in 2007.

But these days, Berber heads home before dark. She listens for footsteps before exiting her office, makes sure her car keys are in her hand and hurries to the parking lot. A fellow coach suggested she arm herself with pepper spray and a taser.

She says she’s been berated and ostracized for years, treatment that she alleges recently escalated to bullying and verbal threats by a small handful of male athletes. Her offense? Berber had the temerity to insist, no, to demand, that Riverside City College follow Title IX regulations to the letter, that her team get the exact same treatment as men’s teams. Then nearly a decade later, she insisted again.

Berber sued the college and agreed to a $250,000 settlement in 2012. As part of the pact, two negative evaluations of Berber contrived by athletic director Barry Meier — who subsequently was put on administrative leave and resigned after pornography was reportedly discovered on his work computer — were rescinded and the college promised to conduct “sensitivity and sexual harassment training to all athletic department staff in conjunction with a mandatory staff meeting.”

Berber thought maybe her fight for equality was over. But, she alleges, violation after violation, humiliation after humiliation, year after year, made her professional life miserable. So, she fought back — again.

“In Riverside it’s really a deep-rooted culture, it’s an old boys network,” she said. “I’m breaking that up and I’m proud to say I’m breaking that up. When I decide to retire, I want the young woman or man that wants to take over the team to have an opportunity to coach without the conditions I’ve had to deal with for so many years.”

She filed a second lawsuit on July 19, 2021, after incidents she and her supporters allege were further violations of Title IX, the federal law enacted in 1972 to protect people in education programs from sex-based discrimination. The lawsuit lists four breaches of the California Fair Employment and Housing act as complaints for damages, including discrimination based on sex and failure to prevent retaliation for reporting and opposing discrimination. A trial is scheduled for next summer.

Violations described in the lawsuit focus mainly on Berber’s futile efforts to get her team equal access to the weight room, her getting passed over for classes she wanted to teach in favor of assistant football and baseball coaches with less experience. The suit alleges that “since settling her discrimination/retaliation lawsuit against RCCD in 2012, (and even before then), the District has continued to victimize Ms. Berber and support other staff in doing the same. At faculty meetings, Ms. Berber is routinely ostracized, ignored, belittled, and isolated.”

Berber says bullying and intimidation have increased since she filed the second lawsuit. She says football coaches and players are routinely dismissive of the women athletes and men’s basketball players have rudely pressured the women’s team to end practice early so they can use the court. Berber said that a month ago a men’s basketball player walked closely behind her in a hallway and said, “There’s the big, bad wolf.”

Current RCC athletic director Payton Williams, a Riverside native who played two years in the NFL, declined to comment because of Berber’s pending litigation.

In January 2022, several football players barged into the weight room while the women’s basketball players were working out during their assigned time and removed weights from the room without asking permission.

“That pushed it into high gear for me,” Berber said. “Where it hit and exploded was when they had total disregard for my student-athletes. The men always have time in the weight room. We could never get in there. And they finally gave us an opportunity, and the football players didn’t like it and took weights out of the room.”

Riverside City College women’s basketball coach Alicia Berber directs her players during a game against Santa Monica City College on Dec. 8.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Berber said two men’s basketball players in particular have bullied and intimidated her and her players because this season the women’s team was given an earlier practice time previously reserved for the men. Although none of the women’s players have made allegations of harassment, they say that during women’s practices, men’s players have loudly thrown basketballs against the gym door and yelled for the women to finish practice so they can take the floor.

The relationship between the teams is complicated because many of the men and women are friends.

“I think overall the men’s team, they support us, I’m friends with a few of them,” said Shanon Jordan, a sophomore guard. “You know there are a couple bad apples, everyone’s not perfect, but most of the players, they are definitely with us.”

It’s the “bad apples” that Berber says she fears. In addition to allegations outlined in the lawsuit, she has expressed concern for her own safety to top RCC administrators.

FeRita Carter, RCC’s interim president since October, said through a statement that campus police are responsible for protecting employees and students. Once a report is received, “a multi-pronged approach by campus police, student services, academic affairs and other areas of the college … is taken to resolve issues and concerns.”

Berber, 47, said she reported the incidents to the campus police department sergeant, who dispatched an officer to oversee the women’s next practice. The sergeant also told Berber to call the department any time she needs an escort to her car, although men’s coach Phil Mathews vehemently denies that his players are guilty of harassment or retaliation.

“We have an all-Black team, [Berber] is trying to criminalize these guys and I’m not going to allow that to happen,” Mathews said. “She’s using code words. ‘Violently.’ ‘I’m afraid for my safety.’ Those are code words.”

Mathews, 72, has coached for 50 years, including three as a UCLA assistant, nine as head coach at the University of San Francisco as well as the last 10 at RCC. He is known as a disciplinarian with a track record of giving players second chances and succeeding at the junior college level.

“For her to say she is scared, this is Riverside City College. I went to school here,” he said. “I don’t believe it, not coming from my program.”

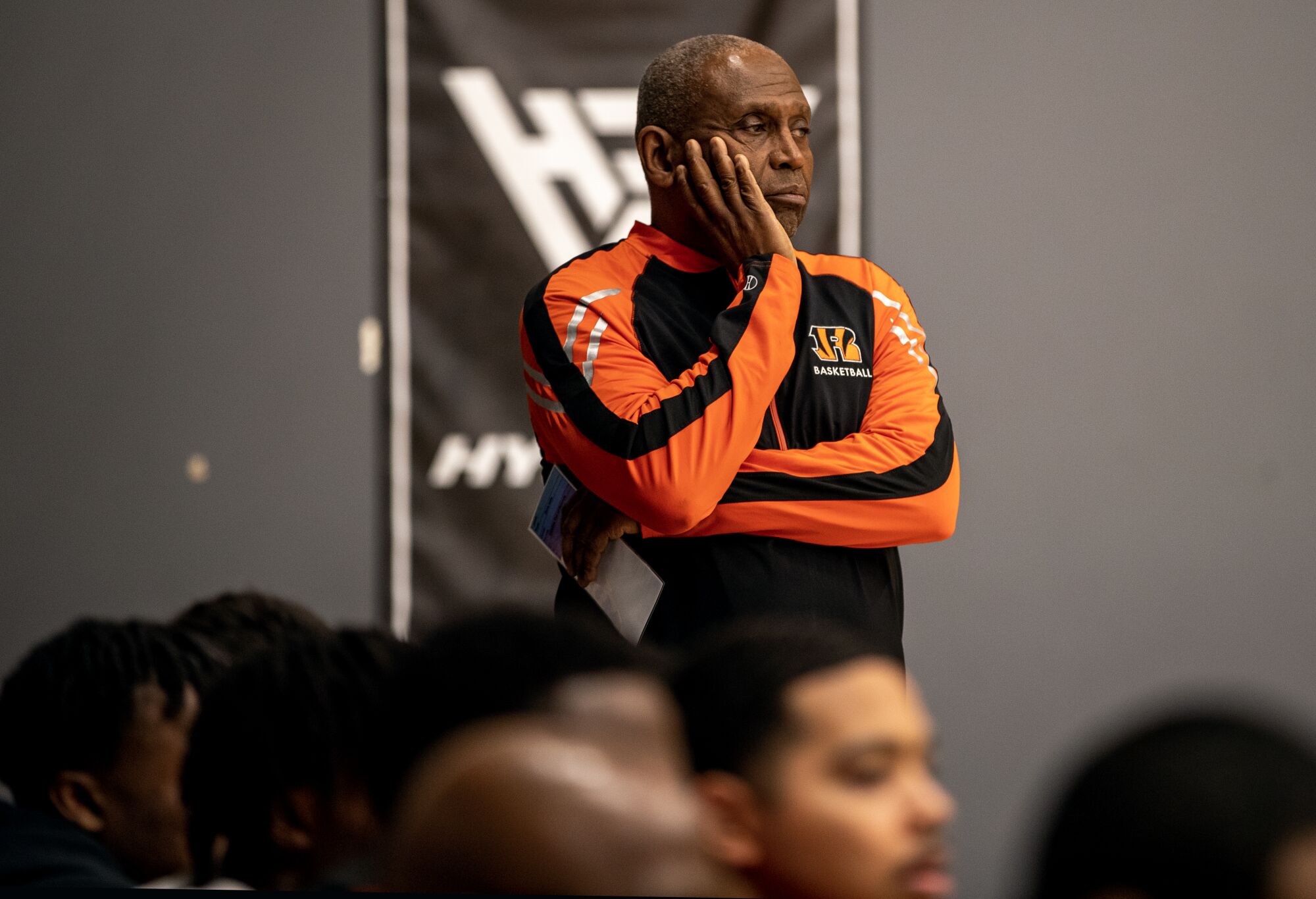

Riverside Community College basketball coach Phil Mathews watches from the bench during a game against Ventura on Dec. 30.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Mathews recently hung two banners in Riverside’s Wheelock Gym that read “Riverside City College Men’s Basketball celebrates the 50th anniversary of Title IX and its impact on college sports” in response to Berber hanging similar banners. Berber is happy four banners in the gym celebrate Title IX but she isn’t sure whether Mathews’ gesture was sincere or mocking the women’s efforts.

“Title IX covers men too,” Mathews said. “Alicia gets exactly what I get, no more, no less.”

Berber said she is repeatedly met with resentment and retaliation for shedding a spotlight on problems hidden in a long-neglected corner of the sports landscape: Junior college sports don’t get much media attention or draw large crowds, especially the women’s teams.

Berber’s plight has drawn the support of several prominent female athletes and Title IX advocates, including tennis icon and part owner of the Dodgers Billie Jean King and four-time UCLA All-American Ann Meyers Drysdale.

Of course, Miller, a Naismith Hall of Fame inductee, four-time USC All-American and Riverside native, remains riveted. She recalls meeting Berber for the first time while recruiting as coach of Langston University in 2014.

“I walked into Alicia’s office and she had two ice packs on her knees,” Miller said. “I’m thinking, ‘She’s a baller.’ We started talking and she is the most genuine human being. You don’t meet many people like that, and that’s why I feel so passionate. I will fight for her, period.”

Title IX was signed into legislation in 1972, but its 50th anniversary last year triggered as many sighs as celebrations. Certainly, barriers toppled and glass ceilings shattered were noted. But for women across the national sports landscape, the anniversary served as a sober reminder of how much still needs to be done.

An overriding concern is that schools routinely ignore Title IX with zero repercussions, according to experts. Violations are reported to the federal Office for Civil Rights (OCR), an underfunded and understaffed agency within the Department of Education that rarely punishes schools.

Three members of the U.S. House of Representative sent a letter to NCAA President Mark Emmert last March, criticizing him for failing to take meaningful steps to ensure gender equity and suggesting the NCAA is in violation of Title IX.

Then-representatives Carolyn B. Maloney (D–N.Y.), Jackie Speier (D–Hillsborough) and current representative Mikie Sherrill (D–N.J.) said the NCAA failed to implement recommendations from an external review prompted by disparities between men’s and women’s players exposed during March Madness in 2021. Among a litany of concerns, women players pointed out that their locker room and weight room facilities were vastly inferior to those of the men.

“It was a little disheartening because from the NCAA what was communicated to us was we really weren’t as valued as the male athletes in the discrepancies from the weight room, the swag bag and the food,” then-UCLA star Michaela Onyenwere told The Los Angeles Times. “It just reaffirmed to me that it’s the world we’re living in as female athletes.”

The OCR is required by federal law to seek a voluntary resolution with schools that violate Title IX, obtaining a commitment to comply then monitoring implementation of the corrective action. An offending school theoretically could be denied federal funds, but that is an action the OCR has never taken.

Lawsuits like Berber’s generally elicit a quicker response from schools, although lawyers are often reluctant to take Title IX cases because they rarely result in a significant monetary award. Many cases are filed by nonprofit advocates for women and lawyers take them on a pro bono basis, getting paid only if a lawsuit is successful and a school is ordered to pay attorney fees.

Judith Sweet, who became the first woman to serve as president of the NCAA in 1991, has been an ardent supporter of Title IX enforcement for decades. She believes what separates Berber from many other coaches and athletes who experience discrimination and retaliation is her persistence.

“I’ve heard stories from women coaches throughout the country about the lack of support from administrators, Title IX violations, and retaliations if they spoke up about them,” said Sweet, who is retired and living in San Diego. “A lot of coaches I heard from were run out of the profession. They didn’t have the persistence and strength to put up with that kind of abuse.

“That’s where Alicia is different. She stayed the course for the length of time she has been mistreated. She’s shown unbelievable strength and has been so badly treated. I shake my head, that a college from top to bottom would allow such bad behavior to occur.”

Riverside City College women’s basketball coach Alicia Berber says she’s proud to be breaking up the “old boys network” at Riverside Community College.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

The suit also alleges that Steve Sigloch, the chair of the kinesiology department and a former player and coach under former athletic director Meier, “time after time, installed his friends and male coaches to the best positions, classes, and instructional time slots, overlooking Ms. Berber and leaving her and her female students to fend for themselves.” Sigloch did not return two emails asking for comment.

Carter, the interim president, while declining to comment specifically on Berber’s lawsuit, said RCC is “fully committed to treating all of our students, faculty, and staff in an equitable and fair manner. I am a strong advocate of the rights of women and all other populations that are protected by Title IX laws and statutes.”

The video posted on social media by the RCC women’s basketball team in February features 11 players standing in the weight room in workout attire, chanting in unison with purposeful expressions on their faces.

We deserve to be here. We need the weight room. Our voices deserve to be heard. As women, we deserve equality. Our strength starts with our voice. We want respect, not apologies. Equality is not subjective. We deserve to be here.

The team created a Twitter account, @EqualityinWS, and made T-shirts that read “Equality in Women’s Sports” on the front and “We Deserve to Be Here” on the back.

“We believe women should have equal opportunities, and just for [Berber] to let us know what she’s been through really motivated us to make change ourselves,” team captain Elizabeth Lau told RCC student publication Viewpoints at the time. “I don’t want to wait another 20 years when my daughter comes home and is like, ‘They don’t let me use the weight room, mom.’”

RCC and its opponent, Orange Coast College, wore the T-shirts before RCC’s last home game of the 2021-22 season in what they dubbed a protest game. More than 500 fans attended the game, although Berber said more were left outside the gym because Williams — who had been hired as athletic director only a month earlier — had men’s basketball players block the doors, saying no one else could enter the gym because of COVID-19 restrictions.

“They were trying to deter everyone possible from getting into the game,” Berber said.

A week later, the men’s team had a home playoff game. The women’s team was settling in to watch when Williams told them they had to leave the gym and could only return if they paid admission despite a state community college rule that coaches are honored with complimentary passes.

A player called Berber, who said, “Don’t move, I’ll be right there.” She drove to the school and paid for her players to reenter the gym.

Micheal Barnes, the RCC women’s coach for 20 years until he retired and turned the program over to Berber, said never had women players been asked to pay to watch a men’s home game. He believes doing so was payback for the lawsuit and holding the protest game.

Players on the Riverside City College women’s basketball and coach Alicia Berber, second from right, stand during the playing of the national anthem before a game.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

“[Williams] would never have done that to the men’s team,” Barnes said. “What a double standard. What a hypocrite.”

This season began with a Berber brainstorm, the Title IX Tipoff, originally set to take place at Wheelock Gym on Oct. 15. However, a men’s basketball scrimmage was scheduled for that afternoon, administrators wouldn’t reschedule it, and Mathews declined Berber’s invitation for the men’s team to join in the celebration of the 50th anniversary of Title IX.

Berber said she couldn’t change the date because she had commitments to participate from Miller, Meyers Drysdale and a Drew League women’s team of WNBA players. “Clipper Darrell” would handle the mic. So Berber moved it to Riverside Ramona High School, where a clinic for youth players was scheduled to take place during the afternoon.

“The most common-sense thing was that our men’s team get involved, but there was nothing like that,” Berber said. “I didn’t care if I had to go to a park to hold the Title IX event. It was going to happen.”

RCC players helped run the clinic. Then a junior high travel team took the court for a game followed by the Drew League team. Miller and Meyers Drysdale addressed the crowd.

“For those girls at the clinic, the message was amazing,” Berber said. “First they learn fundamentals from college and high school players, then they see travel ball, then they hear from two Hall of Famers and see that you can become a professional. How cool is that?”

Former WNBA coach Cheryl Miller, center, sits next to Riverside Community College women’s basketball coach Alicia Berber, right, at a game between the New York Liberty and Connecticut Sun on June 22.

(M. Anthony Nesmith / Icon Sportswire via Getty Images)

RCC took the momentum into the season and is 15-5. Berber said the drama associated with her lawsuit and battles against Title IX violations haven’t impacted recruiting. To her players, Berber’s ordeal has been nothing less than a firsthand, real-world education in the struggle against discrimination and retaliation.

“She has been here for over 20 years, so I think over time she has learned, and she sees the signs,” Jordan said. “She’s trying to nip it in the bud before it gets even bigger. And I really respect that. A lot of people would just let things go on and on and on, and she wants to stop it right now. Because we deserve that.”

Berber has company in her quest for equality — her husband and two children, her coaching staff and, especially, her players.

“I’ve never been prouder of those young women,” Berber said. “The culture focused on men’s sports needs to change, and it needs a voice, and my student-athletes have been that voice.”

And when a more forceful voice is called upon, Cheryl Miller will gladly oblige.

“Coach Berber did the unthinkable, she stood up for herself,” Miller said. “Her daughter knows that mom is fighting. Her son and her husband know she is fighting.

“So many women, my colleagues, we have been kicked into the teeth for so long. I’m done. So is Alicia. And that’s why she’s trying to make sure it’s not going to happen any more.”

For all the latest Sports News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.