How Bob Dylan used practice of ‘imitatio’ to craft some of the most original songs of his time

Bob Dylan will share his thoughts on the music of a wide range of artists in a new essay collection titled “The Philosophy Of Modern Song.”

Over the course of six decades, Bob Dylan steadily brought together popular music and poetic excellence. Yet the guardians of literary culture have only rarely accepted Dylan’s legitimacy.

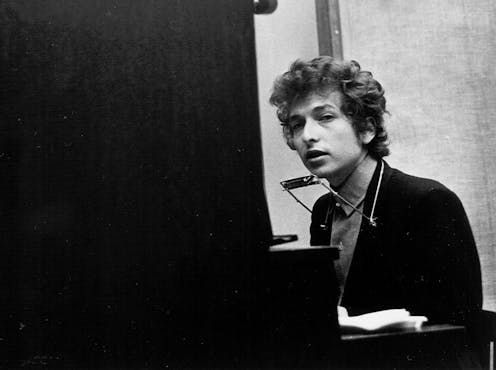

Dylan’s complex creative process is unique among contemporary singer-songwriters. Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Dylan’s complex creative process is unique among contemporary singer-songwriters. Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

His 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature undermined his outsider status, challenging scholars, fans and critics to think of Dylan as an integral part of international literary heritage. My new book, “No One to Meet: Imitation and Originality in the Songs of Bob Dylan,” takes this challenge seriously and places Dylan within a literary tradition that extends all the way back to the ancients.

People are also reading…

I am a professor of early modern literature, with a special interest in the Renaissance. But I am also a longtime Dylan enthusiast and the co-editor of the open-access Dylan Review, the only scholarly journal on Bob Dylan.

After teaching and writing about early modern poetry for 30 years, I couldn’t help but recognize a similarity between the way Dylan composes his songs and the ancient practice known as “imitatio.”

Poetic honey-making

Although the Latin word imitatio would translate to “imitation” in English, it doesn’t mean simply producing a mirror image of something. The term instead describes a practice or a methodology of composing poetry.

The classical author Seneca used bees as a metaphor for writing poetry using imitatio. Just as a bee samples and digests the nectar from a whole field of flowers to produce a new kind of honey — which is part flower and part bee — a poet produces a poem by sampling and digesting the best authors of the past.

To Seneca, the poetry writing process was akin to a bee making honey. K_Thalhofer/iStock via Getty Images

To Seneca, the poetry writing process was akin to a bee making honey. K_Thalhofer/iStock via Getty Images

Dylan’s imitations follow this pattern: His best work is always part flower, part Dylan.

Consider a song like “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” To write it, Dylan repurposed the familiar Old English ballad “Lord Randal,” retaining the call-and-response framework. In the original, a worried mother asks, “O where ha’ you been, Lord Randal, my son? / And where ha’ you been, my handsome young man?” and her son tells of being poisoned by his true love.

In Dylan’s version, the nominal son responds to the same questions with a brilliant mixture of public and private experiences, conjuring violent images such as a newborn baby surrounded by wolves, black branches dripping blood, the broken tongues of a thousand talkers and pellets poisoning the water. At the end, a young girl hands the speaker — a son in name only — a rainbow, and he promises to know his song well before he’ll stand on the mountain to sing it.

“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” resounds with the original Old English ballad, which would have been very familiar to Dylan’s original audiences of Greenwich Village folk singers. He first sang the song in 1962 at the Gaslight Cafe on MacDougal Street, a hangout of folk revival stalwarts. To their ears, Dylan’s indictment of American culture — its racism, militarism and reckless destruction of the environment — would have echoed that poisoning in the earlier poem and added force to the repurposed lyrics.

Drawing from the source

Because Dylan “samples and digests” songs from the past, he has been accused of plagiarism.

This charge underestimates Dylan’s complex creative process, which closely resembles that of early modern poets who had a different concept of originality — a concept Dylan intuitively understands. For Renaissance authors, “originality” meant not creating something out of nothing, but going back to what had come before. They literally returned to the “origin.” Writers first searched outside themselves to find models to imitate, and then they transformed what they imitated — that is, what they found, sampled and digested — into something new. Achieving originality depended on the successful imitation and repurposing of an admired author from a much earlier era. They did not imitate each other, or contemporary authors from a different national tradition. Instead, they found their models among authors and works from earlier centuries.

In his book “The Light in Troy,” literary scholar Thomas Greene points to a 1513 letter written by poet Pietro Bembo to Giovanfrancesco Pico della Mirandola.

“Imitation,” Bembo writes, “since it is wholly concerned with a model, must be drawn from the model … the activity of imitating is nothing other than translating the likeness of some other’s style into one’s own writings.” The act of translation was largely stylistic and involved a transformation of the model.

Romantics devise a new definition of originality

However, the Romantics of the late 18th century wished to change, and supersede, that understanding of poetic originality. For them, and the writers who came after them, creative originality meant going inside oneself to find a connection to nature.

As scholar of Romantic literature M.H. Abrams explains in his renowned study “Natural Supernaturalism,” “the poet will proclaim how exquisitely an individual mind … is fitted to the external world, and the external world to the mind, and how the two in union are able to beget a new world.”

Instead of the world wrought by imitating the ancients, the new Romantic theories envisioned the union of nature and the mind as the ideal creative process. Abrams quotes the 18th-century German Romantic Novalis: “The higher philosophy is concerned with the marriage of Nature and Mind.”

The Romantics believed that through this connection of nature and mind, poets would discover something new and produce an original creation. To borrow from past “original” models, rather than producing a supposedly new work or “new world,” could seem like theft, despite the fact, obvious to anyone paging through an anthology, that poets have always responded to one another and to earlier works.

Dylan performed at New York City’s Gaslight Cafe, a popular folk music venue. Bettmann/Getty Images

Unfortunately — as Dylan’s critics too often demonstrate — this bias favoring supposedly “natural” originality over imitation continues to color views of the creative process today.

For six decades now, Dylan has turned that Romantic idea of originality on its head. With his own idiosyncratic method of composing songs and his creative reinvention of the Renaissance practice of imitatio, he has written and performed — yes, imitation functions in performance too — over 600 songs, many of which are the most significant and most significantly original songs of his time.

To me, there is a firm historical and theoretical rationale for what these audiences have long known — and the Nobel Prize committee made official in 2016 — that Bob Dylan is both a modern voice entirely unique and, at the same time, the product of ancient, time-honored ways of practicing and thinking about creativity.

Raphael Falco does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Photos: Bob Dylan through the years

Folk singer and songwriter Bob Dylan plays the harmonica and acoustic guitar in March 1963 at an unknown location. He was born in Duluth, Minnesota in 1941 as Robert Allen Zimmerman. (AP Photo)

FILE – Musician Bob Dylan appears in London on April 27, 1965. Transcripts of lost 1971 Dylan interviews with the late American blues artist Tony Glover and letters the two exchanged reveal that Dylan changed his name from Robert Zimmerman because he worried about anti-Semitism, and that he wrote “Lay Lady Lay” for actress Barbra Streisand. The items are among a trove of Dylan archives being auctioned in November 2020, by Boston-based R.R. Auction. (AP Photo, File)

American singer Bob Dylan at a press conference in Paris, France on May 22, 1966. (AP Photo/Pierre Godot)

Singer Bob Dylan entertains at the Forum in Los Angeles, Feb 15, 1974. (AP Photo/Jeff Robbins)

Singer Bob Dylan and appears before a full house at Madison Square Garden in New York, Jan. 31, 1974. He is on tour with his back up group The Band. (AP Photo/Ray Stubblebine)

Bob Dylan is back on the road with his show visiting small town and cities. He is seen here with Joan Baez, Nov. 4, 1975 in Providence, R.I. (AP Photo)

FILE- In this Dec. 8, 1975 file photo, Bob Dylan performs before a sold-out crowd in New York’s Madison Square Garden. Dylan’s entire catalog of songs, which spans 60 years and is among the most prized next to that of the Beatles, is being acquired by Universal Music Publishing Group. The deal covers 600 song copyrights. (AP Photo/Ray Stubblebine, File)

Folk singer Bob Dylan sings on stage during his final appearance with “The Band” at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco, Calif., on Thanksgiving Day, Nov. 25, 1976. The show was known as “The Last Waltz”. (AP Photo)

American singer Bob Dylan during his tour through West Germany at the Dortmunder Westfalenhalle, June 27, 1978. (AP Photo/Proepper)

American Singer Bob Dylan during his tour through West Germany at the Dortmunder Westfalenhalle, June 27, 1978. (AP Photo/Proepper)

Bob Dylan accepts a Grammy Award for his song “Gotta Serve Somebody” at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, Feb. 27, 1980. Presenters Ted Nugent and Michelle Phillips look on at right. Woman at left is unidentified. (AP Photo/Lennox McLendon)

American singer Bob Dylan performs at the Olympic Stadium in Colombes, France, before an estimated 40,000 fans, June 23, 1981. (AP Photo)

Singer Bob Dylan (left) at the Bar Mitzvah of his son (right) at the Wailing Wall, a Jewish Shrine in Jerusalem, Sept. 20, 1983. (AP Photo/Zavi Cohen)

American Folk singer during his show June 20 1984, in front of some 13,000 fans at Rome’s Palasport. ( AP Photo/Gianni Foggia)

American singer-songwriter Bob Dylan eyes the crowd while performing at the Live Aid famine relief concert at JFK Stadium in Philadelphia Pa., July 13, 1985. (AP Photo/Amy Sancetta)

Bob Dylan and Tom Petty, left, open their “True Confessions Tour” in the San Diego Sports Arena, June 10 1986 to a crowd of about 13,000. (AP Photo/Howard Lipin)

Bob Dylan receives The Founders Award from Hal David, president of the American Society of Composers, March 31,1986. (AP Photo/Nick Ut)

Singer/songwriter Bob Dylan opens his “True Confessions” tour in the San Diego Sports Arena to a sold-out house of about 17,000, June 9, 1986. It is Dylan’s first U.S. tour since 1981. Also appearing with Dylan is Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. (AP Photo/Howard Lipin)

Bob Dylan in concert, Aug 3, 1986. (AP Photo/Nick Ut)

Bob Dylan sings during his anniversary concert at New York’s Madison Square Garden, Friday night, Oct. 17, 1992. Joined by contemporary artists, Dylan celebrates the 30th anniversary of the release of his first Columbia album. (AP Photo/Ron Frehm)

American pop legend Bob Dylan sings “Knocking on Heavens doors” in front of Pope John Paul II during a concert in honour of the Pontiff in Bologna Saturday, September 27, 1997. An estimated crowd of 300,000 youths attended the concert. (AP Photo/Gianni Schicchi)

** FILE ** Bob Dylan performs at the Newport Folk Festival in this file photo from Aug. 3, 2002, in Newport, R.I. (AP Photo/Michael Dwyer, File)

US musician Bob Dylan, 69, performs with his band at his first one night only concert named “Bob Dylan – Live in Vietnam,” a one night only show held at RMIT University in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, Sunday, April 10, 2011. After nearly five decades of singing about a war that continues to haunt a generation of Americans, legendary performer Bob Dylan is finally getting his chance to see Vietnam at peace, 36 years after the end of Vietnam war. (AP Photo/Le Quang Nhat). (AP Photo/Le Quang Nhat)

FILE – In this June 18, 2011 file photo, U.S. musician Bob Dylan performs weeks after his 70th birthday at the London Feis Festival at Finsbury Park. (AP Photo/Joel Ryan, File)

FILE – In this Jan. 12, 2012 file photo, Bob Dylan performs in Los Angeles. One of the most popular songs of all time, Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” could bring between $1 million and $2 million at auction. (AP Photo/Chris Pizzello, File)

Bob Dylan performs during the 17th Annual Critics’ Choice Movie Awards on Thursday, Jan. 12, 2012 in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Chris Pizzello)

President Barack Obama presents rock legend Bob Dylan with a Medal of Freedom, Tuesday, May 29, 2012, during a ceremony at the White House in Washington. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak)

FILE – In this Jan. 12, 2012 file photo, Bob Dylan performs in Los Angeles. President Barack Obama and first lady Michelle Obama will honor a diverse cross-section of political and cultural icons — including former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, astronaut John Glenn, basketball coach Pat Summitt and rock legend Bob Dylan — with the Medal of Freedom at a White House ceremony Tuesday. The Medal of Freedom is the nation’s highest civilian honor. It’s presented to individuals who have made especially meritorious contributions to the national interests of the United States, to world peace or to other significant endeavors. (AP Photo/Chris Pizzello, File)

FILE – In this Feb. 6, 2015 file photo, Bob Dylan accepts the 2015 MusiCares Person of the Year award at the 2015 MusiCares Person of the Year show in Los Angeles. Dylan, the winner of this year’s Nobel Prize in literature declined the invitation to the Dec. 10 2016 prize ceremony and banquet, pleading other commitments. But the Nobel Foundation said Monday that Dylan has written a “speech of thanks” that will be read by a yet-to-be-decided person at the lavish banquet in Stockholm’s City Hall. (Photo by Vince Bucci/Invision/AP, File)

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.