How an FBI agent’s wild Vegas weekend stained a probe into NCAA basketball corruption

The FBI agents arrived in Las Vegas with $135,000 and a plan.

They took over a sprawling penthouse at the Cosmopolitan, filled the in-room safe with government cash and stocked the wet bar with alcohol. Hidden cameras — including one installed near a crystal-encrusted wall in the living room — recorded visitors.

In the heart of a city known for heists and hangovers, the four agents were running an undercover operation as part of their probe into college basketball corruption that investigators code-named Ballerz.

One of the agents was posing as a deep-pocketed businessman wanting to bribe coaches to persuade their players to retain a particular sports management company when they turned professional. He distributed more than $40,000 in cash to a procession of coaches invited to the penthouse. The sting concluded at a poolside cabana on a blistering afternoon in July 2017 with a final envelope of cash passed to one last coach.

After that transaction, the lead case agent, Scott Carpenter, joined the undercover operative and the two other agents in eating and drinking their way through the $1,500 food and beverage minimum to rent the cabana.

Carpenter had consumed nearly a fifth of vodka and at least six beers by the time he returned to the penthouse to shower and change clothes before a night out.

He grabbed $10,000 in undercover cash from the penthouse safe, then headed to a high-limit lounge at the casino next door. What happened next would ultimately stain the investigation like a cocktail spilled on a white tablecloth.

The high-profile FBI investigation focused on lesser-known coaches and middlemen.

The investigation was hailed as a watershed moment in men’s college basketball. But in an extensive reassessment, The Times examined thousands of pages of court testimony, intercepted phone calls, text messages, emails and performance reviews. The records provide a detailed look inside the high-profile investigation, led by a veteran FBI agent whose conduct on a vodka-soaked day in Las Vegas landed him on the wrong side of the law.

Ballerz was the top priority for the New York FBI’s public corruption squad for almost a year, according to Carpenter’s performance review in 2017, and included two undercover agents, operations in at least eight states, dozens of grand jury subpoenas and thousands of wiretapped phone calls.

The performance review and other court records offer new details about the lead case agent’s role and provide the most comprehensive account to date of the FBI’s handling of an investigation that, for all its hype, focused on lesser-known coaches and middlemen, most of them Black.

The weight of the federal government crashed down on college basketball at a livestreamed news conference in Manhattan when authorities unveiled the investigation in September 2017. The assistant director in charge of the New York FBI office warned potential cheaters that “we have your playbook.”

FBI agents, some with weapons drawn, had arrested 10 men, including assistant coaches from USC, Arizona, Auburn and Oklahoma State. Prosecutors alleged that the coaches took bribes and, in a related scheme, that Adidas representatives funneled money to lure players to colleges the company sponsored.

Major universities and shoe companies were deluged with subpoenas. Coaches retained attorneys, even if they hadn’t been charged, and rumors swirled about the government’s next target in its crusade to clean up the sport.

Carpenter’s performance review said the “takedown has already had a major national impact and … is likely to continue to have major impact.” Prosecutors characterized the effort in a court filing as “arguably the biggest and most significant federal investigation and prosecution of corruption in college athletics.”

But almost six years later, the operation that was supposed to expose college basketball’s “dark underbelly” didn’t transform the sport. No head coaches or administrators were charged. There wasn’t a public outcry.

Instead, the meandering government effort seemed at times like an investigation searching for a crime, marshaling vast resources to ultimately round up an assortment of low-level figures for alleged wrongdoing — particularly the coach bribery scheme — that people involved in the sport said wasn’t a common practice until the FBI started handing out envelopes of cash.

“This was a massive waste of time on everybody’s part,” said Jonathan Bradley Augustine, a former Florida youth basketball coach who was among those charged, though the charges were later dismissed. “It was a sexy case. This was big news. It was everywhere. … A lot of money wasted. A lot of people’s lives turned upside down.”

Scott Carpenter was the lead FBI agent on the undercover operation investigating corruption in men’s college basketball.

(Clay Rodery / For The Times)

“He had started to become reliant on vodka. Whenever I saw him, he either had a drink or I could smell it on his breath. I didn’t connect this to bigger mental health issues or the symptoms of PTSD that I learned about later.”

— Frank Carpenter

The saga started more than a decade ago with a Pittsburgh financial advisor and two ill-fated movie projects.

Louis Martin Blazer III, whose clients included professional athletes, had pumped money into two minor films. “A Resurrection,” which was about a youngster who thinks his brother is returning from the dead, earned just $10,730 at the box office. The other movie, “Mafia,” went straight to DVD with the tagline: “He crossed the wrong cop.”

To bankroll the investments along with funding a music management company, the Securities and Exchange Commission later alleged, Blazer misappropriated $2.3 million from five clients between 2010 and 2012, forging documents, making “Ponzi-like payments” to hide the theft, faking a client’s signature and lying to investigators.

Seeking leniency, Blazer met with federal prosecutors and the SEC in New York in June 2014. He came clean about the fraud — and volunteered details about an unrelated scheme prosecutors didn’t know about in which he had paid about two dozen college athletes to use his financial services firm when they turned professional. This could have rendered the players ineligible under NCAA rules and left their schools vulnerable to sanctions.

That fall, prosecutors put Blazer to work as a cooperating witness posing as a financial advisor trying to sign up college athletes as clients. He traveled the country to meet with agents, coaches, athletes and their family members, while recording conversations.

Blazer’s undercover operation had stalled by the time the FBI took over in November 2016, though the bureau saw “major unrealized potential” in the case, according to Carpenter’s performance review. Carpenter was transferred from the Eurasian organized crime squad to take over as the lead case agent on the basketball probe.

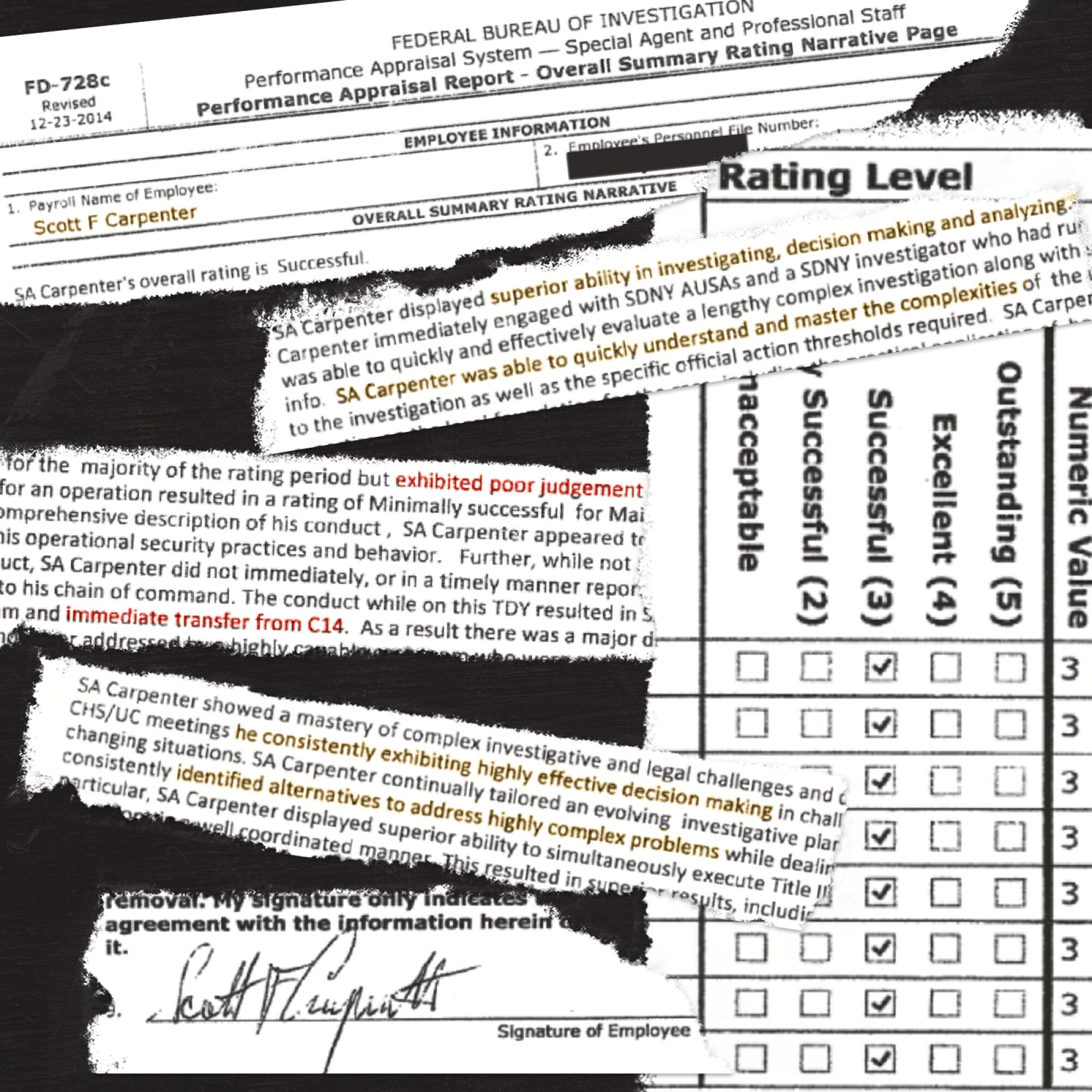

Scott Carpenter received a “successful” rating on his performance review and was mostly lauded for his work as the lead FBI agent on the investigation into college basketball corruption.

(Illustration by Los Angeles Times; Documents from court exhibits)

Raised in New Jersey as the son of a municipal judge and lawyer, Carpenter graduated from Wake Forest in the top of his ROTC class and served in Iraq as an officer with the 82nd Airborne. Carpenter’s annual officer evaluation in 2008 described his performance during 15 months in Baghdad as “absolutely phenomenal” with an “ability to turn chaos into order.” He left the Army that year as a captain, lived on the family’s sailboat and joined the FBI.

But signs of trouble began to emerge.

“He had started to become reliant on vodka,” his father, Frank Carpenter, would later write in a letter filed in court. “Whenever I saw him, he either had a drink or I could smell it on his breath. I still did not connect this to bigger mental health issues or the symptoms of PTSD that I learned about later.”

A court filing blamed his heavy drinking on the emotional toll from the lengthy deployment in Iraq and an improvised explosive device destroying the Humvee behind his vehicle.

At work, however, the complexities of the basketball probe appeared to be an ideal match for the skills of Scott Carpenter, who had worked on the high-profile investigation into global soccer corruption. His performance review said Blazer had previously been “unsuccessful in developing evidence,” but became “highly productive” under Carpenter’s direction.

Without Carpenter, the performance review said, “it is likely there would have been minimal if any investigative results.”

Jeff D’Angelo had money and wanted to invest it in a sports management company. The exact source of his wealth wasn’t clear. Real estate? Restaurants? Family? Wherever it came from, he talked like someone who orchestrated major deals.

The thirty-something slicked back his hair, liked to mention he served in the military and had the thick biceps of a workout fiend.

One person who met D’Angelo described him as a “mix between a hedge fund baby and Jersey Shore Italian.”

In fact, “D’Angelo” was a pseudonym. He was an undercover FBI agent. Carpenter served as D’Angelo’s handler. The lead case agent’s performance review lauded the work, saying that the undercover agent “had the resources and guidance to significantly expand this investigation” thanks to Carpenter.

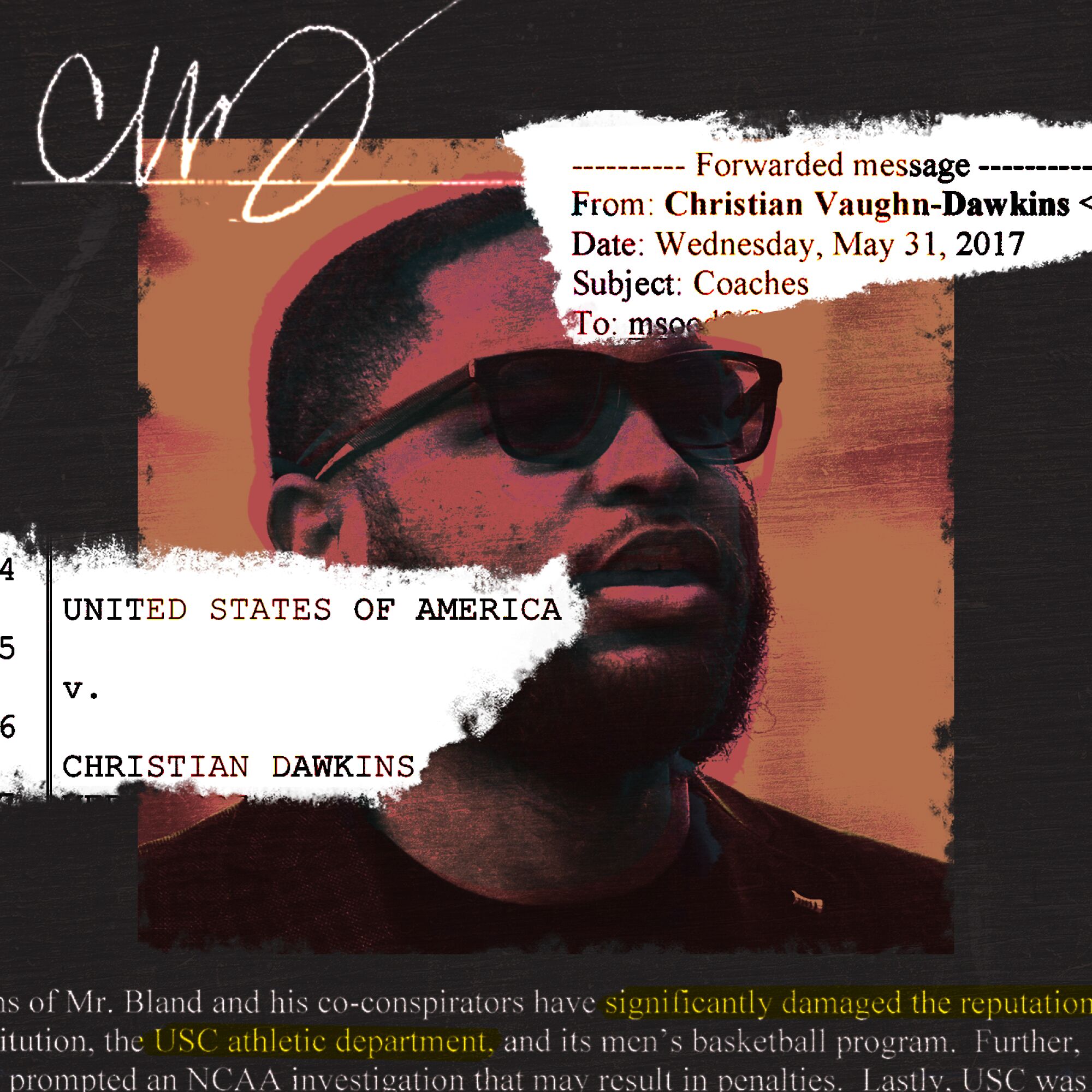

In mid-May 2017, D’Angelo was introduced at a Manhattan restaurant to Christian Dawkins, an ambitious 24-year-old attempting to start a sports management firm.

“If it makes sense … I’ll invest,” D’Angelo said. “I would put down some capital.”

Christian Dawkins launched his sports management company with the help of a $185,000 loan from an investor called Jeff D’Angelo, who was really an undercover FBI agent.

(Clay Rodery / For The Times)

Dawkins had grown up in Saginaw, Mich., the son of a basketball coach and middle school principal, and hoped to become a sports agent or college coach. As a teenager, he started a high school basketball scouting service called “Best of the Best” and peddled it to college coaches for $600 a year. He was a relentless self-promoter, mentioning himself in prospect updates, adding inches to his true height and listing himself among “standout campers” at a clinic run by his father.

After the 2009 death of his younger brother Dorian from a heart ailment while playing basketball, Dawkins helped start a youth travel team named Dorian’s Pride. He created an event company called Living Out Your Dreams — LOYD for short — named himself chief executive and organized basketball camps.

Just shy of 21, Dawkins joined a Cleveland financial advisory firm working with NBA players. He later moved to New Jersey-based ASM Sports, recruiting clients for the powerhouse sports agency.

Dawkins continued to pursue the goal of leading his own sports management company. He connected with Blazer through a bespoke suit maker with deep links to professional basketball. Dawkins outlined his ambition in an email to Blazer and another associate in April 2016 that, like secret recordings of their meetings, ended up in the hands of authorities: “I want to have my own support system, and I want to be able to facilitate things on my own, independent of ASM. … I just have to have the resources to continue.”

After the SEC accused Blazer of defrauding professional athletes in a news release the following month, Blazer testified that Dawkins “didn’t want to be around” him for almost a year.

In the meantime, Dawkins paid players and their families to retain ASM, according to his court testimony and exhibits, used two phones to stay in touch with some of the biggest names in the sport and relaxed in the green room at the NBA draft as players waited to be selected. When an associate joked in a text message that Dawkins seemed to be everywhere, he responded with apparent pride, “But never seen.”

On a windy afternoon in June 2017, Dawkins boarded a large yacht moored at the North Cove Marina in Manhattan’s Battery Park.

He expected to finalize the launch of his sports management company. In reality, the gathering was a setup. Everything was recorded. Among those in attendance were Blazer and D’Angelo, who introduced Dawkins to a wealthy friend named Jill Bailey. She was another undercover FBI agent.

In the agreement signed that day, D’Angelo pledged to lend $185,000 to the company in exchange for a minority stake. Dawkins got 50% of the firm called Loyd Inc. and would be president. The company didn’t have a licensed NBA player agent, formal structure or even an office. D’Angelo — whose name was misspelled in the contract — handed out $25,000 in cash for the company’s start-up expenses.

In June 2017, Christian Dawkins, second from right with arms folded, boarded a two-story yacht in Manhattan expecting to finalize the launch of his sports management company. In reality, the gathering was a setup. (U.S. Justice Department)

D’Angelo wanted to pay college coaches to direct their players to use the new company when they became professionals, saying if the firm had “X amount of coaches that are on board with our business plan … that’s just that many more kids we’re gonna have access to essentially every month.” Dawkins was skeptical. If the investor insisted on paying coaches, he argued, only “elite level dudes” should get money. Still, Dawkins offered to introduce D’Angelo to several coaches the following month when they flooded Las Vegas for a huge youth basketball tournament.

In the days and weeks that followed, Dawkins complained to associates in recorded conversations that bribing coaches was nonsensical. The best players usually spent less than a year on campus before leaving and had limited time with coaches. Parents, close relatives, youth coaches or middlemen, like Dawkins, exerted the real influence in the daily lives of many top-level players.

A system built around the NCAA’s ban on paying players and their families was lucrative for everyone but the people on the court. The NCAA brought in $761 million from the March Madness tournament in 2017. Multinational shoe companies paid universities to wear their gear. Top head coaches earned $4 million or more a year. It all helped to nurture a thriving underground economy with bidding wars for top players to attend universities, retain agents, sign with financial advisors.

The distribution of aboveboard money reflected only part of the power imbalance. While 81% of Division I athletic directors and 70% of men’s basketball head coaches were white in 2017, 56% of their players were Black. If the 47% of assistant coaches who were Black had a prayer of landing a head coaching job — or remaining employed — they needed to land top-level players.

The four college assistant coaches charged in Ballerz — and eight of the 10 initial defendants, including Dawkins — are Black. The four Black coaches all worked for white head coaches.

“When you’re a Black assistant coach, man, you’ve got the world on your shoulders,” said Merl Code, a former college basketball player who worked for Adidas and Nike and became a target of the sting. “If you don’t get kids, then you don’t keep your job. But if you don’t do what’s necessary to get kids, you’re not going to be successful, and what’s necessary to get the kids is to help the family.”

“We’re just going to take these fools’ money.”

— Merl Code

In conversations with D’Angelo, who is white, Dawkins maintained that paying coaches to influence their athletes wasn’t “the end-all be-all.”

“I’m more powerful,” Dawkins told him, “than any coach you’re going to meet.”

The dispute came to a head during another recorded phone call a few weeks after the yacht meeting.

“If you just want to be Santa Claus and just give people money, well f—, let’s just take that money and just go to the strip club and just buy hookers,” Dawkins told D’Angelo. “But just to pay guys just for the sake of paying a guy just because he’s at a school, that doesn’t make common sense to me.”

D’Angelo wasn’t swayed. The investigation was built around ensnaring coaches.

“Here, here, here, here’s the model,” D’Angelo stammered.

He had the money, he said. They would pay coaches.

“I respect that … you don’t think that’s the best approach, but that’s what I’m doing,” D’Angelo said in the call. “That’s just what it’s going to be.”

Afterward, Dawkins vented to Code in a wiretapped phone call that throwing cash at a slew of coaches meant spending lots of money for no discernible purpose.

“We’re just going to take these fools’ money,” Code said.

“Exactly,” Dawkins replied. “Because it doesn’t make sense. … I’ve tried to explain to them multiple f— times. This is not the way you wanna go.”

Christian Dawkins set up a sports management company and boasted to potential investors of his relationships with prominent college basketball coaches. In reality, the biggest investor in his firm was an undercover FBI agent.

(Illustration by Los Angeles Times; Photo by Seth Wenig / Associated Press; Documents from court exhibits)

During a call with an associate in early July, Dawkins wondered aloud if he should find someone to pay back the money D’Angelo had invested in Loyd and end their relationship. The investor’s odd requests, like wanting to meet players and their parents, unnerved Dawkins. He wondered why D’Angelo cared so much.

“People are gonna think that honestly they’re being set up,” Dawkins said in the recorded call.

But he still wanted D’Angelo’s cash. A few days after the call, Dawkins and Code faced a problem. Prosecutors alleged they had agreed to help funnel cash from an Adidas company employee to the family of a touted high school prospect who had agreed to play for an Adidas-sponsored university. An installment had been delayed. D’Angelo agreed to provide a loan of $25,000.

The payment came at a critical point in the investigation, according to Carpenter’s performance review. He pushed for it to preserve D’Angelo’s “bona fides as a high roller” and “set in motion events which would widely expand the case from addressing bribery by NCAA coaches to incorporating the illegal conduct of officials at a major international sportswear company.”

As the Las Vegas trip approached, Code and Dawkins brainstormed which coaches could meet D’Angelo, but Code’s unease about the investor was growing.

“I’m looking up Jeff D’Angelo and I can’t find nothing on him,” Code told Dawkins in a phone call on July 24, 2017, “and that s— is really concerning to me.”

Carpenter flew to Las Vegas on July 27, 2017, accompanied by a supervisor, junior agent and the undercover operative — and having “serious misgivings” about whether he had enough personnel to run the operation.

Over three days, D’Angelo, Dawkins and Blazer met with 11 coaches — 10 college assistants and one youth coach, all in town for the youth tournament — at the Cosmopolitan. The trendy hotel that advertised “Just the right amount of wrong” seemed to be the ideal setting.

Tony Bland, in a white shirt, was among the college coaches who met with Jeff D’Angelo and Christian Dawkins in the penthouse suite at the Cosmopolitan. (U.S. Justice Department)

Augustine, the Florida youth coach, recalled that Blazer fixed him a vodka water when he stopped by the penthouse on the first night. The opulent surroundings staggered the coach. His players were jammed into rooms at a budget-friendly hotel. The penthouse appeared to be a different world. Black marble and dark wood. Enough seating — bar stools, couches, easy chairs — for a full team. Master bathrooms that rivaled the size of some hotel rooms. A huge balcony. Quirky art around every corner, like the enormous photo of a golden-hued woman dancing underwater in a swirl of purple fabric.

Augustine received an envelope from D’Angelo stuffed with $12,700, according to the complaint. The next day, Augustine said he deposited much of the cash at a nearby bank and, since his players had flown to Las Vegas on one-way tickets, used some of the windfall to pay their way home. Augustine said he used the remainder to pay down debt he had accumulated while running the team. (He was later charged with four felonies, but all counts were dropped.)

The hidden agendas at play in the penthouse seemed tailor-made for Sin City. D’Angelo distributed envelopes of bribe money as cameras recorded each transaction. But Dawkins later claimed he had arranged for three of the coaches to give him their would-be bribe money so he could run the company his way.

Dawkins pleaded with Preston Murphy, then a Creighton University assistant coach and longtime family friend, to meet with D’Angelo in the penthouse, saying he would be forced to move in with his parents if the financial backers didn’t support him, according to Murphy’s attorney.

“I needed him to basically help me, you know, continue to get funding,” Dawkins testified.

Former Creighton assistant coach Preston Murphy, left, was caught up in the investigation but was never charged. Former USC assistant coach Tony Bland, right, pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit bribery and was sentenced to probation for admitting to receiving $4,100.

(Associated Press)

NCAA investigators said in reports that Murphy and TCU assistant coach Corey Barker knew before their meetings in the penthouse on July 28 that they would be paid and had agreed to give all of the money to Dawkins. Prosecutors alleged Murphy and Barker each received $6,000 from D’Angelo. Murphy handed the cash over to Dawkins in a bathroom off the main casino floor, while Barker did the same near the hotel’s valet parking stand, according to accounts they gave to the NCAA. The same day, Dawkins deposited $5,000 in cash into the Loyd bank account. (Neither Barker nor Murphy was charged.)

Shortly after midnight on July 29, Tony Bland, a USC assistant coach, sank into a couch in the penthouse. He had arrived from L.A. that afternoon and looked tired. The conversation sounded like the others — boasts about influence over college players, banter about prospects with a shot at the NBA.

“I have some guys that I bring in that I can just say, this is what you’re f— doing,” Bland said. “And there’s other guys who we’ll have to work a little harder for, but we’ll still have a heavy influence on what they do.”

Hidden-camera footage shows Dawkins, not Bland, pick up an envelope of cash from the coffee table. The federal criminal complaint alleged Bland — making more than $300,000 a year at USC — got the $13,000 in the envelope. But bank records show Dawkins deposited $8,900 at an ATM later that day. Bland eventually pleaded guilty to receiving $4,100, the difference between the $13,000 and the deposit.

Dawkins testified that the actual amount Bland received was less because he only gave Bland “between $1,000 and $2,000” to spend at a bachelor party that night.

For the final undercover meeting, the FBI team had rented a poolside cabana at the Cosmopolitan. Afterwards, the agents decided to use the cabana for themselves when they learned the $1,500 they paid for the space was actually a food and beverage minimum, according to a court filing.

“Despite the obstacles, all of the undercover meetings were very successful,” Carpenter’s attorney wrote in a court filing. “At the same time, there is no doubt that the intensity, anxiety, elation and exhaustion of the weekend’s activities left Mr. Carpenter in an even more precarious position.”

After showering and changing clothes in the penthouse following the alcohol-filled afternoon at the cabana, the four FBI agents walked next door to the Bellagio Hotel and Casino and ended up at a high-limit lounge.

Carpenter bought $10,000 in gambling chips with the government cash he had taken from the penthouse safe and started playing blackjack. The three other agents — including Carpenter’s supervisor — watched him gamble from an adjacent bar and took turns visiting, according to court testimony and a filing by his attorney, as Carpenter gulped free drinks and lost.

“They at least had to have a decent idea it was undercover FBI money and nobody took the keys to the car,” Carpenter’s attorney Paul Fishman said in court.

The lead FBI agent lost $13,500 in government cash while gambling in Las Vegas.

(Clay Rodery / For The Times)

Carpenter churned through the $10,000, then pressed the undercover agent — D’Angelo — for additional government cash. He handed it over.

According to a court filing, Carpenter played for two to three hours, placed an average bet of $721 and, by the time he walked away, had lost $13,500.

As the alcohol wore off in the early hours of July 30, Carpenter paced around the penthouse. According to a document read in court, one of the agents told an investigator that Carpenter was brainstorming how to make it right and asked if they could say the gambling was part of the operation. The agent refused.

The undercover agent alleged that the four agents met early that morning and “there was a discussion … to just take care of it,” Assistant U.S. Atty. Daniel Schiess said in court. The supervisor and junior agent, Schiess said, “hotly contest” that such a meeting occurred.

In a court filing, Carpenter’s attorney wrote that his client “vehemently disagrees” that he “intended in any way to conceal his conduct or evade responsibility.”

After returning to New York and taking a scheduled day off, Schiess said, Carpenter met with his supervisor about the missing money and, afterward, told the undercover agent and the junior agent he was going to try to pay it back and asked if they could split the cost. The other agents and Carpenter’s supervisor who was in Las Vegas aren’t identified in court records.

“Carpenter appeared to have displayed poor judgment in some of his operational security practices and behavior …”

— FBI performance review

Two days later, Carpenter was transferred from the public corruption squad and college basketball investigation. He checked into an inpatient alcohol treatment program the following week, according to a court filing.

D’Angelo was also pulled from the case. He told Dawkins in a phone call Aug. 8 that he was traveling to care for his ailing mother in Italy.

Carpenter’s performance review from 2017 devoted one paragraph to the incident: “Carpenter appeared to have displayed poor judgment in some of his operational security practices and behavior … (he) did not immediately or in a timely manner report events constituting potential misuse of funds to his chain of command.”

Nevertheless, the review rated Carpenter’s overall performance as “successful.”

Heavy footsteps woke Bland almost two months later in Tampa, Fla., early on the morning of Sept. 26. Someone pounded on the door of his hotel room. The USC assistant coach had stayed out late the night before to celebrate the commitment of a recruit to play for the school. Bland got out of bed and opened the door. A team of FBI agents with weapons drawn burst into the room. One of them twisted his right arm behind his back — the arm still doesn’t feel right today, Bland said — and shoved him against a wall. Bland told them they had the wrong man.

Around the same time, Code answered the door at his home in Greer, S.C., in his underwear. He counted at least 20 FBI agents, some brandishing pistols and assault-style rifles, and 15 vehicles lined up on his block.

Four NCAA assistant coaches were charged after the investigation.

(Clay Rodery / For The Times)

Augustine, the Florida youth coach, had planned to meet Dawkins that morning at a New York hotel. He checked his phone on the walk over and found scores of tweets mentioning him, then scrolled through the criminal complaint against him while standing in Times Square. He thought it was some kind of elaborate, twisted joke. Then the FBI called and, a half-hour later, arrested him.

Similar scenes played out across the country. At the news conference in Manhattan the same day, the acting U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York alleged the defendants had circled “blue chip prospects like coyotes.”

The four college assistant coaches who were charged lost their jobs. Augustine resigned from the youth team and swept floors in his father-in-law’s warehouse to make ends meet.

Carpenter kept his badge, service weapon and security clearance after returning from the alcohol treatment program. But he was exiled to a facilities squad to help manage a remodeling project at the FBI office in New York.

Judges in the two Ballerz trials barred defense attorneys from questioning witnesses about alleged misconduct by agents during the Las Vegas trip. One of the judges ruled that it “did not occur while the agents were conducting investigative activities” and was “irrelevant to this case.”

Though Carpenter and the agents posing as D’Angelo and Bailey were subpoenaed, they didn’t testify. In the first trial, Code, Dawkins and a former Adidas employee were convicted of using payments to steer players to attend three universities sponsored by the sportswear giant. Then Code and Dawkins were found guilty during the second trial, which focused on the alleged scheme to bribe coaches to persuade their players to use the sports management company that the undercover agent had helped finance.

The investigation led to 10 men being convicted of felonies at trial or by taking plea deals. Five were sentenced to prison. Dawkins got the longest combined term — 18 months and a day.

After Dawkins’ sentencing, prosecutors released a statement warning that the outcome “should make crystal clear to other members of the basketball underground exposed during the various prosecutions brought by this Office that bribery is still a crime, even if the recipient is a college basketball coach, and one that will result in [a] term of incarceration.”

Merl Code, left, a former college basketball player who worked for Adidas and Nike and became a target of the FBI’s investigation, served five months and nine days in prison. Book Richardson, right, a former University of Arizona assistant men’s basketball coach, was sentenced to three months.

(Photos by Bebeto Matthews and Larry Neumeister / Associated Press)

Bland had been placed on administrative leave by USC after being arrested, then was terminated about four months later. He pleaded guilty in 2019 to a felony, conspiracy to commit bribery, and was sentenced to probation for admitting to receiving $4,100. Prosecutors argued that USC faced “significant potential penalties from the NCAA” because of his conduct, echoing claims they made in sentencing memorandums for other defendants.

The cases were built around the theory that universities were the victims. Prosecutors argued the schools had been deceived into issuing scholarships to athletes who would be ineligible under NCAA rules barring payments to players or their families. They also argued the schools had been exposed to penalties from the organization for other rule-breaking, including a prohibition on coaches and other employees benefiting from introducing athletes to agents, financial advisors or their representatives.

In a victim impact statement filed in court, USC said the school, “its student athletes, and college athletics as a whole have suffered greatly because of what Mr. Bland and his co-conspirators did.” The school’s statement came at a time when USC was already reeling from its involvement in the Varsity Blues college admissions scandal and allegations that a campus gynecologist had sexually abused hundreds of students.

In the years since Ballerz became public, several universities have been sanctioned by the NCAA in connection with the investigation, but the penalties have largely been lighter than the “significant” punishments prosecutors warned about in sentencing memorandums for the defendants. USC, for example, received two years of probation and was fined $5,000 plus 1% of the men’s basketball budget.

More significantly, some long-standing NCAA rules have shifted. College athletes can now profit from their name, image and likeness, known as NIL. Last year, Adidas unveiled a nationwide NIL program for athletes at schools sponsored by the sportswear giant.

Jay Bilas, a former Duke basketball player who is an attorney and ESPN television analyst, called the investigation a waste of time and resources.

“It seemed like bringing in the National Guard to deal with jaywalkers,” Bilas said. “It damaged people’s lives over nothing. … At the end of the day, all it did is make a lot of noise without a lot of result.”

The FBI declined to comment for this story.

Blazer, who originally told prosecutors he could expose college sports corruption, pleaded guilty to five charges — for misappropriating money from five clients and paying college football players to retain his financial advisory firm — and was sentenced to one year of probation in February 2020. He admitted misappropriating $2.35 million from clients — much more than all the bribes combined in Ballerz.

Today, Bland coaches basketball at St. Bernard High School in Playa del Rey. He said he loves working with young players, but is eager to return to coaching in college when a three-year penalty imposed by the NCAA as punishment for the bribe expires in April 2024.

He struggles to sleep in hotel rooms, his heart pounds if there’s an unexpected noise in a hallway, and he can’t get past the allegations against the lead case agent in Las Vegas.

“It’s like, OK, [the FBI] can mess up … and still run you over,” Bland said. “It doesn’t even matter.”

Code wrote a book about college basketball’s underbelly called “Black Market” before serving five months and nine days in prison.

“If anyone thinks that there is such a thing as a clean big-time program, they need to wake up and smell the donkey s—,” he wrote in the book.

Suicide prevention and crisis counseling resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, seek help from a professional and call 9-8-8. The United States’ first nationwide three-digit mental health crisis hotline 988 will connect callers with trained mental health counselors. Text “HOME” to 741741 in the U.S. and Canada to reach the Crisis Text Line.

Book Richardson, a former University of Arizona assistant coach, was sentenced to three months in prison in the case. He now makes $3,000 a month working with youth basketball players in New York. He has kidney disease and sometimes struggles with the person he sees in the mirror. He said he contemplated suicide on two occasions in the years following his arrest — once when he put a pistol in his mouth but was interrupted by a phone call from a friend.

“Your mind starts messing with you, man,” Richardson said. “‘Maybe I am the scum of the earth. Maybe I am the worst coach ever. I threw my life away for $20,000. I should be dead.’”

Carpenter was transferred to a counterintelligence squad in October 2020, the same month he and his wife bought a home listed at 3,200 square feet with a swimming pool in suburban New Jersey. In a letter from his wife later filed in court, she wrote that the couple had assumed Carpenter’s construction assignment had been the extent of his punishment.

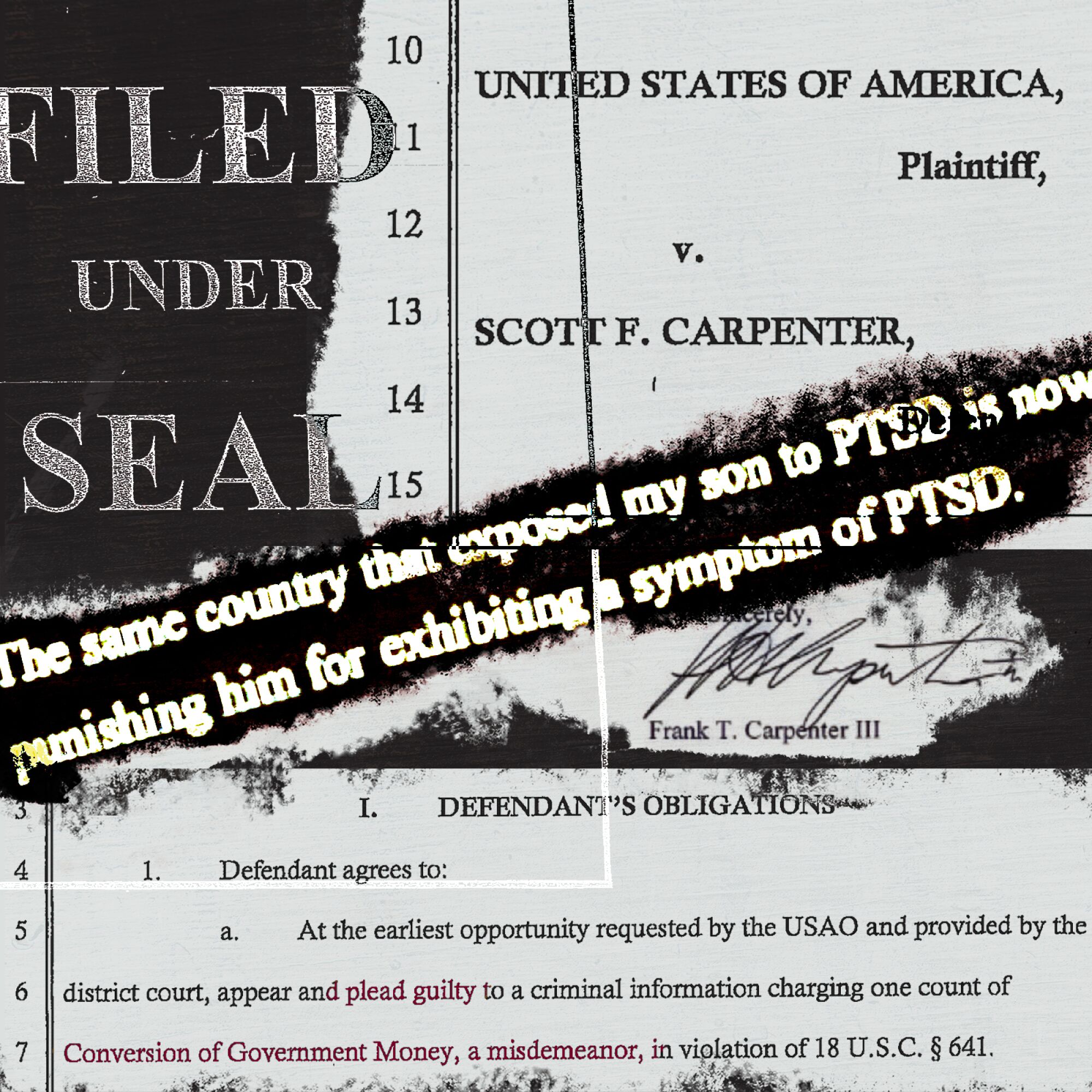

On Dec. 13, 2021, the Supreme Court denied the final appeal related to the Ballerz investigation. Four days later, Carpenter signed an agreement to plead guilty to a misdemeanor charge of conversion of government money for gambling away the $13,500. The agreement and his presentencing memo detail the events surrounding his misconduct in Las Vegas. The FBI suspended Carpenter after he pleaded guilty, then terminated him in May.

In the criminal case against Scott Carpenter, his father wrote a letter to the judge asking for leniency, saying his son suffered from PTSD symptoms after his military service in Iraq.

(Illustration by Los Angeles Times; Documents from court exhibits)

Steve Haney, the attorney for Dawkins, learned about Carpenter’s plea in a news release and moved for a new trial for his client. But a judge rejected the motion, finding the “misconduct did not concern the defendants.”

Last August, Carpenter returned to Las Vegas to be sentenced. He was contrite during brief remarks at the hearing: “Five years ago, I made a terrible and stupid mistake. … While there isn’t an excuse for what I did, there’s an explanation: The combination of job stress, alcohol and lingering issues from my military service.”

Fishman, Carpenter’s attorney, characterized the blackjack episode as an isolated error in an otherwise exemplary life. He told U.S. District Judge Gloria M. Navarro that Carpenter returned from Iraq “not quite right” and has been “hellbent” on righting his wrong. The judge interjected during Fishman’s argument that his client had not been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Navarro told Carpenter he had “already received a lot of lenience.” He wasn’t immediately fired, hadn’t been arrested, kept being paid — he and his wife reported an income of $411,000 on their 2020 tax return, the judge said — and wasn’t even on pretrial supervision, something the judge couldn’t recall for a defendant in her courtroom. She sentenced him to three months of home confinement and ordered him to repay the government money. Carpenter declined to comment.

The status of the three FBI agents who accompanied him to Las Vegas is unclear.

Former FBI Special Agent Scott Carpenter, right, leaves a federal courthouse in Las Vegas in August after being sentenced for gambling away $13,500 in government money.

(Bizuayehu Tesfaye / Las Vegas Review-Journal)

The Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General, which investigated the Las Vegas misconduct along with the U.S. attorney’s office in Nevada, has declined to comment on the case and refused to turn over any records in response to Freedom of Information Act requests, saying to do so could interfere with enforcement proceedings.

Meanwhile, Dawkins is serving his sentence at a low-security federal prison in North Carolina and is scheduled for release in May.

Before reporting to prison, Dawkins founded another company. Unlike the ill-fated venture backed by undercover FBI agents, Par-Lay Sports and Entertainment has a veteran management team that includes his defense attorney. A teenage phenom named Scoot Henderson, projected to be the second overall pick in June’s NBA draft, is one of the firm’s clients.

The draft will be held in Brooklyn, N.Y., some three miles from the courthouse where Dawkins’ life was upended and the room where the FBI boasted they had the “playbook” for college basketball corruption. Dawkins, his attorney said, is expected to attend.

For all the latest Sports News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.