High-Speed Rail to Singapore back on the table? UMNO leader demands visionary planning

Disclaimer: The following opinion piece represents author’s personal views.

As the new Malaysian government is reconsidering running the ill-fated high-speed rail (HSR) line from Kuala Lumpur (KL) with a terminus in Johor, Mohamed Khaled, UMNO VP and former menteri besar of Johor, has taken another opportunity to lambaste the lack of courage of the federal authorities for not extending the line to Singapore.

When Malaysia built the Kuala Lumpur International Airport, Putrajaya and the North-South Expressway, we were not a rich country then. But we still did it with economic planners who had vision and were ahead of their time.

The country needs economic planners who can unearth Malaysia’s true strength and our economic plans can no longer be inward looking. I hope that the Prime Minister will not repeat the mistakes made by Pakatan Harapan and Perikatan Nasional. I am confident that he wants to revive the country’s economy through competitive and fruitful projects. Otherwise, Malaysia will become a third-world country that is only slightly better than other third-world countries.

– Mohamed Khaled, VP of UMNO, October 23, 2021

His observations are spot on, but can they garner broader support?

A wasted opportunity

Back in 2018, I celebrated the ousting of Barisan Nasional (BN) with my urban Malaysian friends, hoping that the new Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition — even under strong influence of Mahathir — would help to put Malaysia on a better track.

In perspective, however, it has turned out that Najib — however flawed he may have been — was still the best prime minister that the country has had in its modern history. For all his sins, he understood the value of infrastructural projects to the nation, particularly one that is lagging so badly in terms of public transit.

It was his initiative to build the first proper — and badly needed — MRT lines in KL, connect the capital to the East Coast via ECRL and link KL and Singapore via HSR, which would allow for an effortless and swift commute that would take as little as 90 minutes, bringing both metropolises closer than ever.

Sadly, even if we assume that the government that took over in 2018 was less corrupt than previous administrations, it was not necessarily more competent — and even subsequent Perikatan Nasional cabinet followed the path of confrontation rather than cooperation with Malaysia’s diminutive neighbour, what ultimately derailed the HSR project completely in December 2020.

Instead of enjoying blisteringly quick commute just five years from now, by the end of 2026 (as per original plan) it may not happen for decades (or ever) and thousands of commuters will continue wasting four to six hours by bus or plane (if we consider the necessary wait, security checks and commute time to and from the airports).

Good for Singapore, great for Malaysia

Given that the two nations are so intertwined through economic, political and even familial relations of their citizens, creating ever closer ties to facilitate cross-border travel is a no-brainer (despite sharing border with Thailand, Thai population centers are very far away from Malaysia and Bangkok itself is 1,500 km from KL).

And considering just how bad public transit infrastructure is in Malaysia (reduced to an ancient, unreliable and slow narrow gauge and forever delayed trains) then creating a fast, modern connection linking its major population centers along the western coast of the peninsula would not only have reduced the strain on the clogged up highway network, but also allow for much better (and profitable) utilisation of land along the line.

Back in January 2021, after the project was officially called off, Mohamed Khaled reminded the government that by a simulation done by the Japanese Institute of Developing Economies, the HSR was supposed to contribute US$1.589 billion (RM6.38 billion) to the Malaysian economy each year – 2.5 times more than to Singapore.

Malaysia has now lost a golden opportunity to strengthen our relations with two major metropolis cities, which are among the main economic engines of Southeast Asia.

– Mohamed Khaled, January 5, 2021

All is not lost yet?

With the collapse of Muhyiddin Yassin’s cabinet and return to power by BN under Ismail Sabri, the HSR project has received a slight, but noticeable boost.

Last month, ex-PM Najib Razak himself appealed to the new government in Dewan Rakyat during the debate over 12th Malaysia Plan (for the years 2021 to 2025), to reconsider the rail project to Singapore:

The vision, mission and projects such as the HSR which will connect two of ASEAN’s largest economies, need to resume according to the original concept and planning. (This is) in addition to giving a new life to the southern corridor of the peninsula such as Iskandar Malaysia, Batu Pahat, Muar, Melaka and Seremban.

Reviving the HSR project according to its original plan can also revive the Bandar Malaysia project, worth RM140 billion in terms of gross development value.

– Najib Razak, September 28, 2021

High-speed rail corridor has not been officially abandoned and the MyHSR corporation continues to function, but it’s clear that any attempts at ending the line in Johor will not produce the desired economic benefits.

Excluding Singapore from the equation — perhaps in the hopes that the city will concede to it once the line is nearly completed and under Malaysian control — would be an economically risky gamble that may end up creating another white elephant.

Again, it seems that Najib understood that it makes sense to concede something to Singapore for the sake of good relations and partnership that are necessary for swift and painless execution. That’s how it could have proceeded so quickly and begin yielding benefits to both economies as early as 2026.

It’s good to see that the project is still on the agenda in the echelons of Malaysian politics, but it’s unlikely that any breakthrough decisions can be made before the next Malaysian General Election in 2023.

The current ruling coalition is still a rather weak patchwork of BN and former opposition parties, loosely supporting a compromise candidate. It is nothing like the dominance that Barisan Nasional had enjoyed for about 60 years until its defeat in 2018.

Dealing with the fallout of COVID-19 pandemic is currently the priority of governments all over the world, and Malaysia is no exception. Hugely expensive and potentially contentious projects will not reappear in the spotlight until the new parliamentary order is established in 2023.

Singapore in a bind

Given the lack of space in the city-state, Singapore will likely be developing its thus far reserved plots of land quite carefully, in case the train link is revived.

In fact, in a long-term perspective, it would be absolutely mind-boggling that it is not connected to KL via a high-speed train. All you have to do to understand it is just glance at a map.

However, lack of commitment from the Malaysian government creates problems for Singapore which cannot itself commit to how the affected areas of the city are going to look like or be developed.

After all, the big promise for Jurong was that the town would benefit greatly from the HSR terminus, boosting attractiveness of housing and office spaces there. But with the station gone, everything else is affected negatively.

Should the authorities draw up a completely new plan for the area? Should they keep enough land in reserve, in case the project is back sooner than anybody expects?

It’s a tough call and a major annoyance, since logically speaking, both countries should treat HSR as a priority. But until Malaysia can commit, there’s no saying whether it can happen in 10, 50 or 100 years down the road. Singapore can’t just fence off land (that it has so little of) for a project that may not happen for decades.

GE 2023 will set the direction

It seems that we’ll have to wait at least two years for an answer, though.

If BN reclaims parliamentary majority in 2023, it’s quite likely that HSR will be back on the table, perhaps along the lines of the agreement concluded with Singapore in 2016. It would certainly expedite the process — assuming that the city-state does not begin any developments on the plots originally reserved for the line (what would force track realignment and further delays).

In such a case, the entire railway could be completed by mid-2030s while funding — despite the current economic woes — might not be such a serious problem if the government heeds Najib’s suggestion to hand the project to national funds: EPF and PNB, which collectively manage over RM1 trillion in assets (the HSR line was projected to cost between RM60 and RM110 billion).

Former PM pointed to the recent successful cooperation between both companies in acquisition and redevelopment of iconic Battersea Power Station in the heart of London — into a multi-use commercial and residential area — as an example of their competent handling of major construction projects.

Civilisational leap

Whoever wins in 2023, hopefully they will embrace a more modern way of thinking and consider the benefits of the HSR to Malaysia itself. It presents an amazing opportunity for the country to leap ahead in civilisational terms.

Most nations, even highly developed ones, typically have to make do with existing infrastructure, progressively updated over time (as it would be expensive or often even impossible to construct a dedicated high-speed link over existing tracks).

But Malaysian railways have been neglected for so long (and are almost exclusively narrow gauge) that the country is not burdened by any existing standard gauge network and can leap ahead to construct completely new infrastructure capable of running trains at 300kph or more.

And because of the shape of the peninsular Malaysia and the fact that all major cities are located along a single north-south axis, most of the country’s population would be located in proximity to it (assuming a possible future extension north to Penang), cutting travel time for most Malaysians by huge margins.

Few countries enjoy such advantageous demographic and geographic conditions, which would allow them to achieve so much with such a (relatively) limited investment.

Simply looking at the map of the peninsula, it is clear that a north-south railway link is — rationally speaking — inevitable. It’s the most obvious investment that both Malaysia and Singapore can engage in.

Why keep delaying it? Why keep wasting time and money that it would have clearly brought to both economies, to bilateral travel, trade, business, construction, environment and comfort of life of millions of people (predominantly Malaysians)?

I really hope that, once the political situation clears by 2023, HSR is going to be revived and we will ultimately be able to chant (non-ironically) “Malaysia boleh!”, after all.

Get $20 off your order on VP Label when you checkout with Pace and the code PACEVP20 (min spend $80). Discover and shop exciting homegrown brands now:

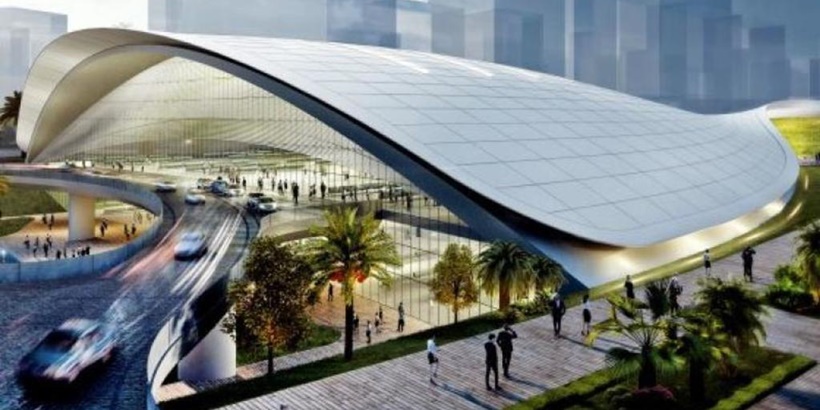

Featured Image Credit: Depositphotos

For all the latest Life Style News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.