From ‘women’s pages’ to front lines: Tracking women journalists’ (unfinished) progress

Review

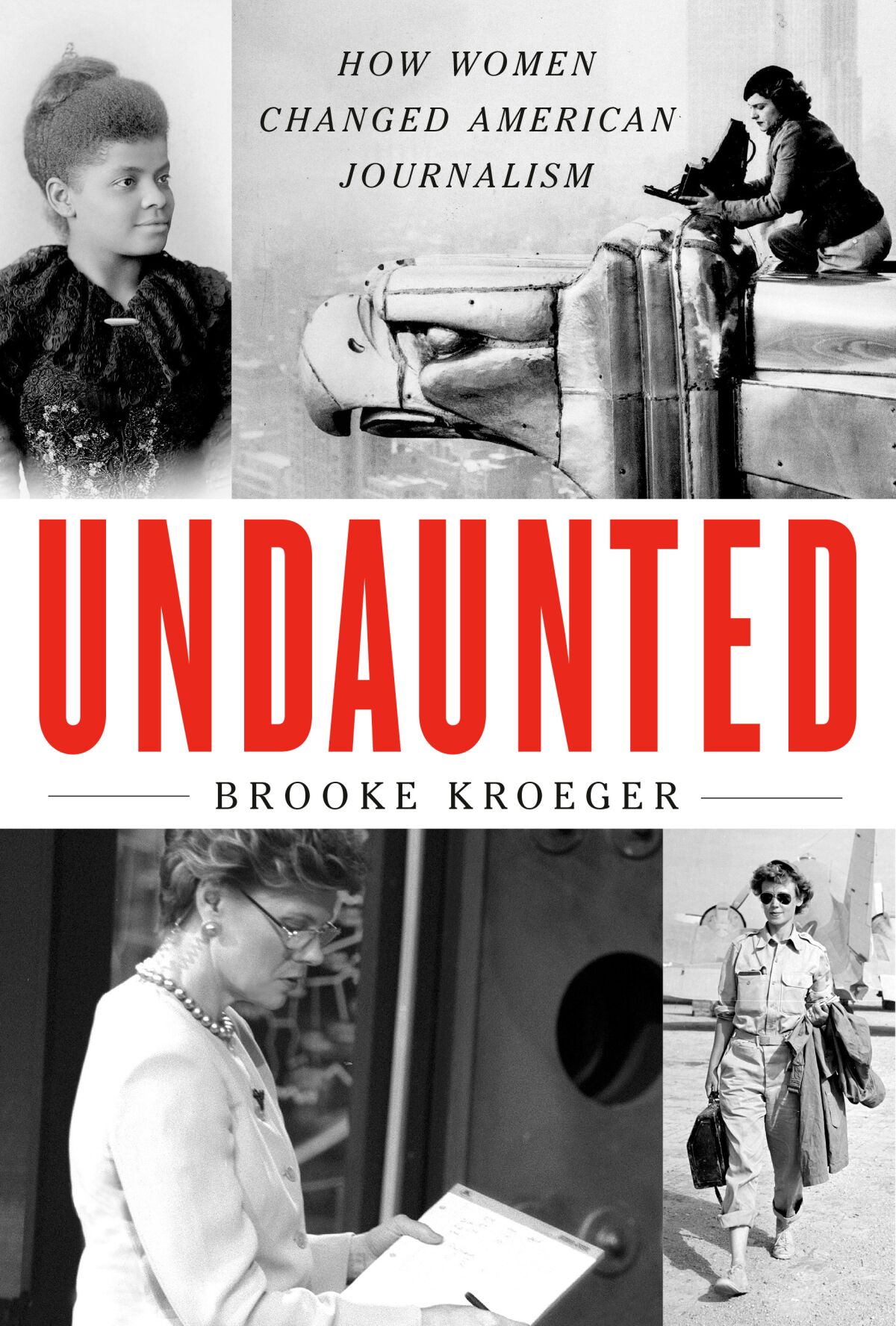

Undaunted: How Women Changed American Journalism

By Brooke Kroeger

Knopf: 592 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Back in February, Wall Street Journal reporter Sabrina Siddiqui got a plum assignment. She was tapped to be one of two journalists accompanying President Biden on a secret visit to Kyiv. But she had a logistical challenge: As a new mother, Siddiqui was still nursing and would need access to electricity and refrigeration throughout the journey to keep pumping and storing breast milk.

Neither was guaranteed to be available on a train trip in a war zone. But rather than disqualifying Siddiqui from covering the historic moment, the White House helped her manage the situation.

That kind of accommodation for women’s needs was unthinkable when I started out as a Washington reporter in 1979. Men still dominated prestige beats like the White House. The profession’s elite Gridiron Club had just admitted its first female members in 1975. As recently as 1995, when I joined the Los Angeles Times’ Washington bureau, only seven of the 35 staff reporters were women.

I retired from full-time political reporting in 2021 and have thought a lot about how much journalism — and women’s place in it — has changed over four decades. Brooke Kroeger, professor emerita at New York University, reaches even farther back for a broad look at women’s evolving role in her new book, “Undaunted: How Women Changed American Journalism.” As the U.S. reels from the abrupt rollback of abortion rights, this book is a timely reminder that while women have come a long way in journalism, their gains can’t be taken for granted.

Brooke Kroeger, who has previously written bioraphies of Nelly Bly and Fannie Hurst, takes on a broader scope in “Undaunted: How Women Changed American Journalism.”

(Jenn Heffner / East 27 Creative)

“Undaunted” starts with pioneering female journalists of the 19th century such as Margaret Fuller and Ida B. Wells and marches through to the present. Kroeger is well equipped to take us through generations of determined, tenacious women: She is a former reporter and editor for UPI and Newsday, a scholar and author of several books, including biographies of reporter Nellie Bly and writer Fannie Hurst.

Nevertheless, the scope and style of “Undaunted” make for some unwieldy reading. It is an exhaustive catalog of female journalists — some famous, many lesser known — and the recap of their accomplishments can be plodding at times.

Most compelling are the examples of how women made a distinctive mark on journalism. Bly, with her crusading first-person exposés, was the founding mother of undercover investigative reporting. Female foreign correspondents during World War II, barred from the front lines, pioneered a new genre of coverage by looking at the impact of war on everyday life. During Charlie Chaplin’s 1927 divorce from his second teenage wife, only female reporters pressed the actor on his penchant for underage girls.

But even as exceptional women defied odds to succeed, their accomplishments did little to erode stereotypes and social norms that relegated most of them to the sidelines or the women’s pages.

Even the eminent Fuller — the first editor of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s transcendentalist journal, the Dial, and literary editor of the New York Tribune — signed her columns with an asterisk, or simply “F.” Women were expected to keep their names out of print. When their articles were published, they often carried demeaning headlines like one on Mary Clemmer’s account of a Civil War battle: “The Battle of Harpers Ferry as a Woman Saw It.” When a London paper had a female war correspondent in Africa in 1881, the Saturday Evening Post quipped, “We shall now learn what the women there wear.”

Anne O’Hare McCormick — the first woman on the New York Times editorial board and to receive a Pulitzer, in 1937 — had to freelance for the Times for 14 years before she was hired full time.

Many women, including foreign correspondents Flora Lewis, Martha Gellhorn and Marguerite Higgins, managed to advance — but only one by one. “In the 1950s, women journalists inched across a swinging rope bridge toward fuller acceptance but still in single file,” Kroeger writes.

That changed in the 1970s when, buoyed by the rise of the women’s movement and passage of federal civil rights laws, female journalists took a confrontational, collective approach. A landmark 1970 complaint was filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission against Newsweek, where women were relegated to research jobs while better paid, more prestigious positions were held by men. Legal action followed at other publications, opening job opportunities and establishing protections for women who followed.

Enter my cohort of baby boom women, a transitional generation: We joined the workforce as women were making gains, but we were still outnumbered, often paid less and still facing society’s expectation that women are the primary childcare givers. (When my sons were still small, I was asked in a job interview about my childcare arrangements. Imagine a man being asked that!)

In more recent years, the battlefield expanded into family leave and flexible work schedules. Sexual harassment remained rampant, as the #MeToo movement brought to the fore. Women were rising in leadership ranks, but at a time when the industry was struggling. Ironically, Kroeger notes, women’s “greatest opportunities in the news business came as advertising revenues evaporated and readers and viewers abandoned these traditional media as their major information source.”

A 2014 study by the Pew Research Center found that between 1998 and 2012, there was little change in women’s share of journalism jobs, neither in total nor in leadership roles.

Having more women in the profession’s leadership will be key to further progress, as Siddiqui’s experience preparing for the Ukraine trip underscored. One reason her needs as a nursing woman were accommodated was because two people involved in the planning were working mothers.

“I couldn’t help but wonder,” Siddiqui said in an NPR interview, “if it had been a conversation between a couple of men, would they have maybe just automatically ruled me out and thought, ‘Well, she’s not going to be able to do this.’”

Hook has been a Washington correspondent for more than forty years, most recently for the Los Angeles Times.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.