England’s rivers pay the price for hollowed-out Environment Agency

For members of the Railway Angling club who fish the Trent where it flows past East Midlands airport on the outskirts of Derby, it has been a decade-long losing battle to stop the growing cargo hub from polluting their river.

The airport has a legal permit from the Environment Agency, the UK’s pollution watchdog, to discharge waste water containing de-icing agents between November and April each year. But if the effluent is not sufficiently diluted, it can suck oxygen out of the river water causing suffocating plumes of so-called “sewage fungus”.

According to the permit, which was updated in 2018, the discharges should not create a “significant adverse visual effect” on the river. But each year since then the fungus has returned, members of the angling club report, temporarily smothering a 170 metre stretch of the riverbank where fish such as bullheads and stone loach come to feed and spawn.

The pollution incidents are well known to the Environment Agency. The regulator issued a written warning to the airport in 2019, reviewed a fungus plume in 2020 and is currently investigating another alleged breach in 2021; but for the angling club the warnings amount to nothing more than bureaucratic slaps on the wrist.

“The problem is that every breach of the permit is just met with a warning letter,” said Gary Cyster, a retired Environment Agency fisheries inspector who fishes with the Railway Angling club and has been closely monitoring the airport’s activities since 2010.

Environmental and fishing groups say the travails of the Derby anglers are indicative of a deep malaise in the UK’s river monitoring system caused by a decade of underfunding at the agency and a system of “self-monitoring” that is not working.

Charles Watson, founder of charity and campaigning group River Action UK, said the slashing of the Environment Agency budget by two-thirds since 2010 had effectively “defunded” environmental protection in the UK.

“If you want to pollute a river you can pretty much do so in the knowledge that no one’s going to catch you; if you do get reported no one’s going to follow up, and if they do you’re not going to get prosecuted,” he said.

A scathing report published in January by parliament’s environmental audit committee found that only 14 per cent of rivers in England were rated as having “good” ecological status and not a single waterbody met “good” status for chemical pollution.

Wildlife and Countryside Link, an umbrella organisation for environmental groups including the Angling Trust and the RSPB bird charity, told the committee that English river quality was “the worst in Europe” and the progress in tackling the pollution was “extremely poor”.

Sir James Bevan, chief executive of the Environment Agency, conceded that water quality in English rivers was “flatlining” after decades of postwar improvements.

Although the slide in water quality has been going on for a decade or more, the issue has forced its way on to the political agenda after a series of high-profile sewage pollution cases and pressure from river user groups such as anglers and wild swimmers.

The 2021 Environment Act gave ministers powers to set tough new targets to reduce sewage pollution and halt the decline in species across the UK, but pressure groups say targets will be missed unless Environment Agency funding is restored and a tougher approach is taken to sanctioning polluters.

Grant funding for the agency’s environmental work has been reduced by about two-thirds from £120mn in 2010 to £40mn in 2020. Bevan told MPs this had reduced its “capacity to monitor, to enforce the rules”, adding that reversing the cut would make a “massive difference”.

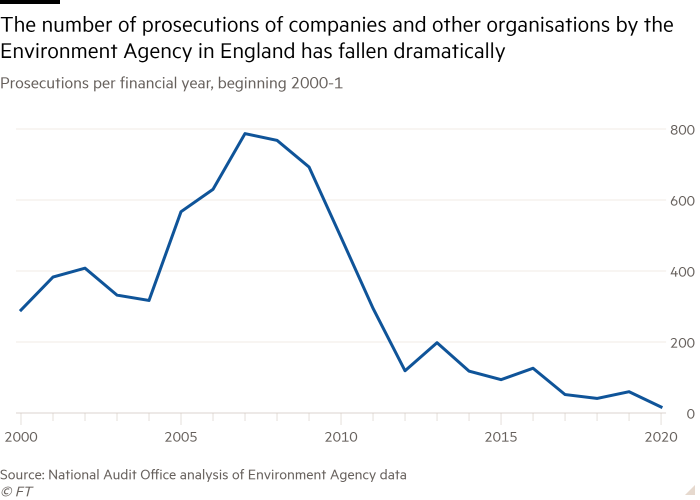

Equally important, say pressure groups, is reforming the operator self-monitoring system that was introduced in 2009, which has seen prosecutions of polluters fall by 97 per cent during the past decade.

Instead, breaches of permits are typically resolved by an agreement between the Environment Agency and the polluter to remedy any damage and address any deficiencies in the system that led to the breach in the first place.

However, groups such as the Derby Railway Angling club say their experience suggests that in practice the system of self-monitoring allows polluters to continually fail to meet their legal obligations with virtual impunity.

The spot where East Midlands airport discharges into the Trent at Castle Donington contains at least seven fish species protected under the European Habitats Directive and UK Biodiversity Action Plan, including critically endangered eels.

The club discovered in October this year that the airport had failed to collect key data about its discharges for the months of January and February — noted as another potential permit breach by the Environment Agency.

In a letter to the club, the agency said that “the appropriate enforcement action” would be taken, but Cyster was sceptical.

The airport’s failure to collect the data followed another permit breach in March 2020 after a contractor excavated gravel from the river bank during the “closed” fishing season, despite explicitly being told it was forbidden.

In a letter to the angling club in September 2021, the airport conceded the incident was “unfortunate and embarrassing” but maintained it was committed to being a “good neighbour” and would step up efforts to monitor the risk of sewage fungus plumes in the Trent.

“We will ensure that this winter [2022] we focus on the quality and consistency of the data that we record and present in compliance to the Environmental Permit,” the airport wrote. When it failed to do so three months later, it blamed a computer glitch.

“You forgive them a day, or maybe a few days of missing data, but not an entire month of data. What on earth was the Environment Agency doing? They should have been on it,” said Cyster.

East Midlands airport said it was co-operating with the Environment Agency investigations following a “number of incidents involving unplanned discharges of surface water from the airport site”, adding that it took its environmental responsibilities “seriously”.

“In parallel, the airport is implementing a surface water improvement plan that includes short, medium and long term actions to prevent further unplanned discharges,” the airport said.

The Environment Agency confirmed it was investigating the discharge of waste from East Midlands airport into the Trent. “While we cannot legally comment further at this stage, we take all reports of pollution seriously. If permit breaches are found we will take the appropriate enforcement action,” it said.

Cyster acknowledged that the agency must balance the interests of the anglers — and the environment — against those of the rapidly expanding East Midlands airport, which was designated a freeport in 2021 and includes the parcel operator DHL and Royal Mail among its major clients. Cargo volumes have grown by almost a quarter since 2019.

He noted that under the 2015 Deregulation Act, regulators have a duty to consider economic growth and said it was “quite clear” to him that the annual pollution of the river is tolerated to deliver growth.

According to minutes of meetings with the agency, the airport has said that treating the waste before it was discharged was “not a viable business option”, but Cyster argued that data showed other airports, such as Manchester and London Heathrow, pollute less.

The pollution of the Trent comes at a cost, he said. “Ten years ago, I used to catch big pike in there. I haven’t caught one for the last four.”

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.