Dick Barnett wouldn’t let basketball’s most overlooked three-peat be lost to history

If the name Dick Barnett tickles your memory a bit, you are probably a Lakers fan, and not a young one. Or, more likely, you are a Knicks fan.

If the achievements of the 1957, ’58 and ’59 basketball teams from Tennessee A&I trigger any recognition, consider yourself one in a million, a sports geek.

But there is as story there, and no matter what your age or sports interests, it is worth knowing. It’s about much more than basketball success, and it is being told in a documentary film entitled “The Dream Whisperer.” The first look at that will be presented Saturday at 7 p.m. at the Pan African Film & Arts Festival, in a theatre complex at the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza.

Barnett is the “Dream Whisperer.” He is also the former Lakers guard who played with Jerry West and Elgin Baylor from 1962 to 1965. To stir your memory, think of a skinny, left-handed jump-shooter, who kicked his legs backward as he unleashed. Think of a long, emaciated face a man who carried the nickname “Skull” because, well, he looked like one. You can also think of the player, an ace sixth man most of the time, who got traded from the Lakers to the New York Knicks, infuriating West and ending up helping the Knicks win their only two NBA titles (1970 and 1973). The Knicks beat the Lakers both times.

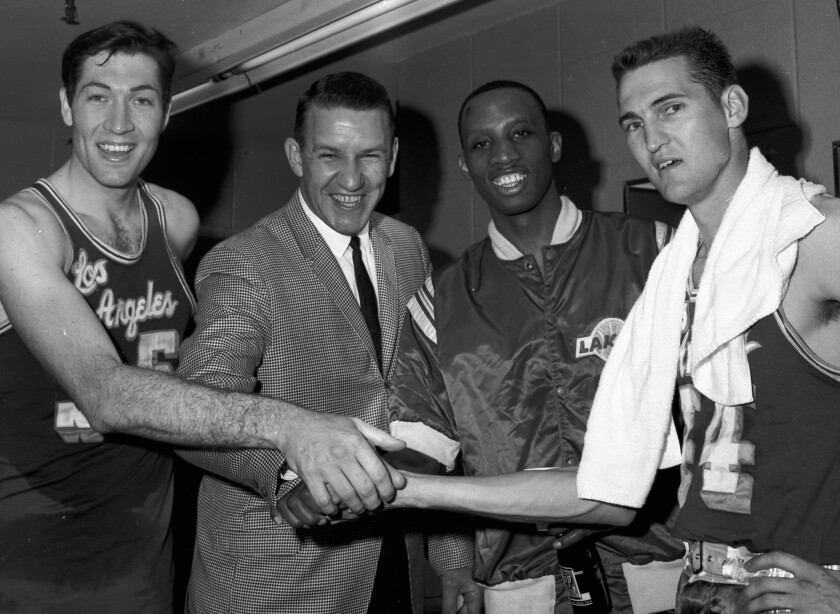

Rudy LaRusso, left, coach Fred Schaus, Dick Barnett and Jerry West celebrate after the Lakers won the Western Division to advance to the 1965 NBA Finals.

(Associated Press)

Barnett’s No. 12 jersey now hangs in the rafters of Madison Square Garden.

The heart of this story is not the Lakers, or the Knicks, or West, nor even the many celebrity voices the film presents, such as Phil Jackson, Walt Frazier, David Stern, Julius Erving, Bill Bradley, Al Sharpton and the late Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. It is Barnett’s story of, as the former Knicks star and U.S. senator Bradley calls it, “incredible tenaciousness.”

Before he was a pro, before he was drafted fourth overall by the Syracuse Nationals in 1959, Barnett played for the Tennessee A&I Tigers, a school in Nashville that is now Tennessee State. His team won the championship of the NAIA (National Assn. of Intercollegiate Athletics) three times in a row, and that was just five years after all-Black schools were even allowed to compete in any national basketball tournament that meant their presence would integrate the competition. The Texas Western Miners, with five Black starters, stunned the college basketball world in 1966 by beating Pat Riley’s Kentucky in the NCAA final. The A&I Tigers had won a national title a decade before and done it three times.

But it turned out that that three-peat had little traction in the sports world. The NAIA division featured a bunch of smaller schools and the sports world related more to Disneyland than Branson, Mo.

By the mid-1970s, Barnett was done with his NBA career. He had torn an Achilles tendon and doctors told him he might never play again. “I started to think about what I was going to do with the rest of my life,” he says.

It was a burning question because education takes you places in life, and Barnett had almost none. Growing up in the opulence of Gary, Ind., he was a bad student at Roosevelt High, but a good enough basketball player to lead his team to the Indiana State finals, where it lost to Crispus Attucks High and somebody named Oscar Robertson. Barnett was from the ghetto and expected to stay there.

“The only white people I ever saw in Gary were police,” he says.

One day, a man named John McClendon, who would become a Hall of Fame coach, offered him a scholarship to play for him at Tennessee A&I.

“I never heard of the place,” Barnett says.

With no better options, he went, became captain of the team and was the star player of A&I’s three-year NAIA sweep.

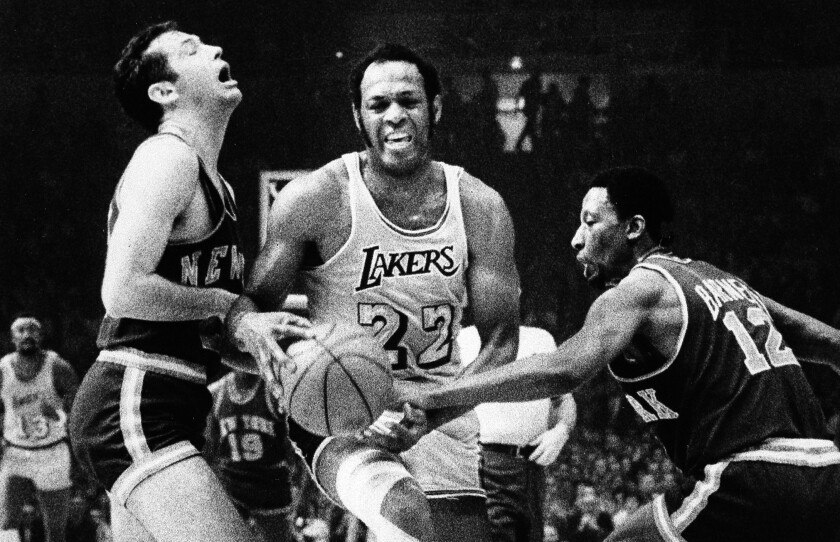

Lakers’ Elgin Baylor maneuvers his way between New York Knicks’ Bill Bradley, left, and Dick Barnett on May 1, 1970, at the Forum.

(Associated Press)

When basketball ended, he knew school was the next step, the only step. While with the Lakers, he made the trip from the west side of Los Angeles to take classes at Cal Poly Pomona and eventually went back to finish his college degree there in physical education. He followed that with a master’s degree from NYU in public administration and a doctorate from Fordham in education. So, it was Dr. Richard Barnett, professor and author of more than 20 books, who paused one day with a realization that there was something else he needed to take care of — getting his NAIA three-peat team into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

It shouldn’t be difficult, he reasoned. His team had accomplished this unbelievable milestone in the midst of the Jim Crow era of southern state laws that legalized racial segregation. He and his teammates had to stay in private homes when they traveled to games. After they won their first NAIA title, Barnett rushed back to downtown Nashville to participate in a restaurant counter sit-in, where no Blacks were allowed. The Naismith Hall of Fame people would listen to all this and, in a new world of racial understanding, quickly decide to honor this team.

His first try was 2011. He was turned down then and every year for the next seven. It became more than a campaign for Barnett; closer to an obsession. “It was a story that must be told,” Barnett says. “People were dying. This was a team that would be lost to history.”

In 2011, George Willis of the New York Post wrote a column about Barnett’s efforts.

“I had never heard about this,” Willis says. “I thought Tennessee State was a football school.”

The class of 2019 Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame inductees, or their representatives, pose for a photo in Springfield, Mass. From left to right: Chuck Cooper III, accepting on behalf of his late father Chuck Cooper; Susan Braun, accepting on behalf of her later father Carl Braun; Al Attles; Vlade Divac; Ron Coville accepting on behalf of his father-in-law, Bill Fitch; Bobby Jones; Sidney Moncrief; Jack Sikma; Dick Barnett for Tennessee A&I; Linda Price for Wayland Baptist; Teresa Weatherspoon; and Paul Westphal.

(Jessica Hill / Associated Press)

In 2016, Willis wrote again. “My theme was, ‘What is taking so long?’”

A former owner of the Atlanta Hawks, George Peskowitz, read the first Willis column. He called a filmmaker friend, Eric Drath. For eight years, cameras followed Barnett, now 85 and walking with a cane.

“When he finally got the team in the hall in 2019,” says Willis, one of the documentary producers, “there was plenty of film.”

At the 2019 ceremony in Springfield, Mass., his friend West stood next to Barnett on the podium, shook his hand and presented him for his acceptance speech. Barnett had reached the top of his mountain climb, and the NBA logo was there to celebrate with him.

West said this week that he will be at the Saturday showing of “The Dream Whisperer,” adding that it will be nice to watch something accurate and positive. That would be a reference to his current battle with HBO over its portrayal of him in the current series “Winning Time.” West, through his lawyers, has demanded a retraction and apology from HBO.

“The series made us all [the Lakers] look like cartoon characters,” West says. “They belittled something good. If I have to, I will take this all the way to the Supreme Court.”

Even that probably wouldn’t take as long as his friend Barnett’s journey to Hall of Fame recognition for a team of basketball legends that few knew. At least until now.

For all the latest Sports News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.