David Crosby liked to take credit for just about everything that happened in the 1960s.

Last year, he told Mojo magazine that he introduced George Harrison to Ravi Shankar, who introduced Harrison to the sitar, which in effect put Crosby’s fingerprints on the Beatles’ 1966 album, “Revolver.”

In classic Crosby form, it was a self-mythologizing boast — and basically true.

A cultural lion both beloved and criticized in roughly equal measure, Crosby defined the contradictions of his era. He was a voice of his generation’s most cherished ideals and its most pungent caricature, the man who wrote the willowy folk classic “Guinnevere” and a sybaritic braggart whose excesses required two memoirs to fully digest.

With his death on Wednesday at age 81, Crosby leaves a larger-than-life hole in the culture. As Lynn Goldsmith, the rock photographer, put it on Instagram: “Even if David was an abstract presence in your life, it’s like having a lighthouse in the distance suddenly go dark. We have one less landmark to navigate by.”

From the time he broke through with the Byrds in 1965, adding sophisticated folk harmonies to chiming rock ‘n’ roll, Crosby surfed the frothy edge of the countercultural wave like few others, defining the sunburst hippiedom of 1960s California. He played Jane Fonda’s birthday party in 1965, took LSD with the Beatles, performed at Woodstock, made the cover of Rolling Stone and allied himself with the Hells Angels, his fringe-jacketed hippie-rebel image inspiring Dennis Hopper’s character in “Easy Rider.”

The son of a successful Hollywood cinematographer, he was famously kicked out of the Byrds for espousing a JFK assassination conspiracy at the Monterey Pop Festival, establishing a trend that was destined to last for decades. His indulgences, prickly opinions and unfiltered ego always threatened to eclipse his talent — which, ironically, centered on his uncanny ability to disappear inside angelic harmonies with Graham Nash, Stephen Stills and Neil Young. As recently as last year, he was still stoking public feuds with the men with whom he sang “Teach Your Children” in 1969. As he told me a few years ago, the 1971 CSNY album “4 Way Street” “was the most accurate album title in history.”

Despite a history of self-sabotage, Crosby wanted foremost to be judged by his music. Paul Simon, he said, had a “Napoleon complex” and “old weird Bob [Dylan]” is “crazy as a f— fruit fly,” but “you look at an artist and you have to look at their art. Their art speaks for them better than they do. That’s where you see who they are. Not their bad-boy behavior. Not me trying to get laid until I wore my d— off. You know, ‘How many girls can I get in this bed?’ Not any of that stuff. That’s not important.”

In the next breath, of course, Crosby was happy to give chapter and verse on his fabled sex life, invariably referencing his famous ode to a threesome, “Triad.” He just couldn’t help himself.

Neil Young, left, David Crosby and Graham Nash perform at the Santa Cruz Civic Auditorium in 1977.

(Ed Perlstein / Redferns)

It was his art, of course, that built the edifice for his soap box. Bob Dylan called him an “architect of harmony” (as well as a “colorful and unpredictable character”). Crosby’s vocal arrangements, on the Byrds’ “Eight Miles High,” which he co-wrote, or CSNY’s “Helplessly Hoping” and “Find the Cost of Freedom,” rivaled those from Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys in grandeur and beauty.

When Crosby finally crashed on the shoals of 1970, getting addicted to heroin after the death of his girlfriend in a tragic car accident, he also made what is now regarded as his finest album, “If I Could Only Remember My Name.” The record was trashed by major critics like Lester Bangs and Robert Christgau, the latter calling it a “disgraceful performance.” But the album, featuring Joni Mitchell and members of the Grateful Dead, proved lasting, exalted by subsequent generations of critics as a touchstone of experimental folk and psychedelia. On songs like “Laughing” and “Cowboy Movie,” Crosby pulled off a fragile alchemy of complex vocal arrangements atop shambolic jamming that melded in an eerily private reverie. It’s one of the best albums of its time.

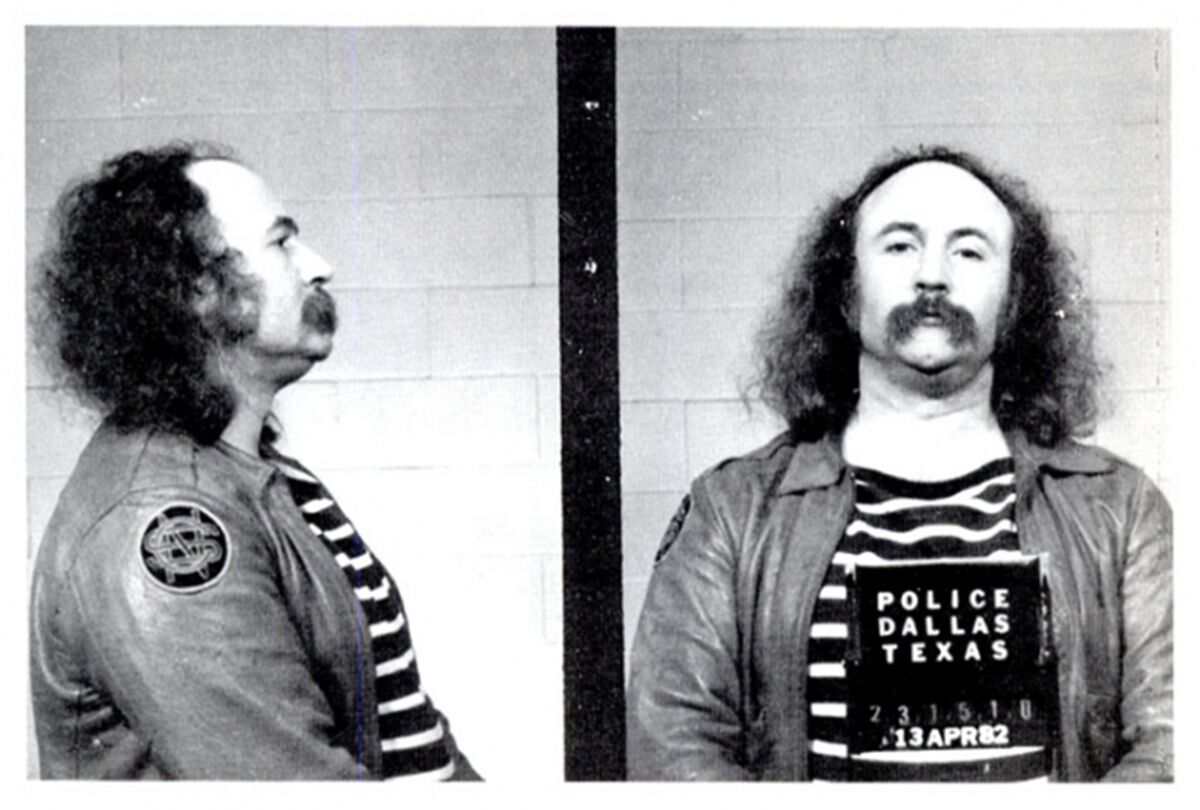

It also marked the beginning of a decade and a half of public and private degeneracy that eventually found Crosby strung out on crack cocaine, financially ruined and in prison by 1986.

David Crosby, after being charged with drug and gun possession in April 1982.

(Donaldson Collection / Getty Images)

I first met Crosby in 1990 when I recognized him on a street in Freeport, Maine (he was shopping at L.L. Bean with his wife, Jan Dance). I’d seen him a few months before on his obligatory anti-drug college tour following his stint in a Texas penitentiary. He was funny and obliging, showing off his Harley Davidson (which he later crashed) and assuring me that, despite his public anti-drug stance, psychedelics were well worth taking and that he and Jan took LSD once a year on a beach vacation.

The ‘60s dream was alive and well.

Through the years, Crosby took on a lovable, walrus-like mien, adding a dose of eyewitness credibility (and eyerolling self-regard) to numerous rock documentaries. Few could match his impish enthusiasm: His tale of meeting John Coltrane in a bathroom in the mid-‘60s, in the surprisingly candid documentary “David Crosby: Remember My Name,” is nearly as visceral an impression of what it was like to experience John Coltrane as listening to John Coltrane.

The next time I saw Crosby was on his ranch in Santa Ynez in 2014, to interview him for my biography of Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner. Even 50 years on, he smarted from the critical lashing his solo album had taken: “My first solo record, which is selling now to this day, and is a legendary f— record — they said it was ‘a mediocre piece of work.’”

When I emailed him the next week to say I considered the album his greatest achievement, Crosby shot back: “I have stuff in the can right now as good or even better. But thanks.”

His 2014 album, “Croz,” sparked a late-life renaissance that led to a series of surprisingly inspired albums, his voice still supple and feathery after years of abuse. Crosby’s fresh output (five new albums in eight years, including last year’s “For Free”) fell squarely under critic Edward Said’s concept of “late style,” the period when an aging artist (quoting philosopher Theodor Adorno) “abandons communication with the established social order of which he is a part and achieves a contradictory, alienated relationship with it.”

Certainly Phoebe Bridgers would agree.

Few were as readymade for Twitter as David Crosby, who got on the platform in 2011 and began firing off tart opinions on Kanye West (“my dog could beat him at chess”), the Doors (“crap”) and Joni Mitchell (“the greatest living songwriter”). He also rated images of hand-rolled joints for style and functionality. When Bridgers, a young indie songwriter, smashed her guitar on stage during a performance on “Saturday Night Live,” Crosby tweeted that it was “pathetic” and “stupid,” a distraction from her songwriting, which he deemed second rate. A flame war ensued. Bridgers called Crosby a “little bitch,” and the public sided with Bridgers.

But if Crosby acted like a guy whose place in history made him too big to cancel, maybe he had a point. His music, despite the man, remains unavoidable. Case in point: Phoebe Bridgers’ latest effort is a supergroup called Boygenius with two other singer-songwriters, Julien Baker and Lucy Dacus, and featuring layered and interweaving harmonies set to indie rock.

Wittingly or not, it’s an echo of and an homage to the influence and legacy of David Crosby.

Joe Hagan is a special correspondent for Vanity Fair.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.