Been about that bandana print

At my charter high school, we had a strict uniform: logo-branded polos, black slacks, black belts and black shoes. The look was built on seriousness. We all knew why, even without saying it. We were allowed Black hair accessories, though, so one day, I decided to wear my paisley bandana. It wasn’t technically against the rules, but I knew better. I hid it in my backpack and put it on once I got to school.

In a home where even solid red and solid blue were forbidden for fear of gang association or affiliation, I wouldn’t dare leave the house wearing a bandana, but I thought I was safe at my Financial District downtown L.A. school. I could wear my cute little bandana and take it off before I went home. During third period, one of the wardens pulled me out of class, and I was greeted by my stern vice principal at the time, Mr. Mac. Not the one you want to mess with. The bandana was so old and so worn by grandma when she used it as a wrap for my constantly sprained wrists, you could hardly see the white teardrop emblems. But I caved and took it off.

Still, it was an irresistible garment: so easily folded, tied and tucked to look like the headbands I got from Claire’s or the beauty supply store. I yearned to wear it. I couldn’t stop thinking about the print, the beauty of the paisley, the feeling of wearing it. A black bandana, to me, was a neutral way of showing connection to my neighborhood and to those who donned it before me — Nipsey Hussle, Tupac and, like, Dipset.

What’s made paisley transcend time and cultures can be found in the simple beauty of a teardrop. Each layer of a single drop reveals another world and then another. Here, Salem Mitchell wears Amiri dress and personal jewelry.

(Zamar Velez / For The Times)

Paisley, in case you haven’t noticed, is everywhere — Jacquemus, YSL, Loewe. But it’s always been a distinct symbol in Los Angeles. Its sprawling design parallels this city’s depth and grandeur.

Many of us can recall our earliest memories with the print: from the fine silks and rugs (on which the patterns originated, in India and Persia) to grandma’s woven paisley purse to stiff 99-cent store bandanas. What’s made paisley transcend time and cultures can be found in the simple beauty of a teardrop. Each layer of a single drop reveals another world and then another. In a dramatic curl, the drops often have a leaf or flower-like border, sometimes a solid border, giving structure to its shape, or a thicker border with dots — maybe sun rays — and, at the heart, an open-face flower.

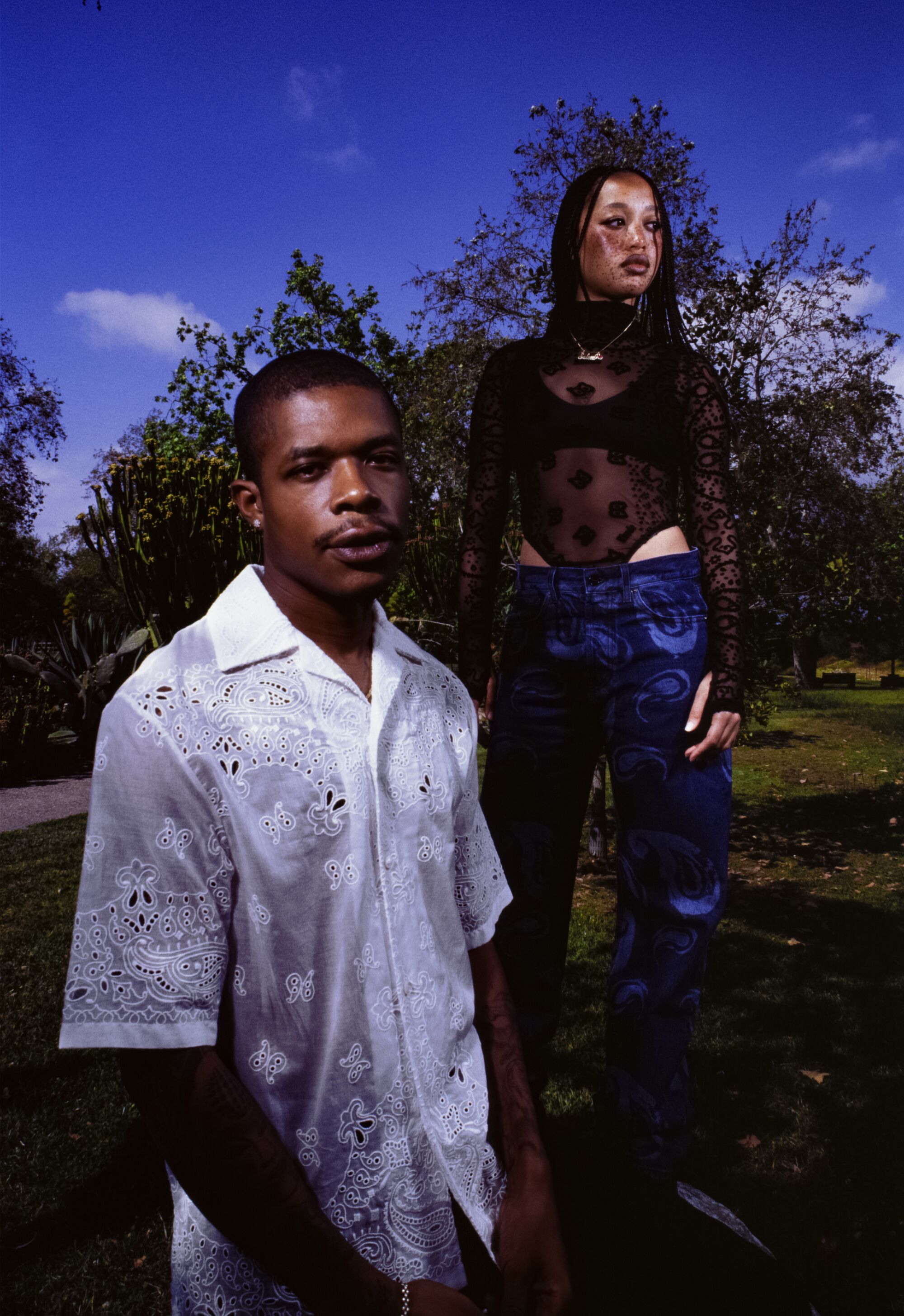

Like this city, there’s a protean quality to the bandana print pattern. It might look different where you’re at. Here, Barrington Darius wears Rhude top, Amiri bottoms and shoes, and personal jewelry.

(Zamar Velez / For The Times)

Salem wears Amiri dress, Lujo Depot bottoms, and New Rock shoes. Barrington wears a Rhude top, Amiri bottoms and shoes, and personal jewelry.

(Zamar Velez / For The Times)

Like this city, there’s a protean quality to the pattern. It might look different where you’re at. You might see it quietly embellished on the border of a $100,000 antique, hand-knotted rug or on a cashmere shawl, the drops long and slim, pulling away from the center to leave open space. On bandanas, paisley “teardrops” are more understated. They’re dotted like little raindrops or flower petals caught and encased in ornate frames. Where the drops are sparse in detail, the frame delivers in an undeniable elegance and gaiety. In contrast to its rigid square border, a softness is found from the stems that flow in and out of each other, blossoming flowers and teardrops like loose petals. When draped from a denim pocket, the drops look like they trickle down into a river and pour from a waterfall.

It’s just pretty.

Even though the pattern has started to pop up all over L.A. again, you can’t just go wearing a bandana however, whenever, wherever now. If you’re going to do it, you have to do so with finesse. There’s a discourse, a conversation happening. Paisley is the kind of print you must mold yourself to, meet it on its terms, not yours.

Even though the pattern has started to pop up all over L.A. again, you can’t just go wearing a bandana however, whenever, wherever now. If you’re going to do it, you have to do so with finesse. Here, Barrington wears Amiri top, Kapitol bottoms, and Toga shoes. Salem wears a Rhude top, Jacquemus jeans, and New Rock shoes.

(Zamar Velez / For The Times)

Paisley is the kind of print you must mold yourself to, meet it on its terms, not yours. Here, Salem wears Rhude top, Jacquemus jeans, and New Rock shoes.

(Zamar Velez / For The Times)

Having a “right and wrong way” to wear a bandana is hardly a new concept. Spanto, founder of Born X Raised, having been part of the life himself, has a deep reverence and profound respect for the paisley print. It’s why he’s used it only twice in the history of the brand, most recently on a fluffy white fleece jacket with a navy symmetrical blue paisley print.

Getting dressed was “the best part” of the life, Spanto said. It was like a ritual for him: pulling the ironing board out from the wall at 6 each morning, ironing his fit, including his white paisley bandana. Pressing it and folding it so that it was crisp when it hung from his pocket in a perfect rectangle.

You can tell that contemporary designers are transferring this same care when repurposing the print in their clothing, drawing from their own memories. Kacey Lynch, founder of Bricks & Wood, remembers seeing bandanas at the Slauson swap meet, tucked into people’s pockets or wrapped around their necks and arms. In terms of her brand’s designs, she says, “[W]e mix it up just enough so that it feels new, but it also [feels like] something that you’ve seen before, [that’s] familiar to your story, which is kind of the name of the game in streetwear.”

Memories of a divided city remain present in the print. But there is unity baked into the bandana as well. Star Angel, designer for Sincerely GhettoBird, grew up on a street where colors — be it bandanas or skin complexion — were a source of tension. But she also recalls her stepfather, an ironworker, and his colleagues taking off their construction helmets after a day of work to reveal the yellow, red, orange and blue bandanas they wore to catch their sweat.

Memories of a divided city remain present in the print. But there is unity baked into the bandana as well. Barrington wears Jdosax top by Jesus Mendoza, Justin Mensinger bottoms, and Toga shoes.

(Zamar Velez / For The Times)

A good print is distinct but part of a lineage. Here, Salem wears Miaou top, Lujo Depot bottoms, and personal jewelry.

(Zamar Velez / For The Times)

“People always respond to the black and brown bandanas together,” Angel said of the hoop earrings she created stitching the colors together. “This reminds me of Black and brown unity. That’s how it should be.”

Paisley is a pattern with a past. The lines begin somewhere, but the question of where they end is a function of where the eyes choose to meander. Bandana print is visually inseparable from its history. The memory of what it was lives with us now — and will continue into the future. Paisley is a connective thread — there are layers to unfurl, places to go. Peeling back one dotted, coiled or solid layer after the other unlocks a feeling. The curls dance across hoodies, scarves and candles with vines that start nowhere and continue everywhere.

A good print is distinct but part of a lineage. The not-so-distant cousin of bandana print is Kente or Otomi — two cloths that communicate a record of cultural history, a collective heritage, through details. Bandana print says something. Always. In my case, my black bandana shouted through the halls of my school: “This is where I’m from.” I still cherish that. I still wear South Central, no matter what I have on. And when I see bandana print in the wild, I feel connected to it in a way that’s palpable. The legacies of those who brought the pattern to life are still present. Something of how they did it, who they were when they wore it, remains. Bandana print represents an energy — and a culture — that is very much alive.

Paisley is a print that represents an energy — and a culture — that is very much alive.

(Zamar Velez / For The Times)

Models: Barrington Darius, Salem Mitchell

Hair: Anthony Martinez

Makeup: Matthew Fishman

Styling assistant: Carmen Madera

For all the latest Life Style News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.