Australian central bank tightens monetary policy to deal with price surge

The Reserve Bank of Australia has dumped its policy of yield curve control, becoming one of the first large central banks to act against a post-pandemic surge in prices.

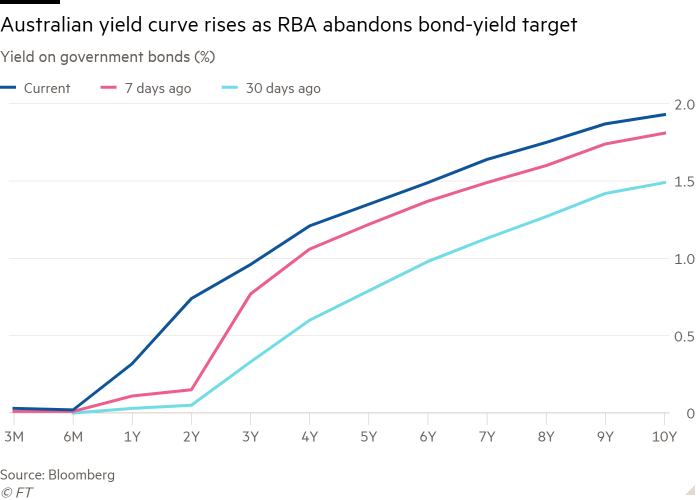

The central bank said on Tuesday it would no longer try to keep the yield on three-year bonds at 0.1 per cent, following a week of turmoil in short-term bond markets during which yields soared after the RBA declined to defend its cap.

The shift makes the RBA one of the first central banks from an advanced economy to tighten monetary policy in the wake of the pandemic and will heighten pressure on the Bank of England to consider an interest rate rise when it meets on Thursday.

“The decision to discontinue the yield target reflects the improvement in the economy and the earlier than expected progress towards the inflation target,” said Philip Lowe, governor of the RBA, after a meeting of the central bank’s board.

But while the RBA relaxed its control on the yield curve, it also signalled it was in no hurry to raise short-term interest rates, promising to keep them on hold until inflation was sustainably within its target range of 2-3 per cent.

“This will require the labour market to be tight enough to generate wage growth that is materially higher than it is currently,” said Lowe. He added that achieving that would probably take some time and that the central bank was prepared to be “patient”.

The RBA kept overnight interest rates at 0.1 per cent and maintained its pledge to buy government bonds at a rate of A$4bn ($3bn) until at least mid-February 2022.

The delicate balance of relaxing yield curve control while pledging to keep interest rates low for some time illustrates the dilemma for central banks in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis.

Economies reopening after the pandemic have been confronted by significant disruption to global supply chains, putting upward pressure on prices and leading markets to expect an earlier rise in interest rates.

Australian consumer price inflation is running at a year-on-year rate of 3 per cent, according to figures released last week, driven by fuel and housing costs.

Although higher short-term inflation is unsettling, central bankers are reluctant to raise interest rates because economies have not fully recovered from the pandemic. They fear the return of deflationary pressures that defined the 2010s and led to zero interest rates across many advanced economies.

The RBA adopted yield curve control — a policy first used by the Bank of Japan — in March 2020. It set overnight rates and three-year yields at 0.25 per cent, then cut them to 0.1 per cent in November 2020.

Under yield curve control, a central bank promises to buy as many bonds as needed to keep yields below a certain level. That allows it to control longer-term interest rates and add extra monetary stimulus when overnight rates are already at zero.

Last week, the RBA let the three-year yield rise through the cap. It traded at 0.975 per cent after the monetary policy decision, suggesting overnight interest rates would rise several times before 2024.

The shift makes the RBA the first central bank to retreat from a yield curve control policy, setting an important precedent for the BoJ, even though the Japanese central bank is unlikely to drop its policy for several years.

Additional reporting by Hudson Lockett in Hong Kong

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.