Appreciation: Architect Arata Isozaki’s design for MOCA launched his global career. It almost didn’t happen

In March 1982, the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles staged a press conference to unveil new designs for its Grand Avenue building by Japanese architect Arata Isozaki. The event marked an important milestone for a project that had been years in the making. But as the presentation progressed, things went off the rails.

For Isozaki, MOCA — his first international project — was a critical commission. At the time, he was well known in his native Japan, where he had a number of successful buildings under his belt, including the Museum of Modern Art, Gunma, completed in 1974. That structure consists of adjoined cubes that rest on unarticulated columns. In its geometries, you can see some of the influences that ultimately materialized in the building he designed for MOCA.

In the spring of 1982, however, the commission for MOCA was far from assured. At the press conference, Isozaki unveiled a boxy form that disappointed. Times design critic Sam Hall Kaplan described it as “surprisingly bland,” and critic Paul Goldberger, then writing for the New York Times, dubbed it “fundamentally dull.” As those assembled in the room began to pepper Isozaki with questions, the architect broke with press conference protocol to announce that he did not endorse the concept and had been wheedled into producing it by the museum’s building committee, led by computer mogul Max Palevsky. What’s more, he was thinking about resigning.

Controversy, of course, ensued. Pontus Hulten, then MOCA’s director, and his deputy, Richard Koshalek, also threatened to resign unless the board gave Isozaki greater creative freedom. Palevsky found himself sidelined. But he refused to go quietly: He sued the museum for the return of his donation, arguing that he had been promised architectural control. (The case was later settled, largely in the museum’s favor.)

A view of MOCA’s facade on Grand Avenue in 2019.

(Elon Schoenholz)

With Palevsky out of the way, Isozaki was free to revise his designs for MOCA. And it was from that process that emerged the museum we know today: a 98,000-square-foot compound of red Indian sandstone, capped by 11 pyramidal skylights and a barrel-vault library supported by a pair of pilotis.

It is a peculiar building. Working around a steep hill and preexisting structures, the architect had to go through all manner of contortions to make the building work. But MOCA has nonetheless served as one of Isozaki’s most important pieces of architecture.

Of the building, Washington Post critic Benjamin Forgey wrote, “There is no bombast here, no shallow self-advertisement, no straining for effects. Instead, there is modesty and a calm mastery of paradox: Though obviously new and memorably odd, the building looks as if it had been here for ages.”

In 2019, when Isozaki was awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize, the announcement lauded MOCA’s “eloquent awareness of scale.”

Isozaki, a singular architect whose eclectic buildings bear a world of influences, died at his home in Okinawa on Wednesday at the age of 91. His death was announced in a statement by his longtime companion, gallerist Misa Shin, and was confirmed by a member of his studio. The architect was in fact the subject of a solo show at Shin’s gallery that concluded four days before his death.

English architect Peter Cook, one of the founders of the influential avant-garde group Archigram, hailed Isozaki as “ONE OF THE GREATS” in a Facebook post.

Johanna Burton, MOCA’s director, stated via email that the museum has been “indelibly imprinted” by Isozaki, with his “groundbreaking ethos of contextual awareness, continual change, and even unrest creating the perfect setting for dialogues around contemporary art. Its iconic materials and spaces give the museum a clear identity, yet one with a sense of anticipation of other things to come.”

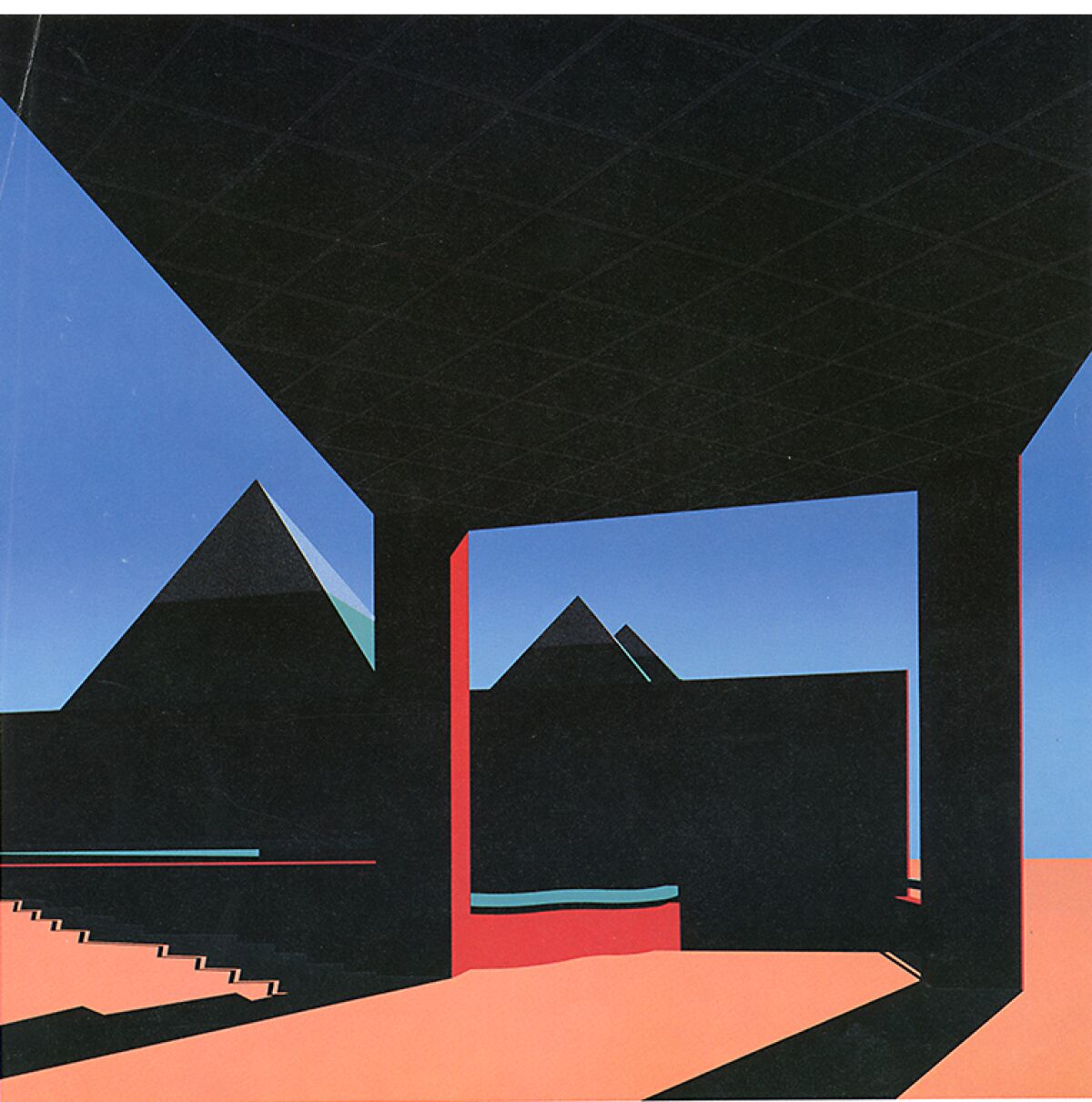

“MOCA #2 Series,” 1983 — one of Arata Isozaki’s elegant renderings of his design concept for the museum.

(Arata Isozaki)

Born in Ōita, on the southern island of Kyushu, on July 23, 1931, Isozaki was the eldest son of a successful rice shipper who also wrote haiku poetry. If his early youth was idyllic, his teen years were far less so. Ōita lies squarely between Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Isozaki’s formative years were spent reckoning with the devastating wreckage of two U.S. atom bombs.

“I have a strong image that everything I do will always be destroyed or ruined,” he told Times art critic William Wilson in 1991. “That image became my hidden trauma. … I never had the idea of becoming an architect, but in some way I thought, ‘We have to reconstruct this destroyed situation.’”

This instinct led him to pursue his studies at the University of Tokyo. While still a student, he took a job working for Kenzo Tange, the renowned Modernist who designed Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Museum, and who was then working on the iconic Yoyogi National Gymnasium for the 1964 Olympics.

Isozaki buttressed these formative experiences with travel around Japan, Europe and the U.S. What would emerge from those journeys was an idiosyncratic practice that fused a range of Western traditions with Eastern ones. In his work, for example, he was as intrigued by the barrel vault — a form common to Roman architecture — as he was by Japanese concepts of in-between space, known as ma.

In the early ’60s, Isozaki launched his own firm and began to work on a range of residential and commercial projects. In his earliest days, his designs brought a wry humor to the weighty materials of Brutalism. His Ōita Medical Hall, completed in 1960, is composed of a horizontal cylinder that rests on four concrete legs. The design resembles a robotic animal — one that Isozaki once likened to a piggy bank. The following decade, he designed a clubhouse for a golf course in the shape of a question mark. “It was a private joke,” he later said, “asking why the Japanese play so much golf.”

Arata Isozaki, left, and Misa Shin arrive at the 2019 Pritzker ceremony in Paris.

(Ludovic Marin / AFP via Getty Images)

What followed was a decades-long career in which the architect rarely repeated himself.

The ’80s-era Tsukuba Center Building in Ibaraki brought together the patterns of the Italian Renaissance with a Japanese garden. A corporate building for Walt Disney Co. in Orlando, Fla., blended the whimsical Disney color palette with a stark arrangement of contrasting geometric forms. The relentlessly futuristic Palau Sant Jordi, a sports hall designed for the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, referenced Catalan vault techniques. It was also a remarkable feat of engineering: The steel frame of its roof was assembled on the ground and then hoisted into place over 10 days — during which even the king of Spain turned out to check on the progress.

Isozaki once attributed the shifting nature of his aesthetics to the uncertainty he experienced coming of age in postwar Japan. “Change became constant,” he told a reporter in 2019. “Paradoxically, this came to be my own style.”

His uniqueness of style also applied to the way he carried himself: Isozaki eschewed ties, instead preferring the loose ensembles created by his friend, fashion designer Issey Miyake. In addition to his architecture, he was a teacher and writer, producing books that explored some of his influences at length. This included “Japan-ness in Architecture,” published in 2006, which articulates the concepts that help define Japanese architecture — among them impermanence and ritual.

When he received the Pritzker at the age of 87 — decades after other architects of his generation, such as Fumihiko Maki, were honored — Isozaki took the award in stride. “It’s like a crown on the tombstone,” he quipped to the New York Times.

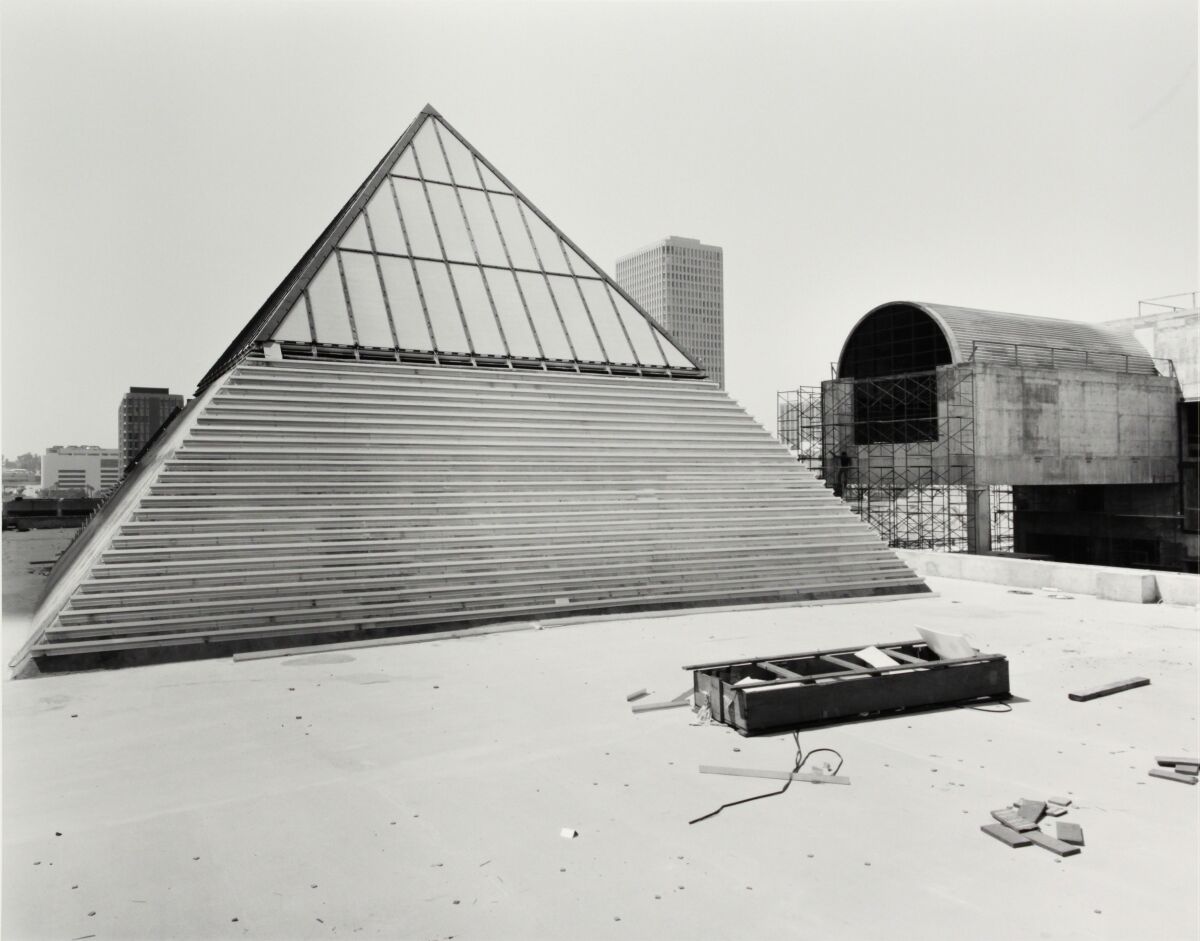

Joe Deal, “Large Pyramid, Gallery A and Library,” 1986, shows MOCA under construction.

(Joe Deal / MOCA)

Foundational to Isozaki’s success was MOCA. But even after the revolt against Palevsky, the institution didn’t make things easy for him.

On top of combative patrons seeking to strip his designs of their quirks, there were the museum’s physical and political complications. Bunker Hill’s grades are infamously steep, making any construction a challenge. For structural reasons, Isozaki was required to adhere to the column grid of the existing parking structure below. And there were the many compromises with the developer of California Plaza, the site where MOCA is located. The building could not be too tall so as not to compete with surrounding towers, nor could it block pedestrian access between Grand Avenue and the rest of the plaza. These conditions sent much of the museum below grade.

It’s the sort of tall order that would tie any architect into knots: Design a new institution for Los Angeles, just don’t make it so prominent that it interferes with commercial real estate interests.

Isozaki nonetheless created some remarkable spaces within these constraints. Many critics have been dissatisfied by the descent into the museum, but I find the transition from street-level hubbub to the quiet of the galleries a thoughtful one — Isozaki integrating his concepts of ma into a challenging site.

Over the years, MOCA‘s skylights have been covered over — eliminating one of the most notable effects of Isozaki’s design.

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times)

Unfortunately, unsympathetic changes haven’t helped make the case for the buildings. Over the years, MOCA has painted over its pyramidal skylights to prevent the sun from damaging fragile works of art. This has obscured one of the building’s best features: the daylight that used to cascade into the galleries from above. The most dramatic of these was a large skylit room on the south side that Frank Gehry once described as “worth the whole building.”

The only light there now is artificial.

When Klaus Biesenbach began his short-lived tenure as MOCA’s director in 2018, he launched a study to see what could be done to restore the skylights. Countless advances have been made in light-filtering technology since the 1980s to make illuminating the galleries with natural light a possibility. A representative for the museum says the intention is to restore the integrity of the skylights, but there is no renovation timeline in place.

It’s a move worth exploring. Isozaki may be gone, but it’s never too late for MOCA to finally finish the job of giving him the building he deserves.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.