Review

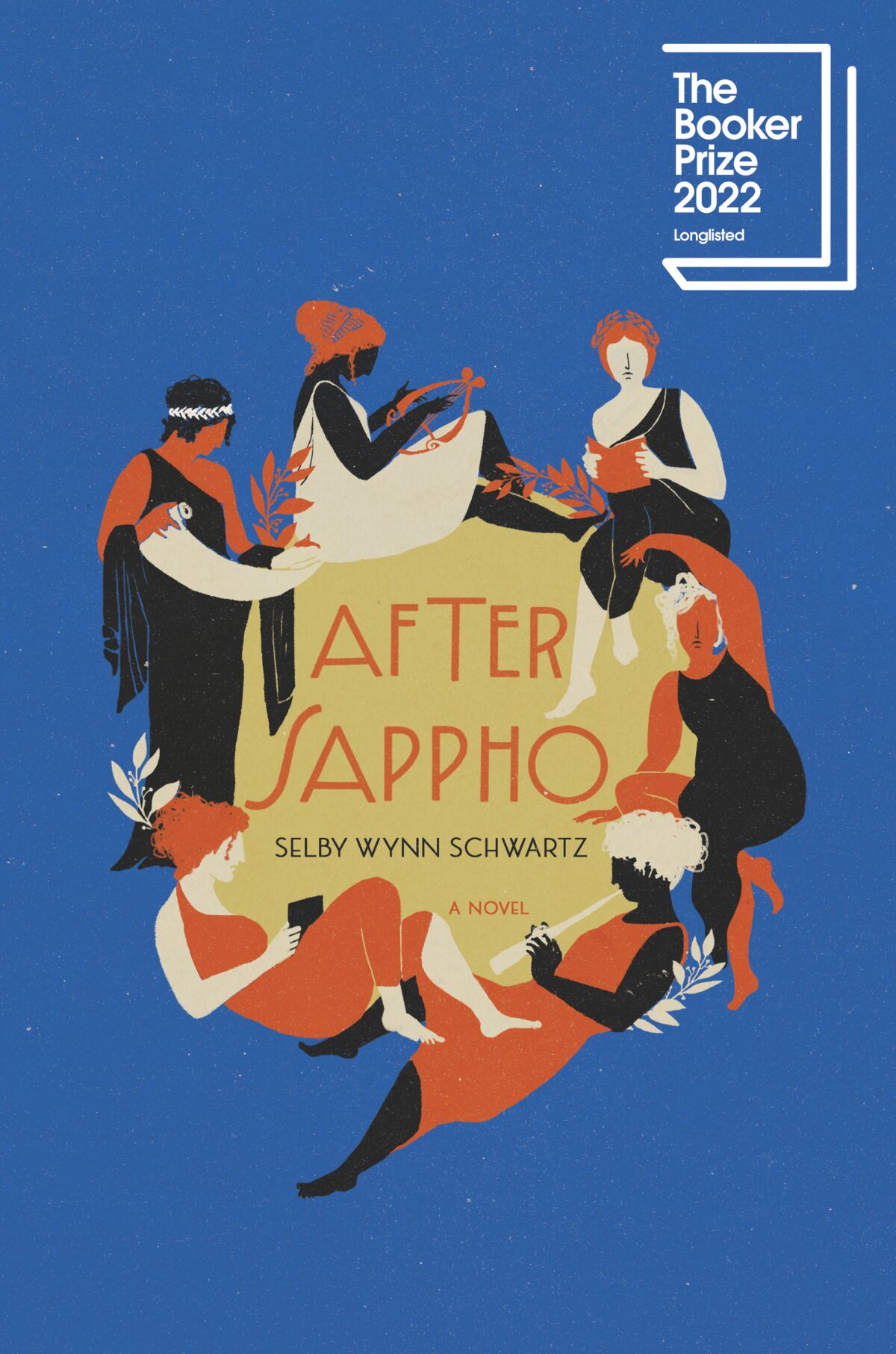

After Sappho

By Selby Wynn Schwartz

Liveright: 272 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Selby Wynn Schwartz’s “After Sappho” has it out for linear narrative in a big way. Maybe narrative has never really served women anyway — has never properly told their stories or helped them write their own. Maybe, you think while reading this debut novel, it’s payback time.

“After Sappho,” which was longlisted for the 2022 Booker Prize, feels like a Greek chorus’ group chat, with voices that slide out of their identities and into new ones, stories that sputter out for chapters and then come roaring back, big whirls of nothingness smack in the middle. If I had to write its publicity copy, I’d call it a fictional collective biography of a real-life group of Sapphists — lesbians, yes, but more particularly spiritualists devoted to the famous but elusive ancient Greek poet whose work survives only in fragments — coupled with the political history of the women’s movement in Italy. But that description has way too much solidity. The novel is diaphanous, celestial, disembodied — sometimes to its benefit, sometimes not.

A thousand milquetoast histories might have been written from Schwartz’s material, which is largely taken from the early 1880s to the late 1920s. Her loose group of characters includes writer and salon hostess Natalie Barney, painter Romaine Brooks, novelist and provocateur Radclyffe Hall, modern dance pioneer Isadora Duncan, famed actor Sarah Bernhardt, avant-garde architect Eileen Gray, anarcha-feminist Anna Kuliscioff and prima ballerina Ida Rubinstein. Hovering around them are lesser-known but equally arresting women.

“The first thing we did,” the novel begins, “was change our names. We were going to be Sappho.” Who is we? The nameless women who want to shed their strictures like snakeskins. The secretly educated women driven to needlework when what they want is to plunge a sharp point into a man’s chest. The lesbians who are run underground again and again by politicos bloviating about moral indecency. Anyone, really, who, in the collective narrator’s opinion, “wanted what half the population had got just by being born.” And what does it mean to be Sappho? For these women, to create fearlessly, live unencumbered and screw whomever they damn well please.

If women’s lib is commonly thought to have progressed in successive wavelets over the better part of a century, “After Sappho” wants to rewrite that linear story into a swirl — not waves but eddies. In the early 1880s, Leslie Stephen conceived two legacies: He began work on “The Dictionary of National Biography,” a definitive timeline of nearly 30,000 eminent dead Brits. And he fathered Virginia Woolf, who would go on to unshackle the written word from the constraints of time. Schwartz’s pseudo-history is an endorsement (and emulation) of the Woolfian experiment — “We believed Virginia Woolf was right about everything” — and an arrow aimed at Stephen’s Victorian brain.

Woolf eventually makes her way into “After Sappho” (and livens it up a good deal — a splash of absinthe at a dinner party), but only after Schwartz’s women gather and disperse, flee forced marriages and find heterosexual relationships of convenience, ad nauseam. In their youth, they recoil at the stories they’ve been told: “When we were children we learned what happened to girls in fables: eaten, married, lost. Then came our bouts of classical education, imparting to us the fates of women in ancient literature: betrayed, raped, cast out, driven mad in tongueless grief.”

In adulthood, they gather to recite poetry in ivy-covered gardens, organize congresses for women’s rights, retreat to Greek islands, begin and abandon manifestos and manuscripts and push themselves into the arenas of life, especially art and sex, that men have doggedly guarded. One of the primary things they want is “a century less muffled in fabric.”

It’s hard to write succinctly about work that staggers in so many directions. Midway through the novel, I was reaching into a grab bag of vibes. Schwartz adores “cerulean and azure swaths” of “open sea,” the adjective “sibylline,” fabrics like “almond-coloured velvet” and “rough linen,” sunlight dappled by leaves. Sometimes her language is so overly lofty that I expected feathers to flutter out from between the pages.

The text swerves from breathy and adulatory to cutting and punky: “Marriage was fundamentally a humiliation of women”; “And will not the adequate critic of women be a woman?”; “We also longed for writing tables that were not in the kitchen.” Schwartz’s snappiest lines would fit on coffee mugs prized by middle-age moms as tokens of unexplored rebellion. Nevertheless, I nodded along.

The middle of “Sappho” goes soggy; the charm of its little eddies wears thin. (Please, hit me with a big wave.) That is, until World War I comes along. By the narrators’ telling, lesbians writ large entered a miniature golden age, “a sleek, exuberant step forward,” in the early 1910s. And then the men begin “their ‘Great War’: what a preposterous masculine fiction,” further proof that the world they run keeps women at their bloody mercy.

Yet the muddy killing fields of the Somme give the women something to define themselves against. (“Should the men of Europe be discontinued, they wondered?”) They hustle art away from the absent men and begin to make it all about themselves. “Short pieces taken from life… Enough lyric poetry. Not another still life with flowers. More portraits of us.” Is this the key to artistic equality? Self-portraiture?

Toward the novel’s last pages, a sketch of an unexpected (but historically accurate) character appears. Berthe Cleyrergue cooked and cleaned for Barney and Brooks in Villa Trait d’Union, the hyphen-shaped house they shared in the south of France. She observed their habits and neuroses: She “not only had all of her own lives to herself; she also saw straight through a dozen others.” Cleyrergue, the narrators exclaim, “taught us that we had been wrong about housekeepers.”

In 1980, Cleyrergue published a self-portrait of her own, documenting the exploits and personalities of the Sapphists she’d waited on and bonded with. When I can nab a copy in English, I’ll be curious to find out whether Cleyrergue ever bore any resentment toward her employers, who couldn’t cook and needed her to pour their glasses of Kir, dust their Parisian townhouse and pass around their sandwiches. The housekeepers and maids, cooks and kitchen girls made the artistic pursuits of other women possible.

Women replaced other women in the kitchen. Now they replace them in daycare centers. There is always an underclass of women, and I wonder about the Berthes who didn’t read Colette and couldn’t leave behind written documentation of their lives.

They may be the fragments missing from Schwartz’s homage to Sappho — this elusive, at times joyful and enveloping not-quite-novel. As Colette remarked about “La Naissance du Jour,” a book she designated by no other descriptor than “feminine,” “You may have sensed in this novel that the novel does not exist?” Is a novel what Schwartz wanted at all? A one-time-only performance piece in a grove of trees on Lesbos (followed by an orgy) might have suited her purposes better. Fleeting, immersive, surrounded by that dappled sunlight. I’d watch it.

Kelly’s work has been published in New York Magazine, Vogue, the New York Times Book Review and elsewhere.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.