Meet the people bringing us answers on the big bang, and their 13,000-pound helper

For some people, it’s a memoir or a work of fiction; others, their first company or app. For Scott Willoughby, it’s a more than 13,000-pound telescope that must unfold while in space and work in cryogenic temperatures.

“Webb is my middle child,” Willoughby said of the James Webb Space Telescope — his baby of 12 years — scheduled to launch Christmas Day from Kourou, French Guiana, on South America’s northern coast. It is a successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, which has observed distant stars and galaxies for more than 30 years but can’t see the first galaxies formed in the universe as Webb will be able to.

Willoughby, the telescope’s program manager at aerospace and defense company Northrop Grumman Corp., is part of a cadre of thousands of aerospace workers across NASA, Northrop and other firms who have devoted a huge part of their careers — some inadvertently — to this singular mission.

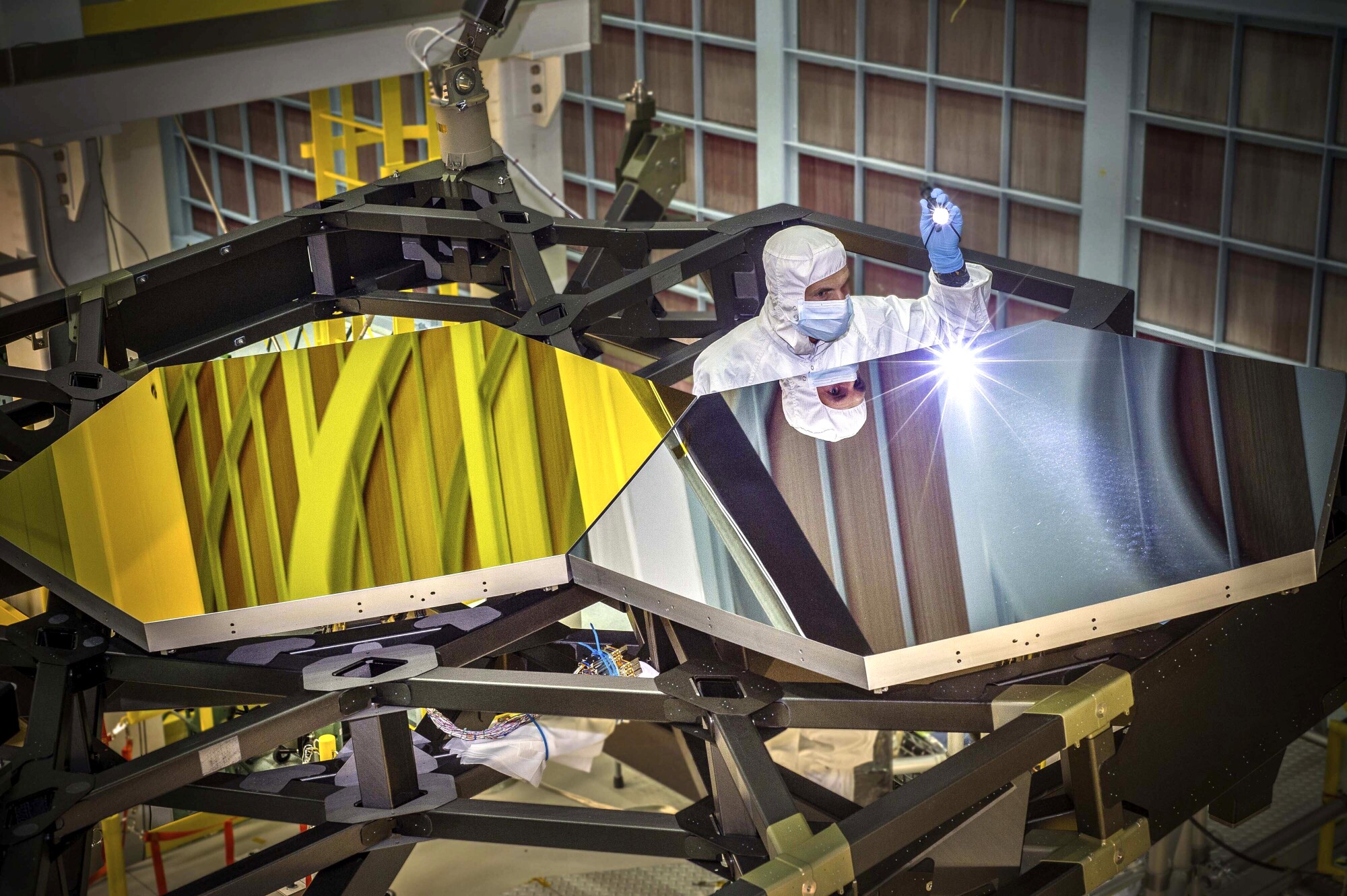

Webb optical engineer Larkin Carey examines two test mirror segments on a prototype of the Webb telescope at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

(Chris Gunn / NASA )

Their work spans nearly two decades, including about a decade of delays, numerous technical challenges and a hurricane that almost derailed a testing round. It culminates with the launch on Dec. 25, which Willoughby likened to seeing his two daughters leave home for college.

“When your kids leave home for that momentous occasion to start that adult life … you want them to do that and be successful, but you also want to follow them,” he said. “But you can’t.”

“I was only going to be on it for four to five years,” said Sandra Irish, NASA’s lead structures engineer for Webb. She has now worked on the program for 16 years.

Sandra Irish, NASA’s lead structures engineer for Webb.

(Chris Gunn / NASA)

Irish remembers crying as she watched the ship carrying the telescope, which was transported to the launch site in French Guiana from Seal Beach, pull into the harbor in October.

“Sometimes we like dull moments,” she said, reflecting on her years of work throughout Webb’s development and testing — before adding that there weren’t any.

The Webb telescope is designed to look for faint infrared light — the first light to streak across the dark universe 13.8 billion years ago — that will allow scientists to understand more about the origins of the universe. It has a mirror nearly three times larger than that of the Hubble Space Telescope and a five-layer sun shield unlike anything ever built before.

“There wasn’t anything else out there that I could look at and improve on,” said Jim Flynn, director of vehicle engineering for the telescope at Northrop Grumman, who has been on the program for 17 years. The sun shield, made of a film material called Kapton that’s covered in a special coating, helps keep the telescope cool.

Much of the work on the telescope was groundbreaking, including the production of 18 hexagonal, lightweight mirrors and ensuring that Webb can function fully at cryogenic temperatures. Over the years, costs ballooned to $10 billion (earlier estimates ranged from $2 billion to $8 billion), and development setbacks delayed the launch date.

“I’m the dinosaur,” said Charlie Atkinson, who has the longest tenure on Webb at Northrop Grumman: He started on the program in 1998 and now serves as its chief engineer.

Webb’s development lifespan has traced the trajectory of the lives that merged, took new paths and blossomed as its longest-serving creators built it up, year in and year out.

Careers lighted up. Friendships formed. Kids grew up and went to college, and still the telescope was in the making.

Atkinson’s twin daughters were born in 2000, while he was working on the proposal for Webb. Co-workers at the time still remember when he’d say, “I gotta go home, it’s bath night.”

In May, Atkinson’s daughters will graduate from college.

Lee Feinberg, optical telescope element manager for the Webb program, stands in the clean room in front of the telescope mirror. The Webb launches after about a decade of delays and cost overruns.

(Chris Gunn / NASA)

“I sometimes tell people it feels like we sprinted a marathon,” said Lee Feinberg, optical telescope element manager at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

Over the course of his 20 years on the program, Feinberg was in and out of several music groups, including a tribute group called the Allman Others Band.

Like any all-consuming endeavor, work on the Webb came with compromise and sacrifice.

Feinberg would often take his children to school, get on a plane for work, return home around 2 a.m. and then take the kids to school again the next day. “A lot of it was sheer exhaustion,” he said.

“It takes a toll on you,” said Atkinson, who traveled frequently during his years on the program visiting subcontractors and other NASA facilities in places such as Colorado, Utah, Alabama and Texas. That left his wife with much of the heavy lifting at home.

Irish, who on a recent video call wore a dark blue shirt emblazoned with a white outline of the telescope — one of many in her Webb-branded clothing collection — keeps a photo of her children and now daughter-in-law, posing in front of the telescope, as her desktop image.

The photo was taken just before the telescope was shipped to Johnson Space Center in Houston for more testing, about four years from final transport to the launch site. It was a special moment to share her work with her family, especially after long stretches away from them, including working holidays when the telescope was being prepared and undergoing mechanical testing in 2016 and 2017.

“You have to have dedicated and supportive family,” she said. “Otherwise, I don’t think you can do it.”

For Sarah Willoughby, work on the telescope was special because, unlike many of her previous projects, it wasn’t classified, and she could tell her loved ones all about how it was progressing. She and Scott Willoughby married after working together on the project.

“There’s a lot of things we work on that you can’t share,” said Sarah, vice president of overhead persistent infrared and geospatial systems at Northrop Grumman.

The most difficult challenge of her career, she said, was figuring out how to put Webb “on a diet” so it could meet the weight requirements of the Ariane 5 rocket, which will carry the telescope to space.

As deputy spacecraft manager at the time, she worked with teams spanning all the telescope’s sections to whittle away at its mass so it would be ready and able to launch.

Rob Pattishall, director of integration and test at Northrop Grumman, started working on the Webb in 2004. He is pictured here at Northrop’s Space Park facility in Redondo Beach.

(Northrop Grumman)

Like any aging Californian, Webb saw its share of natural disasters over the course of its development. Irish has a file on her desktop labeled “earthquake data” that chronicles temblors the telescope withstood while parked at Northrop Grumman’s Space Park facility in Redondo Beach for final assembly.

By far one of the biggest tests came in 2017, when Hurricane Harvey hit Houston just as the integrated telescope and its instruments were being tested in a chamber at Johnson Space Center that was modified to accommodate testing in cryogenic temperatures.

Once the test started, its super-cold temperatures had to be maintained because it would take too long to warm back up to normal temperatures. So as the rain poured down, the chamber testing had to continue.

Workers with high-clearance vehicles drove to rescue colleagues who were stranded. Others went to the grocery store to get food and water. Air mattresses were brought in for those stuck on site or who had damaged homes.

“It was a very challenging week,” Feinberg said. “That’s one of the reasons I feel pretty good about how we’re going to be able to handle the efforts in front of us. This team has proven resilient over the years.”

The moment that approaches — the finish line, in some ways — feels, for many, bittersweet.

“I don’t know what the words are,” Rob Pattishall, director of integration and test for the telescope at Northrop Grumman. “Surreal. I see it happening, I know in a couple of weeks, I won’t have [the telescope] anymore,” he said by telephone call from Kourou last week. “But how can that be possible?”

Pattishall’s eldest child was a year old when he first started working on the telescope in 2004. Last week, she came home from her first semester at college.

He’s looking forward to spending the final days of the year with her on Earth, while, far away, Webb embarks on its search for distant light in space.

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.